Preface

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's primary objective is to contribute to the greatest possible values for society from the oil and gas activities through efficient and prudent resource management, where due consideration is given to health, the environment, safety, as well as other users of the ocean.

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate has had responsibility of all of this for more than 50 years. Today’s world is vastly different from where we started out. When we changed our name to the Norwegian Offshore Directorate on 1 January 2024 it was, in part, a reflection of the new endeavours and challenges we have taken on, not least those related to CO2 storage and seabed minerals.

Let’s focus on the future. The vast resources we still have on the NCS will help supply the energy the world needs in the years to come. In fact, Norwegian oil and gas can be a key factor in addressing very real challenges, such as secure and stable energy for Europe. At the same time, interesting new concepts such as seabed minerals and CO2 storage could possibly be developed into profitable new industries, creating enormous value and bringing important contributions to the energy transition.

A long-term perspective is one of the essential building blocks in our resource management. This report illustrates opportunities, and outlines what’s needed to make sure our shared resources continue to generate value for the broader society. We need to be aware of the significant uncertainty linked to long-term value creation and ongoing development. These are broad considerations in every sense of the word – the geopolitical situation, climate policy in the EU and worldwide, developments in the oil and gas markets and in more concrete terms, evolving technology and overall costs.

Keeping all of this in mind, our long-term assessments need to reflect this uncertainty, while standing up to scrutiny in a rapidly changing world.

Our guiding objective is to promote good choices as we stake out a course to create more value in the future. We hope this report can facilitate better dialogue, increase understanding of both challenges and opportunities on the NCS, and can thereby unlock the best path forward. Working together, for the benefit of all.

Kjersti Dahle

Director technology, analyses and coexistence

It is with great sadness that we note the passing of two of our colleagues over the past year, Dag Helliksen and Kirsti Veggeland. We want to honour their legacy by dedicating this report to them.

Summary

However, realisation of these resources requires an ambitious path that will need careful consideration and hard work. Forecasts point to an expected decline in overall production on the NCS after 2025. Smart exploration and robust investments will be needed to curb this decline. If investments falter, the stage will be set for a rapid dismantling of our petroleum sector.

Extraction of seabed minerals, CO2 storage and offshore wind could become profitable new industries; assuming they prove themselves cost-effective, and that they can stand up to competition with alternatives. These new industries are also well-suited to reinforce and benefit from already established value chains and the many lessons already learnt.

Oil and gas going forward to 2050

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate seeks to provide data and analyses to support decision making for developing the NCS. The preparation and development of alternative scenarios for total oil and gas production up to 2050 is a key part of these efforts. All three scenarios presented here do indeed indicate production decline, but with very different trajectories.

What this production decline entails will ultimately come down to a number of factors including how much exploration is undertaken and how quickly, as well as the pace of technological progress and development. It’s worth noting that this generally accepted production decline is in line with the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

In the basic scenario multiple discoveries are made and brought on stream, accompanied by investments aimed at increasing recovery from existing fields. Despite this, resource growth will not be sufficient to offset the overall gradual decline, due to diminishing production from the major, mature fields.

In contrast, the high scenario will mean vigorous exploration, many discoveries, rapid technological development and eager investors willing to take a chance on the NCS, bolster production and thus help mitigate shrinking government revenues up to 2050.

Finally, a look at the low scenario reveals sluggish exploration activity and investment, thus leading to rapid dismantling of the petroleum sector and the inevitable significant drop in revenue for the government.

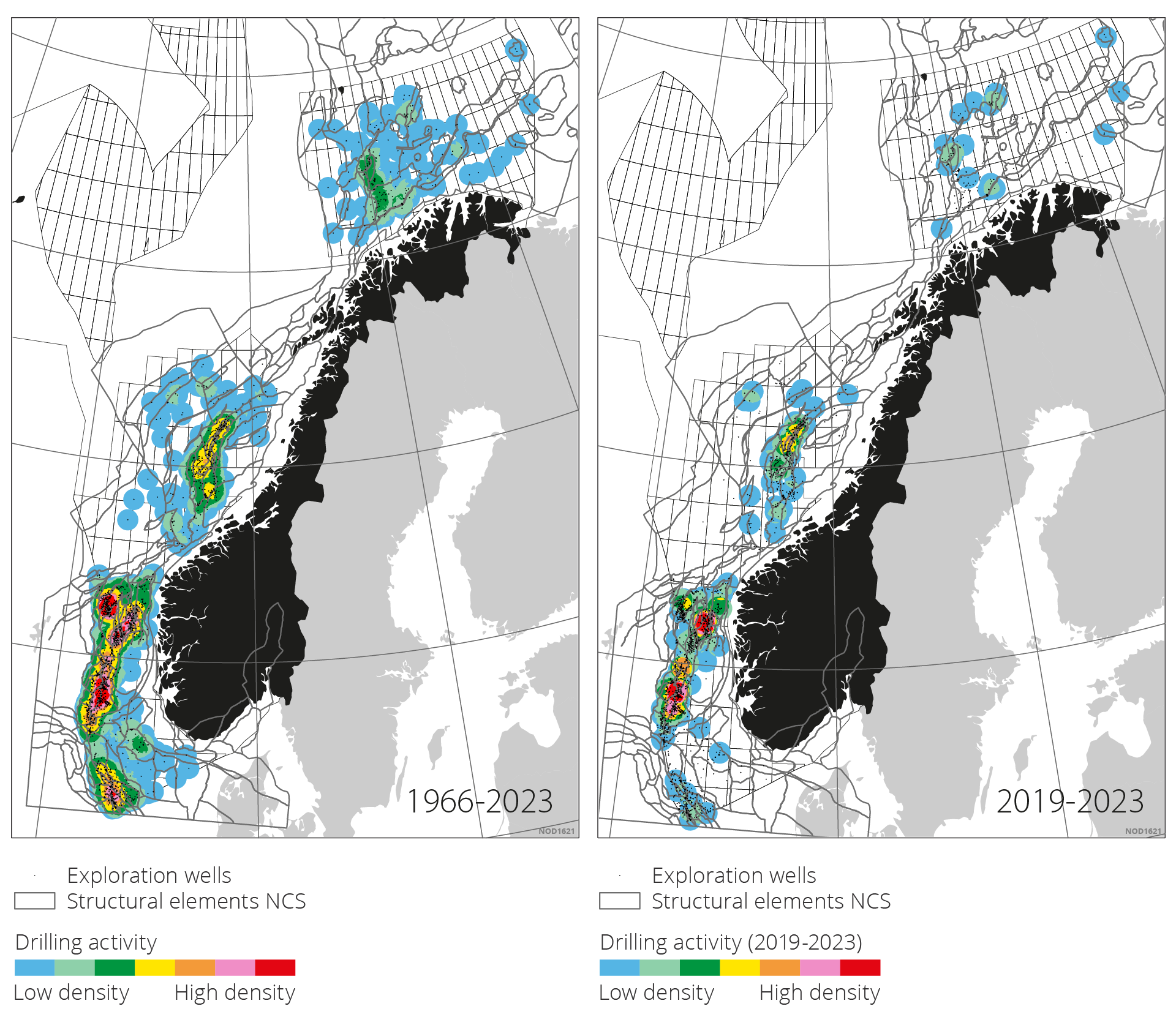

Substantial resources still in the ground

The NCS still contains large undiscovered oil and gas resources. To secure our objective to maximise the value of the resources on the shelf, the resources first need to be found. Finding these resources will mean more exploration, both in more frontier areas and close to the extensive infrastructure already in place.

There are interesting opportunities when it comes to undiscovered resources, both in familiar and less-explored areas. More extensive and detailed information, better data coverage, new work methods and pioneering technology open the door for fresh approaches in exploration, which could result in more profitable discoveries in the time ahead.

The ability to consistently incorporate new learning and the will to seek new knowledge and develop new technology are also important contributors that can enable us to unlock the values in challenging reservoirs, and also in smaller discoveries. And development of advanced methods to improve recovery from existing fields represent a very significant upside potential.

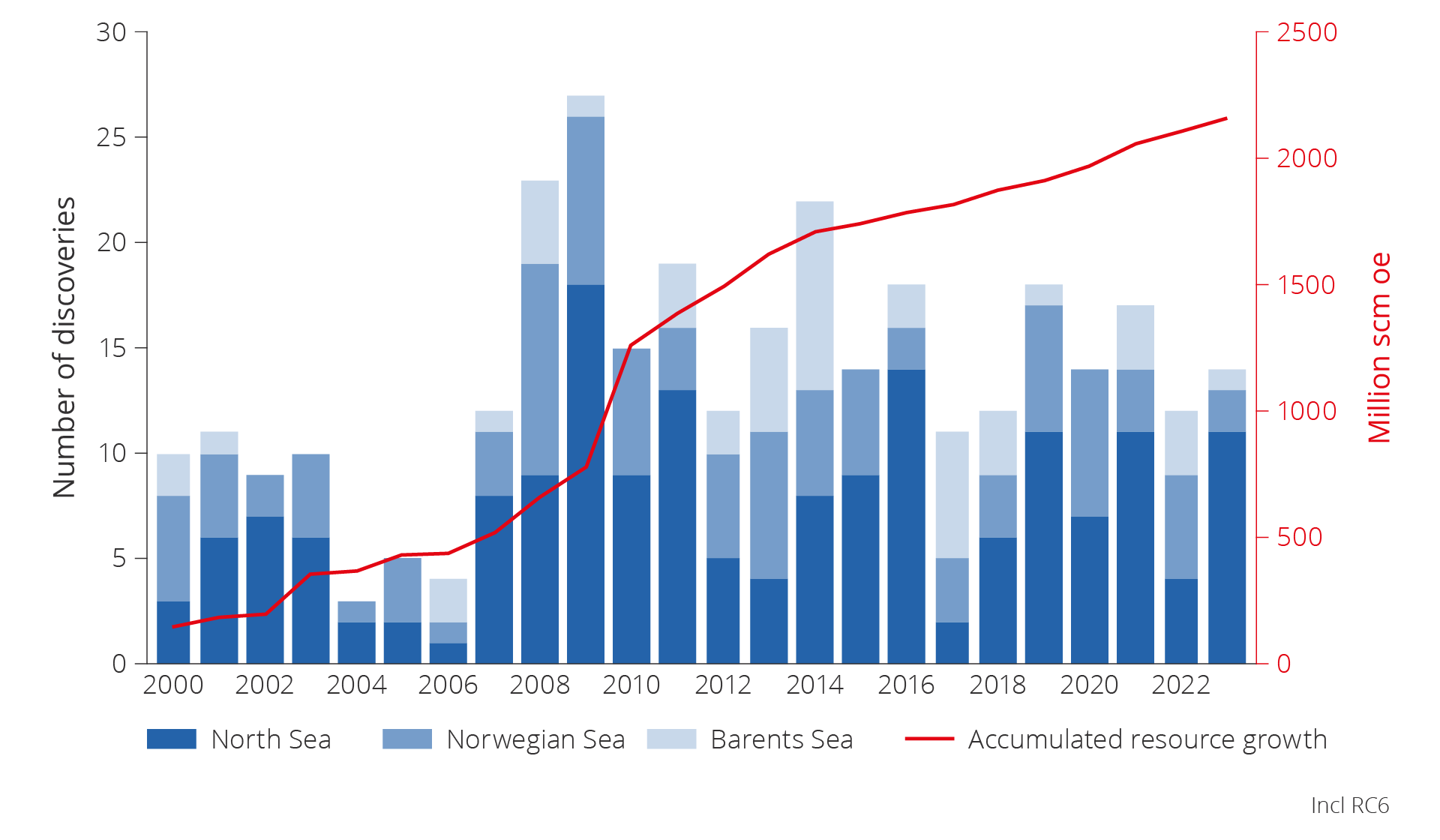

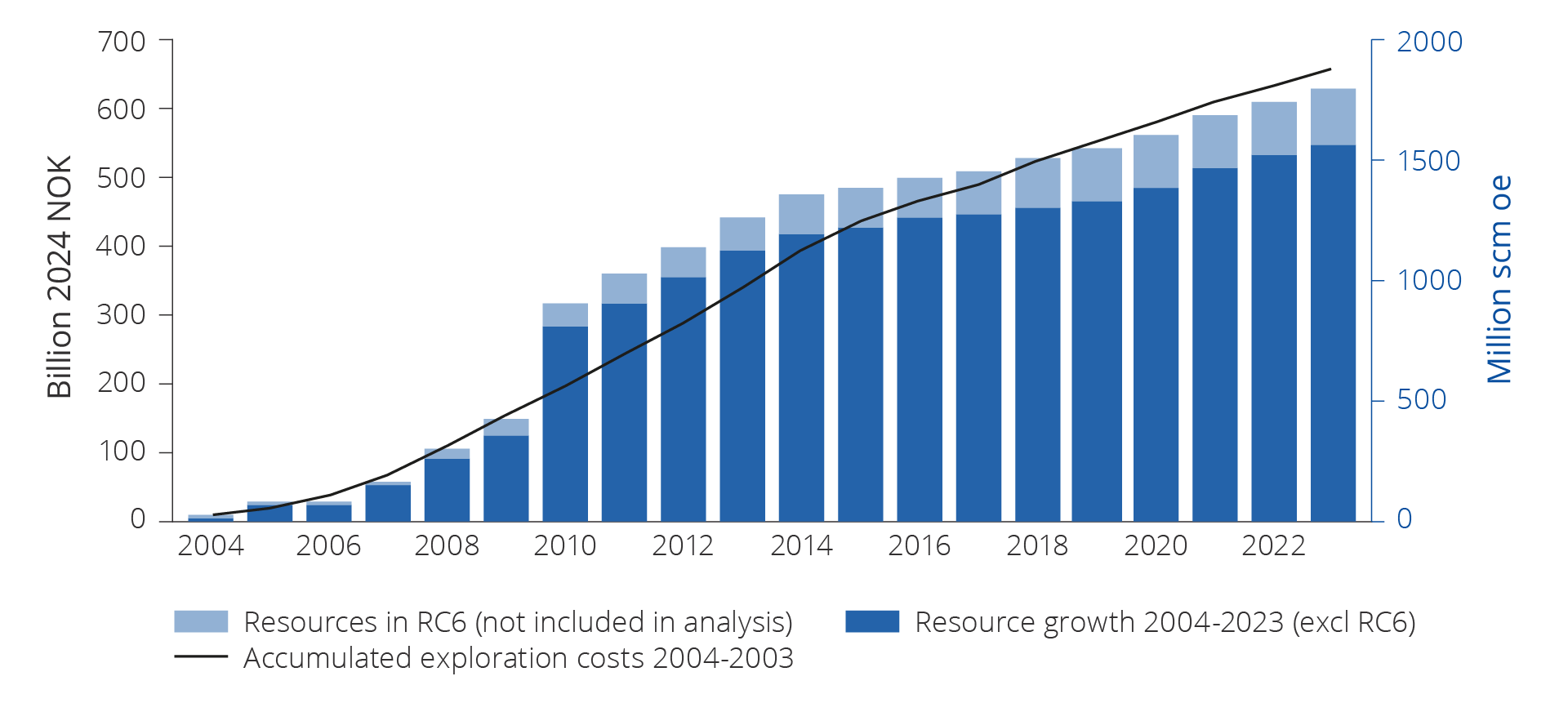

Profitable exploration

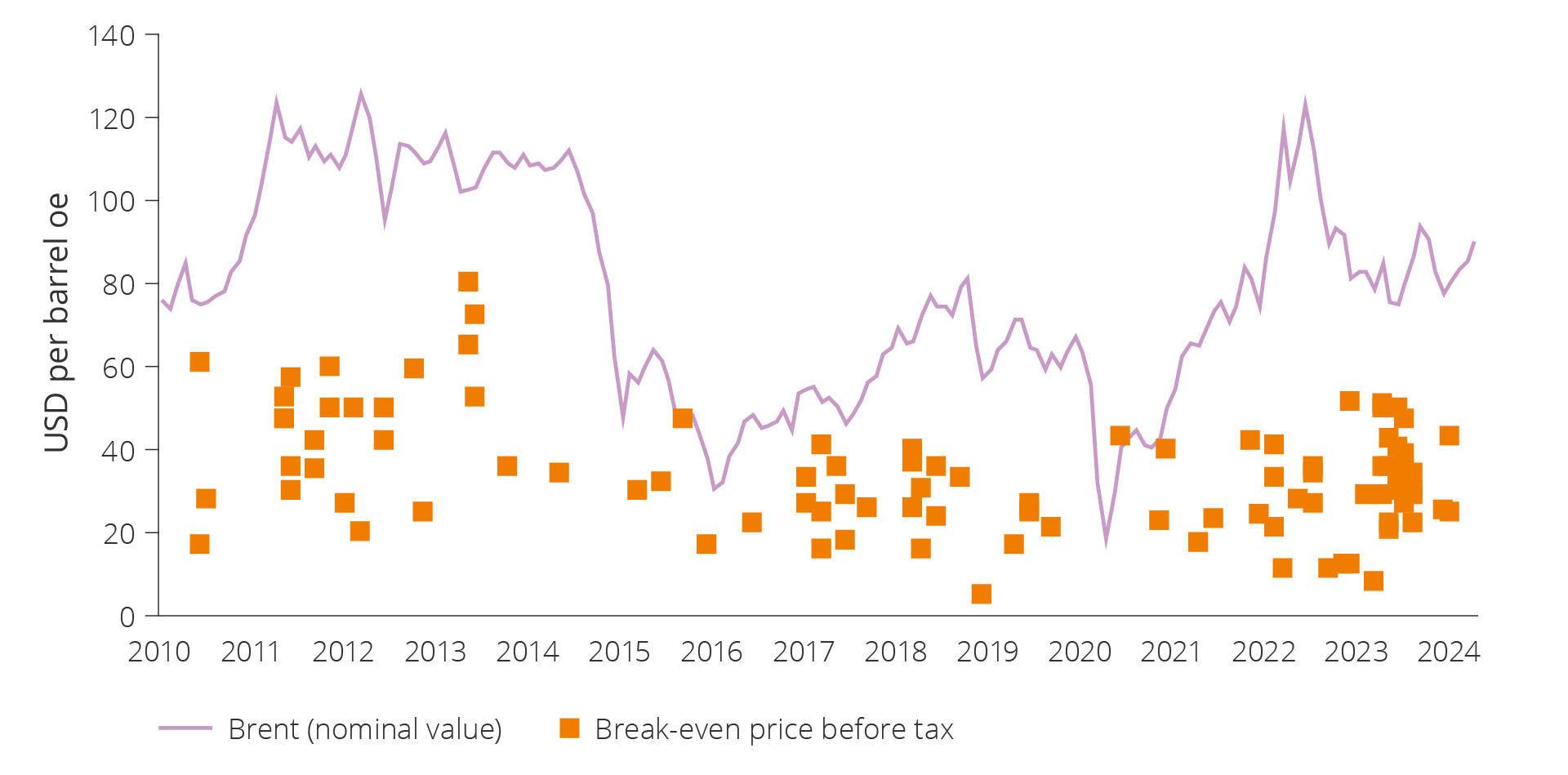

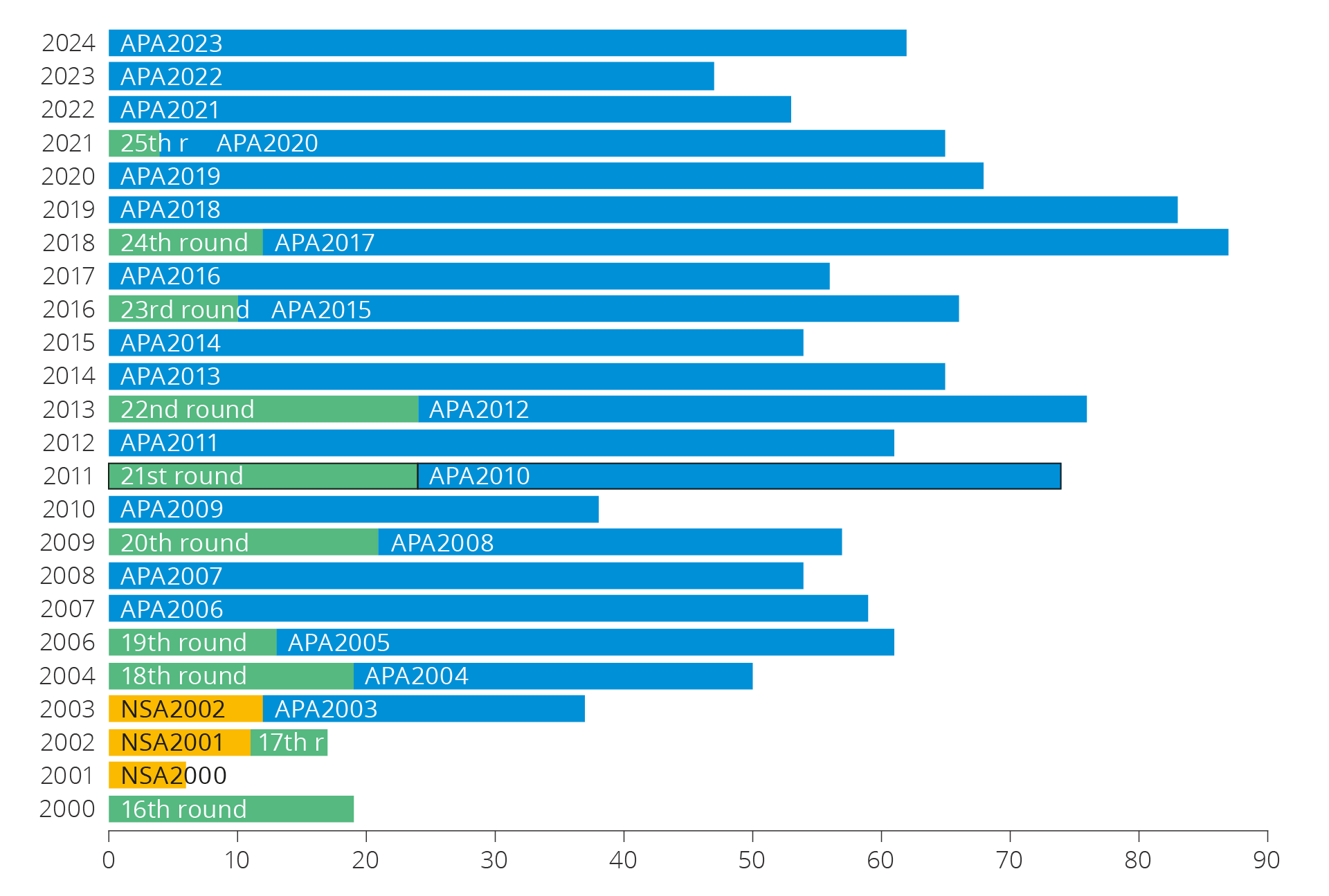

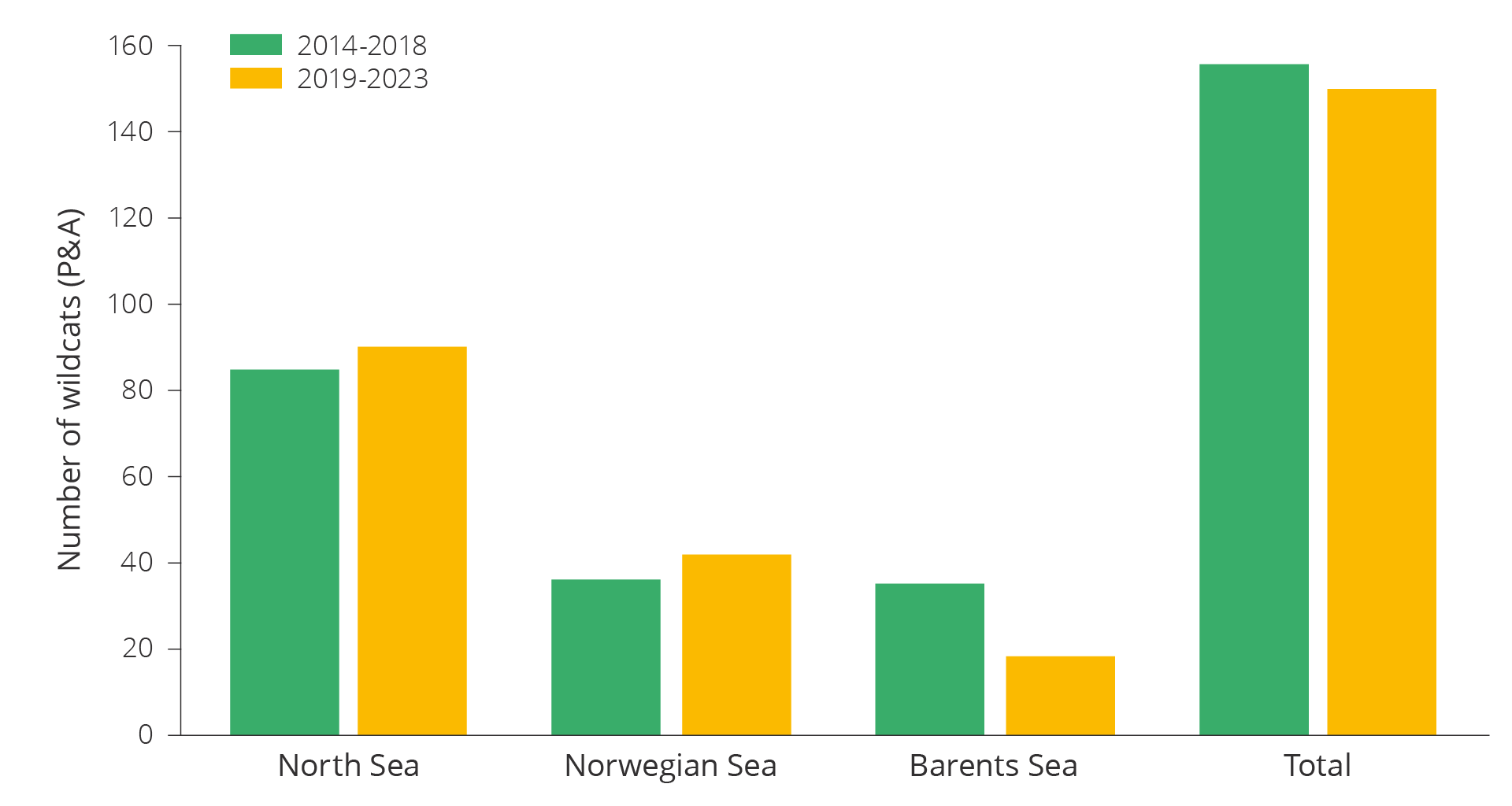

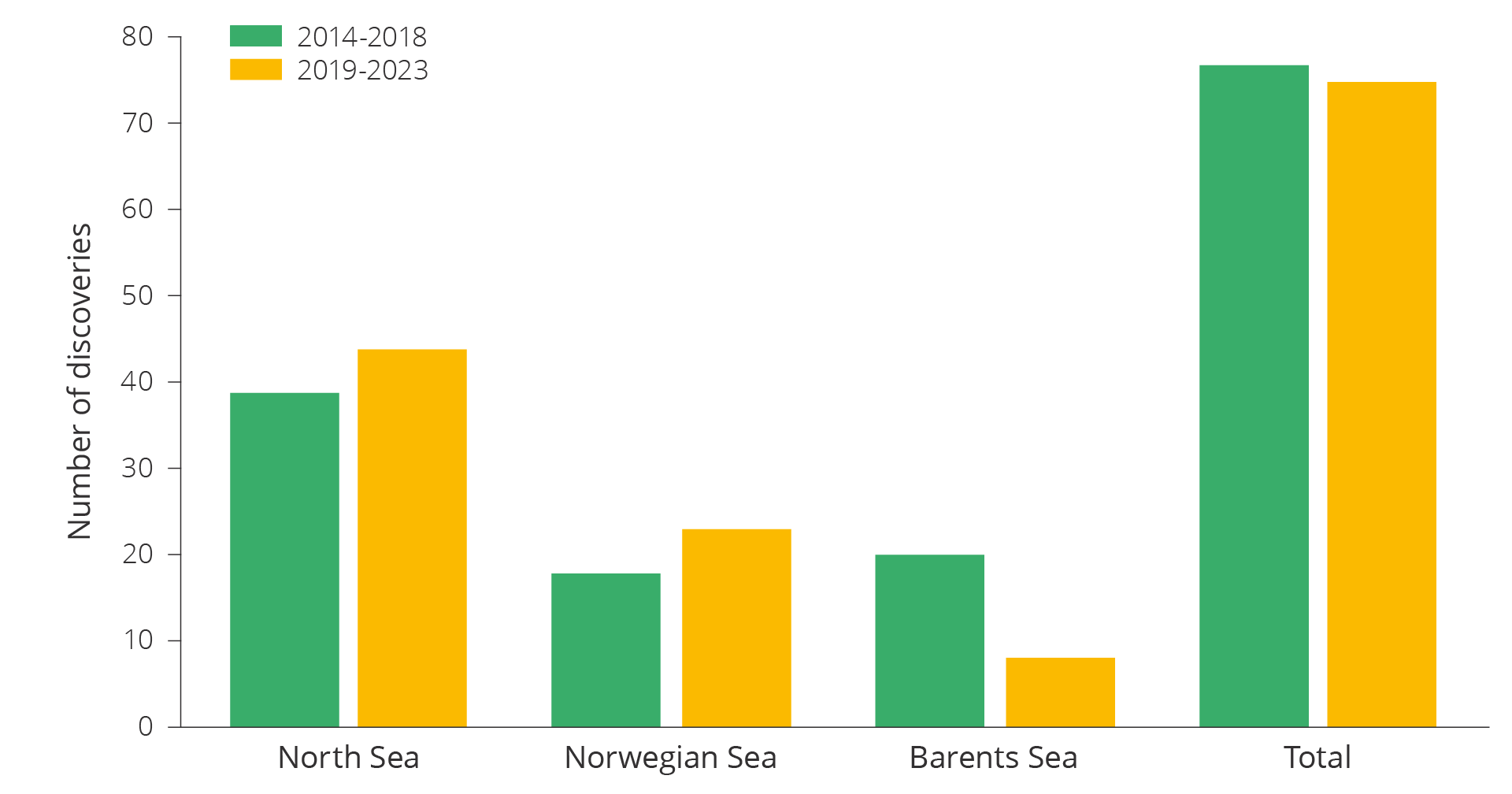

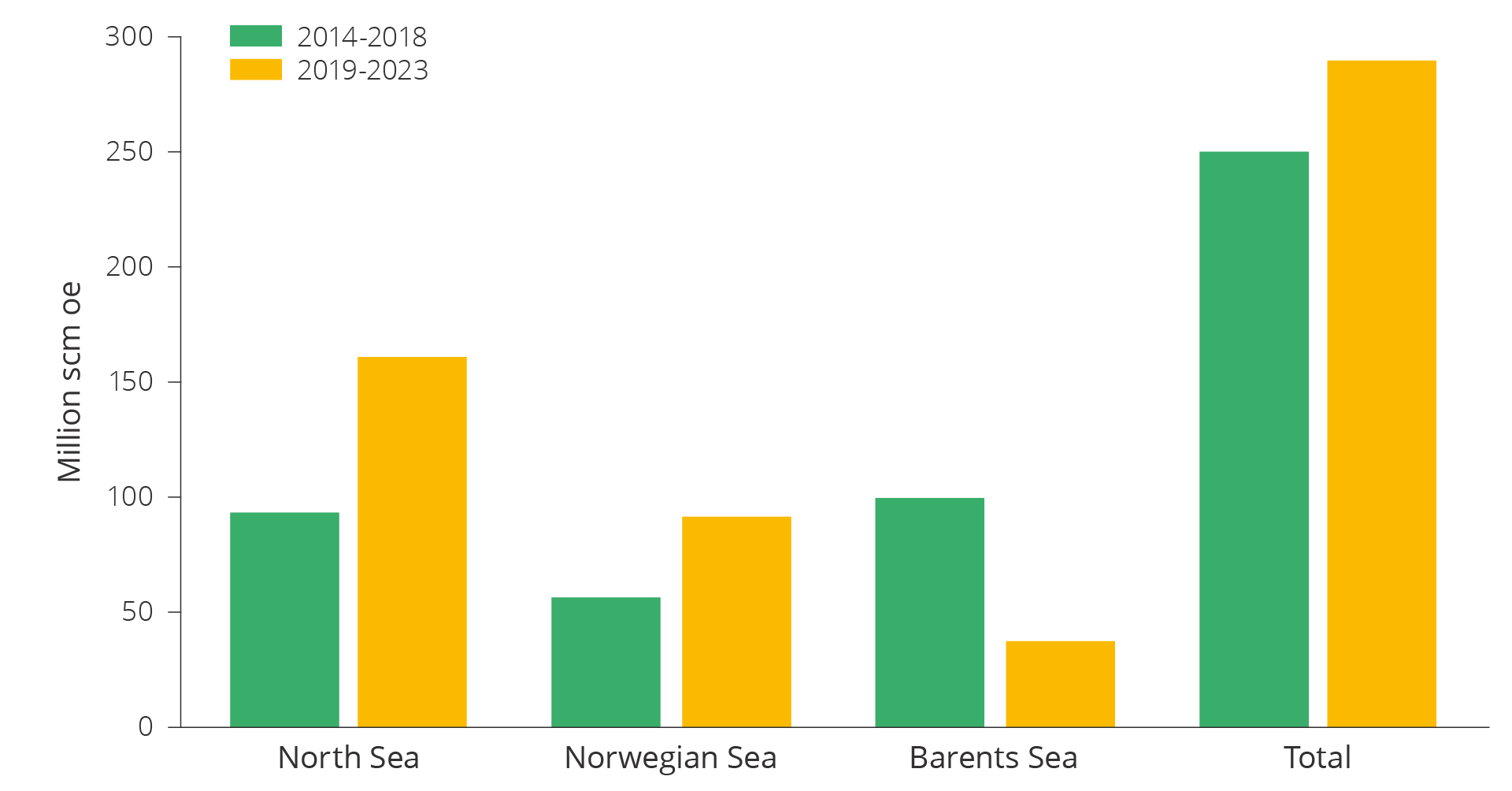

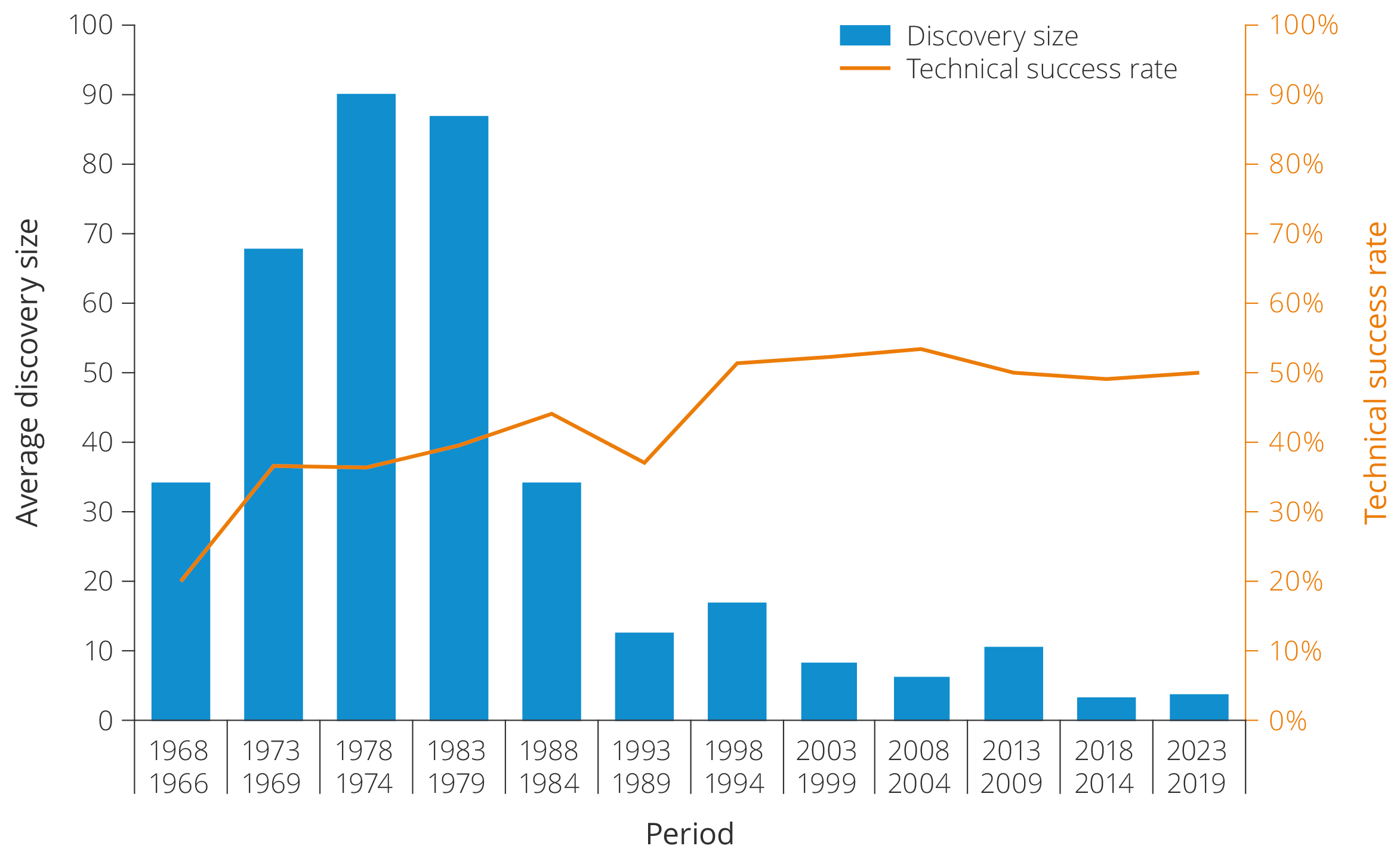

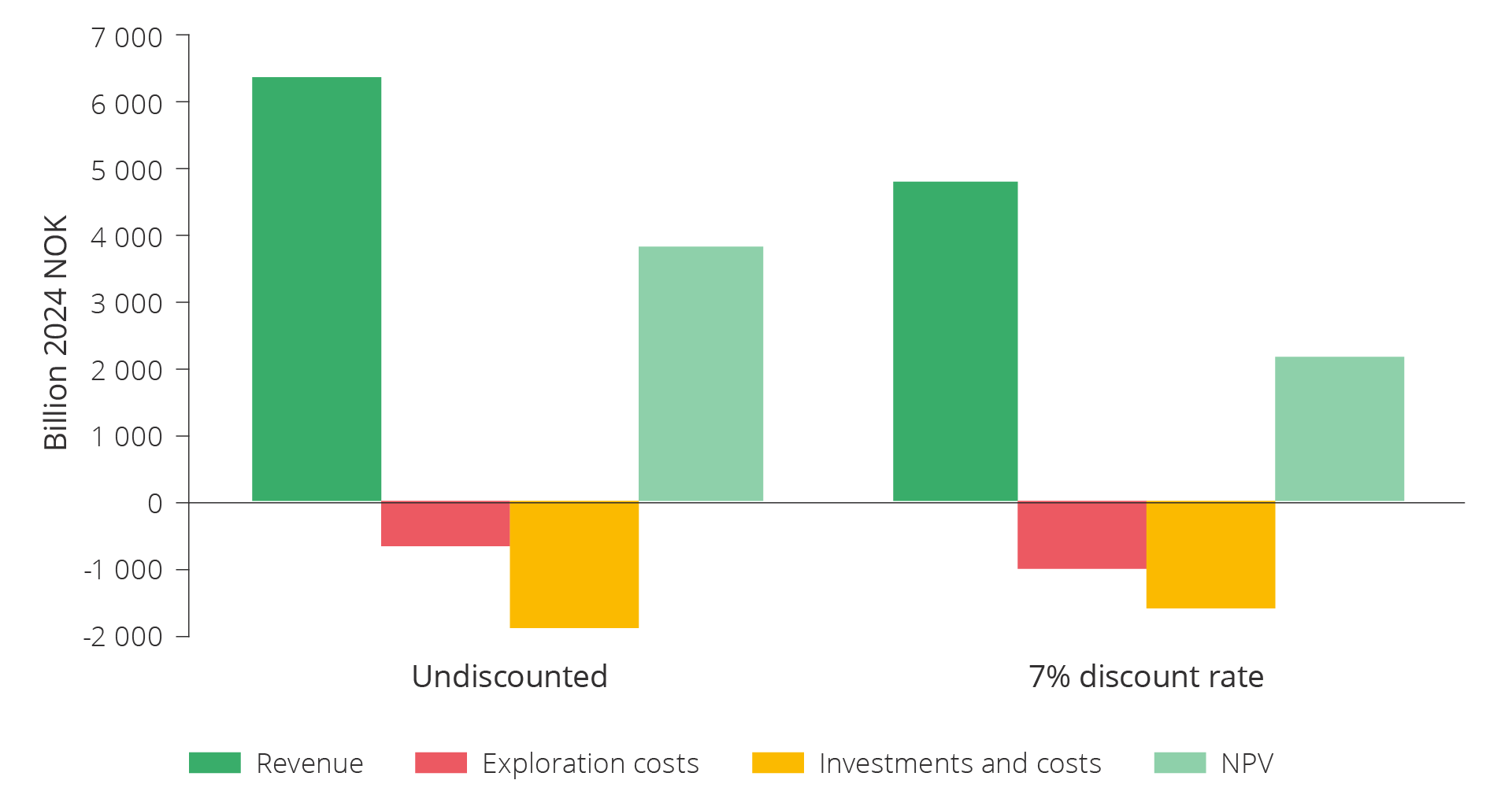

There is no question that exploration is a profitable activity. The Norwegian Offshore Directorate conducted an analysis of exploration activity over the past 20 years which confirmed that exploration for oil and gas on the NCS helps deliver incredible value for the broader community.

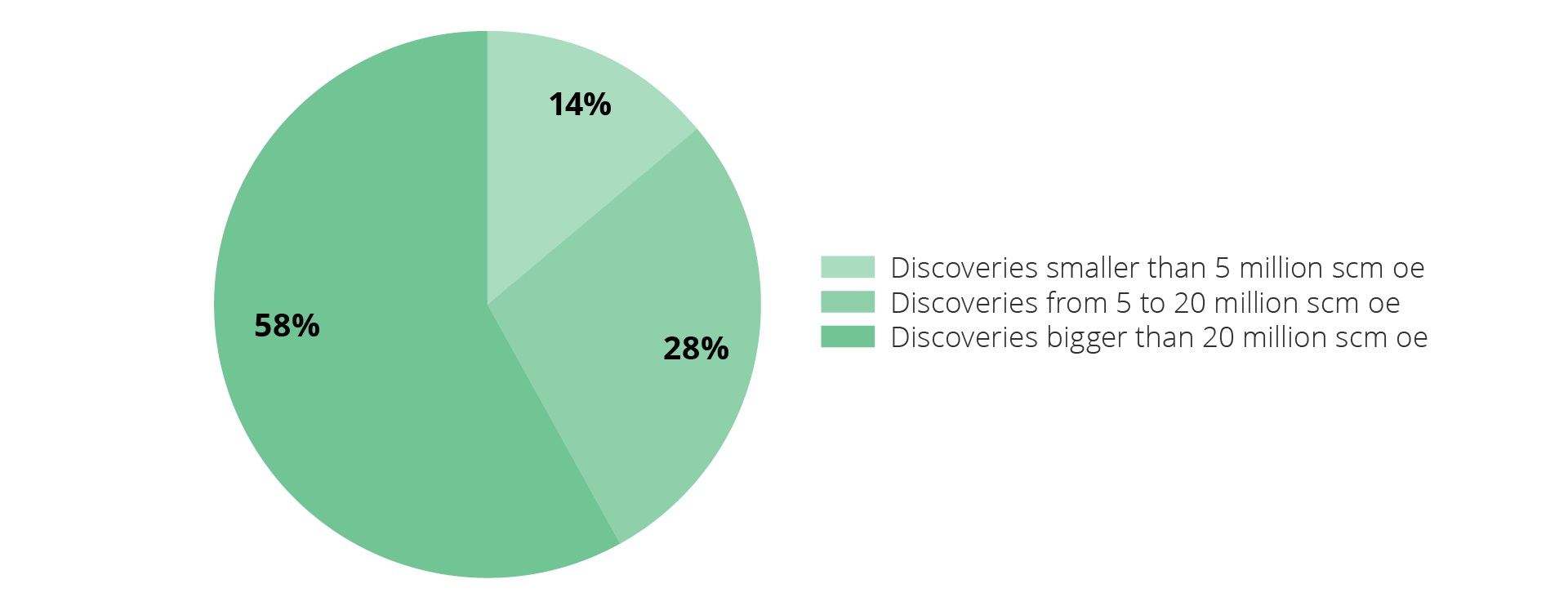

In concrete terms, we’re talking about more than 2000 billion Norwegian kroner (net present value). In fact, discoveries have generated value amounting to more than three times the costs devoted to exploration during this period.

Discoveries that have resulted in actual production have already offset total costs for all exploration investments in this period. The current track record shows a respectable 50 of 190 discoveries achieving development and production. That leaves around three-quarters of the discovered resources still waiting. The investments already made will continue to generate revenue as more discoveries come on stream.

Another takeaway from the analysis is that, while larger discoveries contribute most to value creation, a combination of many small discoveries can also deliver very substantial value across the board.

Robust activity

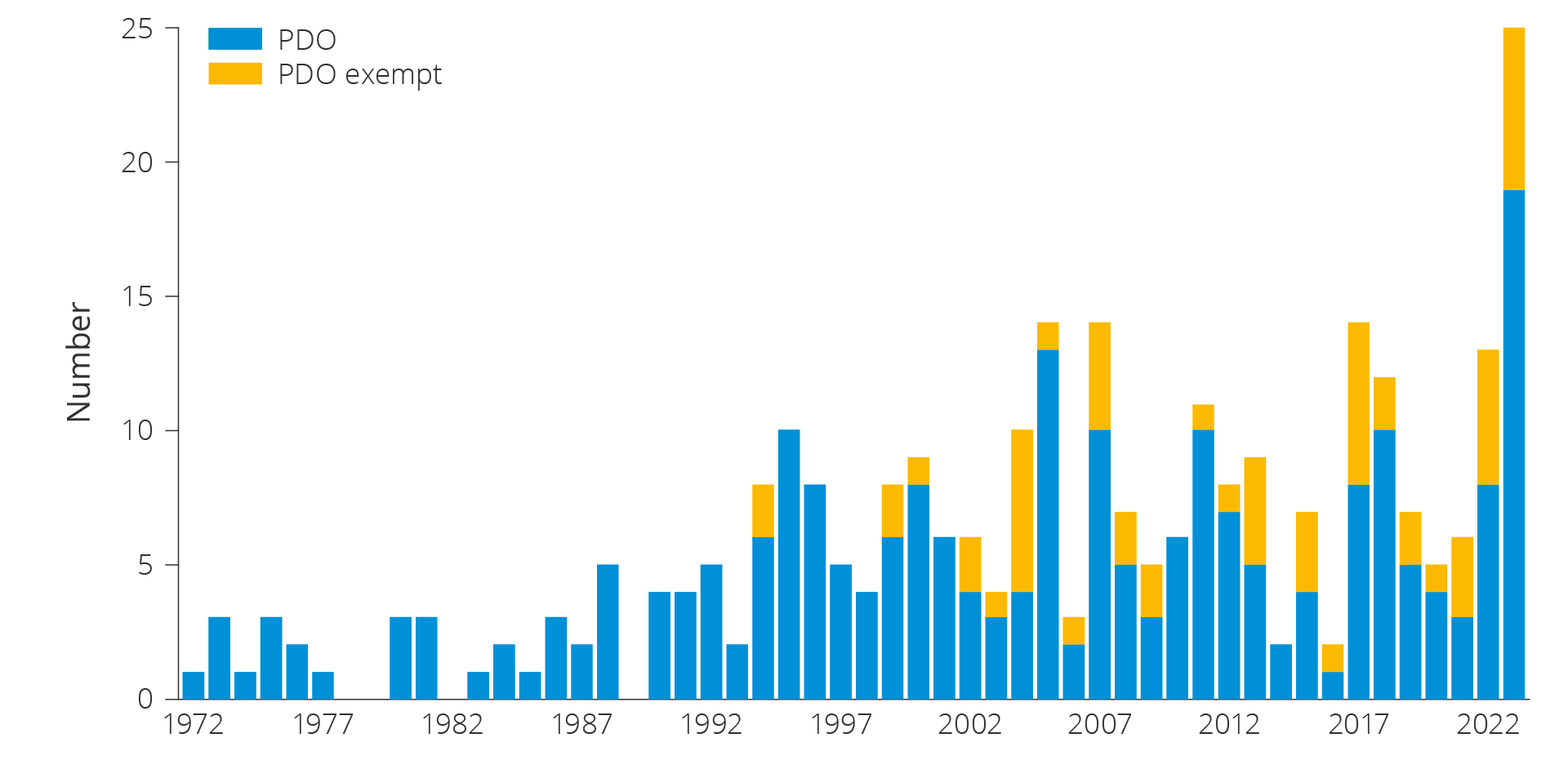

A large number of PDOs (plans for development and operation) were submitted to the Ministry of Energy in 2022, all of which secured approval during the course of 2023. The spike in PDO submissions can mainly be attributed to the temporary changes in petroleum taxation introduced in 2020.

These changes have helped facilitate more developments, paving the way for a swifter path from planning to production. The Directorate’s analysis confirms that this has had a substantial positive impact on value creation.

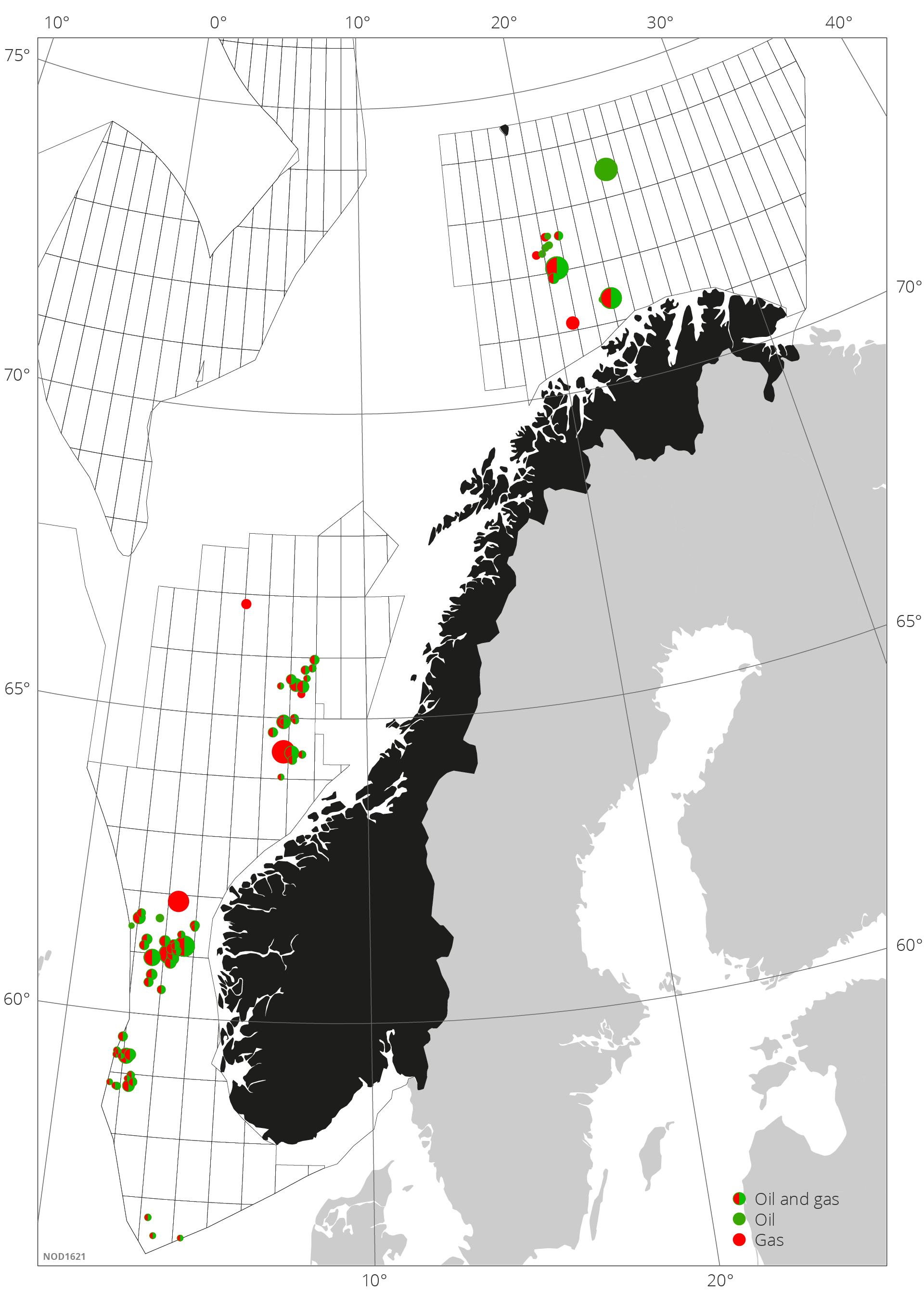

Increased gas export capacity from the Barents Sea

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate’s projections indicate that nearly two-thirds of all undiscovered resources are in the Barents Sea. The challenge here is that, without a firmer commitment to increase gas export capacity, these gas resources and values could remain locked in the subsurface for quite some time.

Designing and building more extensive infrastructure in and around this area is a prerequisite for developing oil and gas resources already proven. An increase in gas export capacity would also mean incentives for further gas exploration. There are a number of existing opportunities in the Barents Sea worthy of more detailed study.

Foundation for long-term production

What are Norway’s advantages? Vast remaining resources, well-developed infrastructure, low operating costs and stable, practical overall framework conditions. This tried and tested model suggests that Norway has what it takes to continue in its role as a competitive producer and exporter of oil and gas for the foreseeable future.

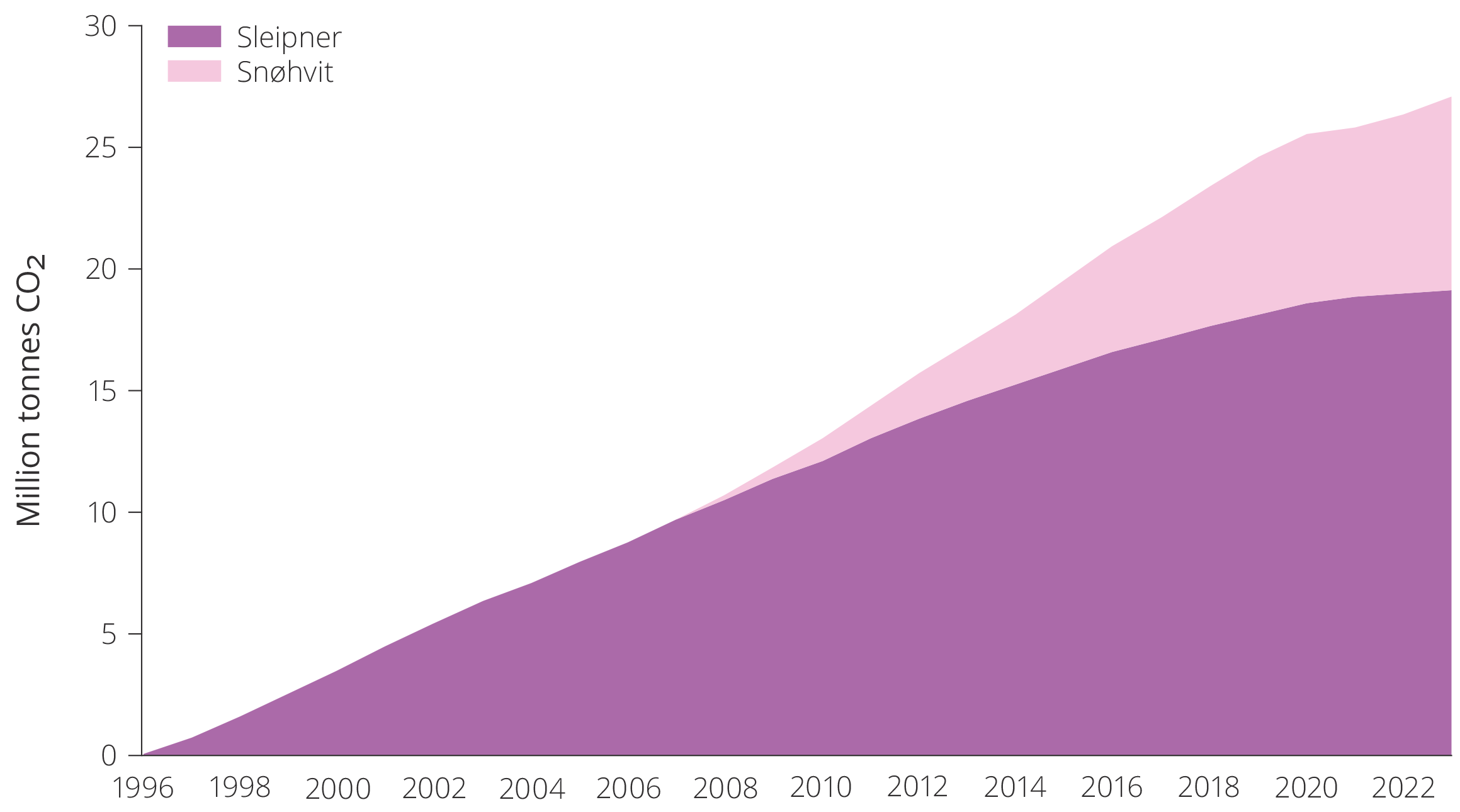

But there’s more. Huge volumes of CO2 resulting from power generation and industrial activity in Norway and Europe can be stored in the subsurface on the NCS. This presents a range of opportunities which are generating substantial interest and activity.

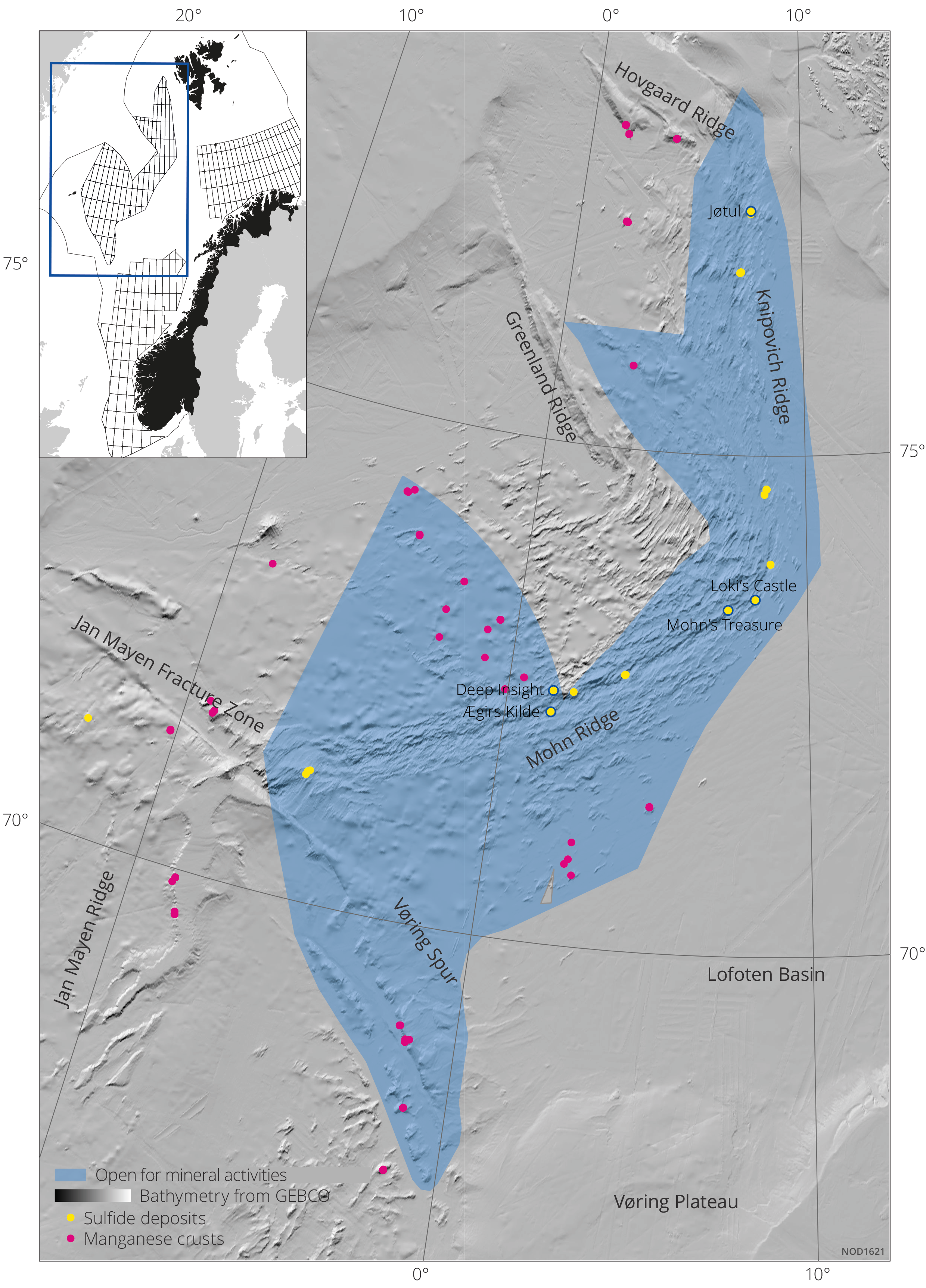

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate has also mapped significant mineral resources on the seabed which could contribute to the global supply of critical minerals. The first licensing round is expected to open in 2024. Time will tell whether this could prove to be an important new industry that can create value for Norway as a whole.

Background

In this chapter:

- Uncertain global landscape

- The world needs oil and gas

- The Norwegian continental shelf is competitive

- Need for considerable investments moving forward

- New industries on the shelf

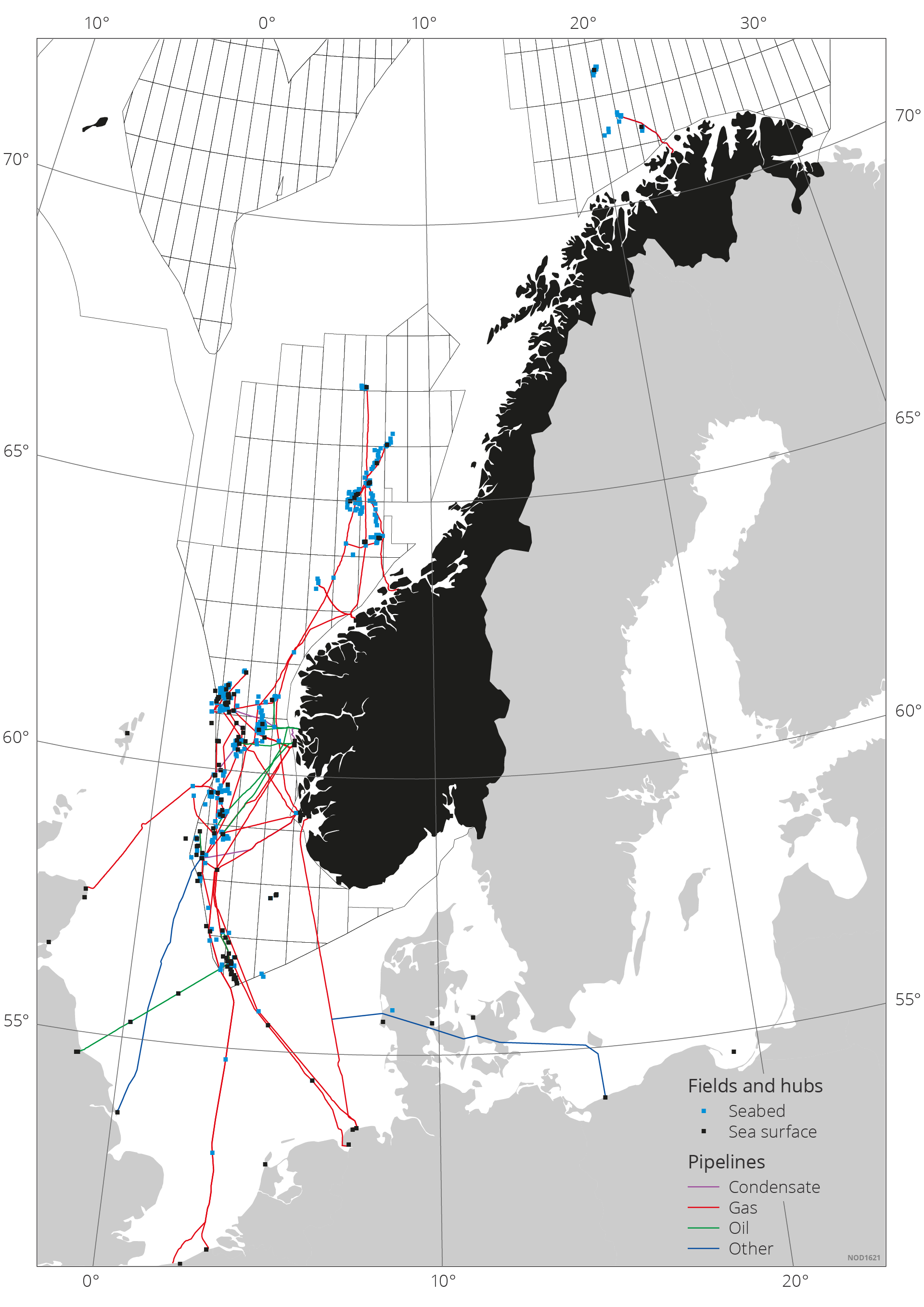

The Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) has supplied Europe with oil and natural gas for more than 50 years. The efforts invested on the NCS have brought secure and stable energy to Europe, while simultaneously providing Norway with vast revenues. Norway is currently the largest producer of oil and gas in Europe.

Uncertain global landscape

The global population, as well as business and industry, need energy to function and to reach the UN's Sustainable Development Goals(1). Uninterrupted access to sufficient energy at acceptable prices is a prerequisite for sustainable economic progress and social welfare development. Procuring enough energy for a growing global population poses however a significant challenge.

With the exception of brief periods during economic crises, global energy consumption has increased year-on-year. Particularly rapid energy consumption spikes have been observed in important regions of the global economy during periods of high economic growth. Whereas developing countries are especially vulnerable in terms of underlying energy needs. Their growing populations need energy to meet basic needs and achieve their desire for a better life and higher standard of living.

Significant and rapid emission cuts, in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, will require an energy transition involving extensive changes in global energy supply. Among other things, this includes energy efficiency measures, more development of renewable energy alongside new low-emission solutions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS). The energy and climate challenges the world is facing will need a range of simultaneous solutions.

Coal, oil and gas dominate the current, complex global energy system. This dependence leads to substantial greenhouse gas emissions, which have serious and irreversible consequences.

These energy sources have consistently accounted for around 80 per cent of the overall energy supply. More prevalent use of new energy sources has made significant additional contributions to existing sources, a factor which has been crucial in addressing rising energy needs. Furthermore, there is still extensive use of traditional biomass, with the associated challenges this brings for many low-income countries.

It will be challenging to implement the necessary transition of global energy systems quickly and the pace is uncertain. An energy system that is consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement will however be entirely different from the system in place today. Renewable energy will be an important part of the solution, but as of today, it is difficult to predict which combination of technologies and solutions will prevail and succeed. Particularly when other societal considerations are also taken into account. The uncertainty surrounding future developments has therefore a direct impact on the need for the different energy sources.

Both commercial and political reasons have led various business sectors in the West to limit their investments in fossil energy, which to a lesser extent, are also being seen in other parts of the world. Many western countries have introduced measures to improve their energy security in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, several major oil companies have tweaked their business strategies to reflect a more balanced split between oil and gas activities on one side and renewable energy on the other.

While European gas prices so far in 2024 remain far lower than the record prices in 2022 and the last half of 2021, prices are still high in a historical and global perspective. In Europe, the lapse of Russian gas deliveries has led to a significant increase in imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). LNG represents a link, both physically and in terms of price, between the gas markets in Asia, Europe and the US.

The global balance and competition in the LNG market is one of the most important drivers behind the evolution of European gas prices. Developing countries that import LNG are most vulnerable to the impact of high gas prices, but even in Europe, this is a challenging price level for households, businesses and energy-intensive industry.

The world needs oil and gas

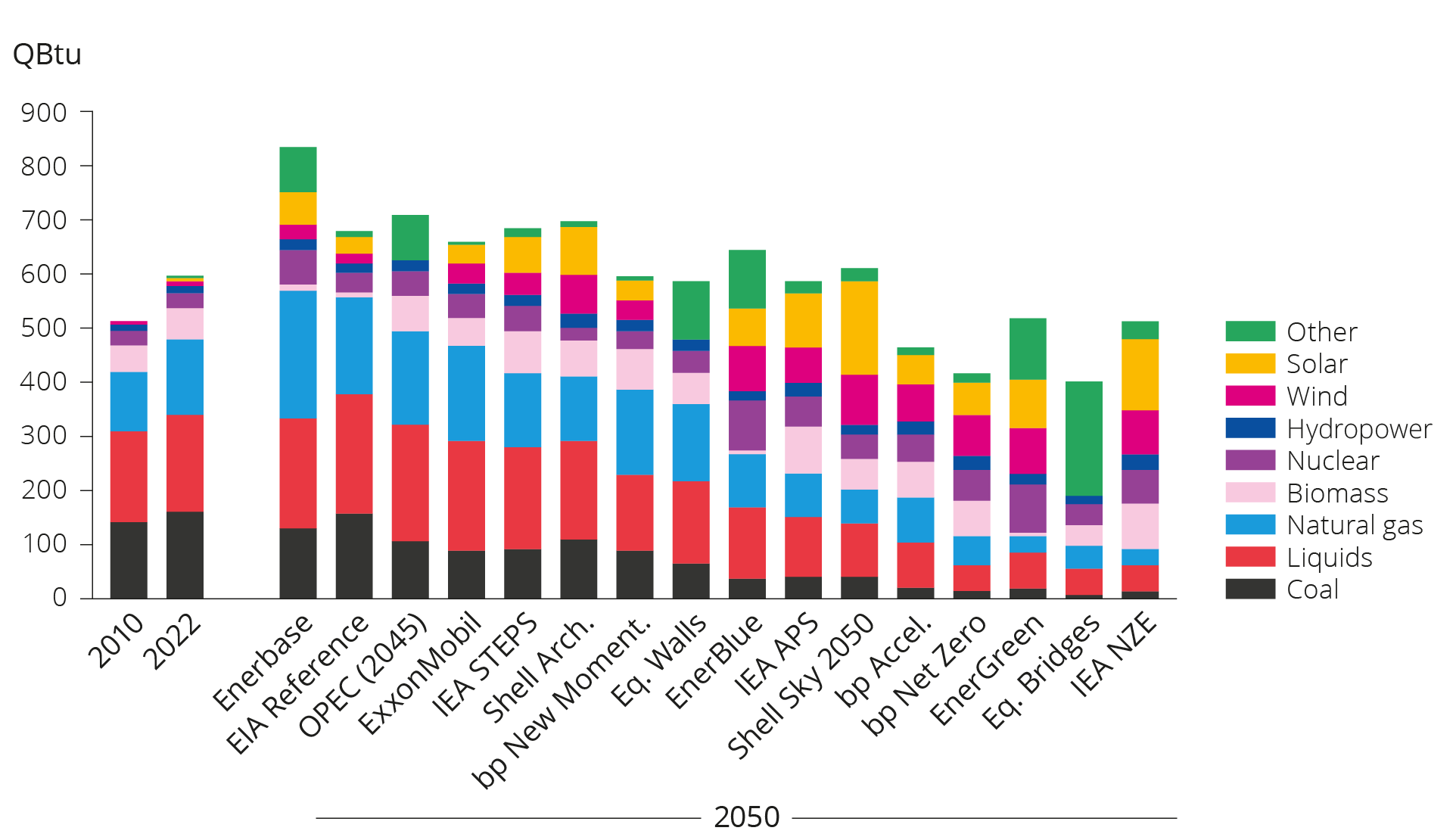

Oil and gas accounted for about 55 per cent of total global primary energy consumption in 2023(2). According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and other analyst communities, there will still be a need for oil and gas in 2050, see figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Global primary energy demand in 2050, different energy forecasts and scenarios. Source: Resources for the Future, 2024; British thermal units – Btu.

This figure was prepared by the US-based independent research foundation Resources for the Future (RFF)(3). Each year, RFF compares various selected long-term energy forecasts and scenarios in an effort to identify primary trends in global energy consumption and production. In most scenarios, global demand for primary energy will either grow modestly or decline toward 2050. This will be the case despite the substantial expected increase in global population. The main reason for this is a global economy that is becoming more energy efficient.

Six of the scenarios show increased demand for oil/liquids leading up to 2050, while demand for natural gas rises in eight, which is half of the scenarios. Consumption will remain high after 2050, despite a decline in demand for fossil energy. This will be the case even in normative scenarios where global warming is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

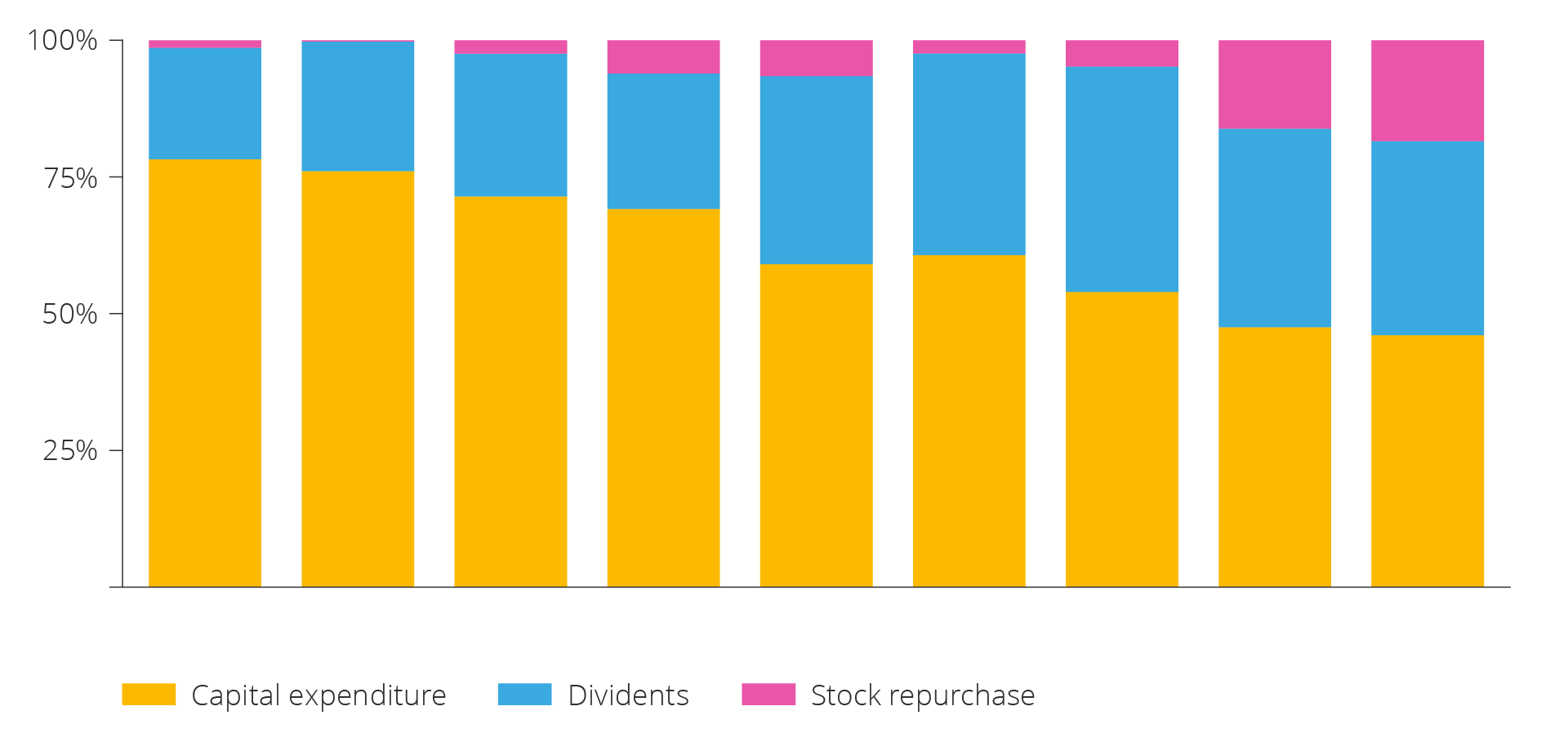

As production from current oil and gas fields is subject to natural decline, considerable investments in new capacity will be needed in order to meet future demand. In relative terms however, the industry(4) expends less capital on new investments than on dividend and share buybacks, see figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Expenditure on investments in exploration and recovery, dividend and share buybacks for the 30 largest oil and gas companies, 2015–2023 (Source: IEA 2024).

Companies will likely lean towards investing capital in oil and gas resources they find most profitable, which generally means oil and gas resources with low costs and low emissions per produced unit. These are often called 'advantaged' resources(5). The companies are therefore expected to seek out such advantaged resources, rather than investing in existing discoveries and fields challenged by high costs and emissions. Heavy oil and shale oil are examples of more challenged resources.

A study conducted by Wood Mackenzie(6) shows that there are few advantaged oil and gas resources available globally to meet future demand. Yet, these resources are plentiful on the NCS.

The Norwegian continental shelf is competitive

Nearly all oil and gas produced on the NCS is exported to Europe. This helps ensure a safe and stable energy supply for Europe.

The removal of Russian gas following the invasion of Ukraine laid bare the importance of stable gas deliveries from Norway to the rest of Europe. In 2022, Norway increased its gas exports by about 8 per cent or 9 billion scm (standard cubic metres). Deliveries from Norwegian fields have helped cover a higher share of Europe’s gas needs than before. The volume supplied by Norway now corresponds to about 30 per cent of the EU’s and UK's total gas consumption.

Without deliveries of these Norwegian resources, Europe would have a greater need to purchase LNG on the global market. This in return, would lead to a tighter global market, and would also have a greater impact on developing countries in Asia that need to import gas. Without deliveries from Norway, European gas and energy prices could be even higher.

Access to energy have increasingly become part of national security policies. Norwegian presence in the high north and Norway’s protection of critical societal functions such as gas infrastructure, will likely only become more important moving forward.

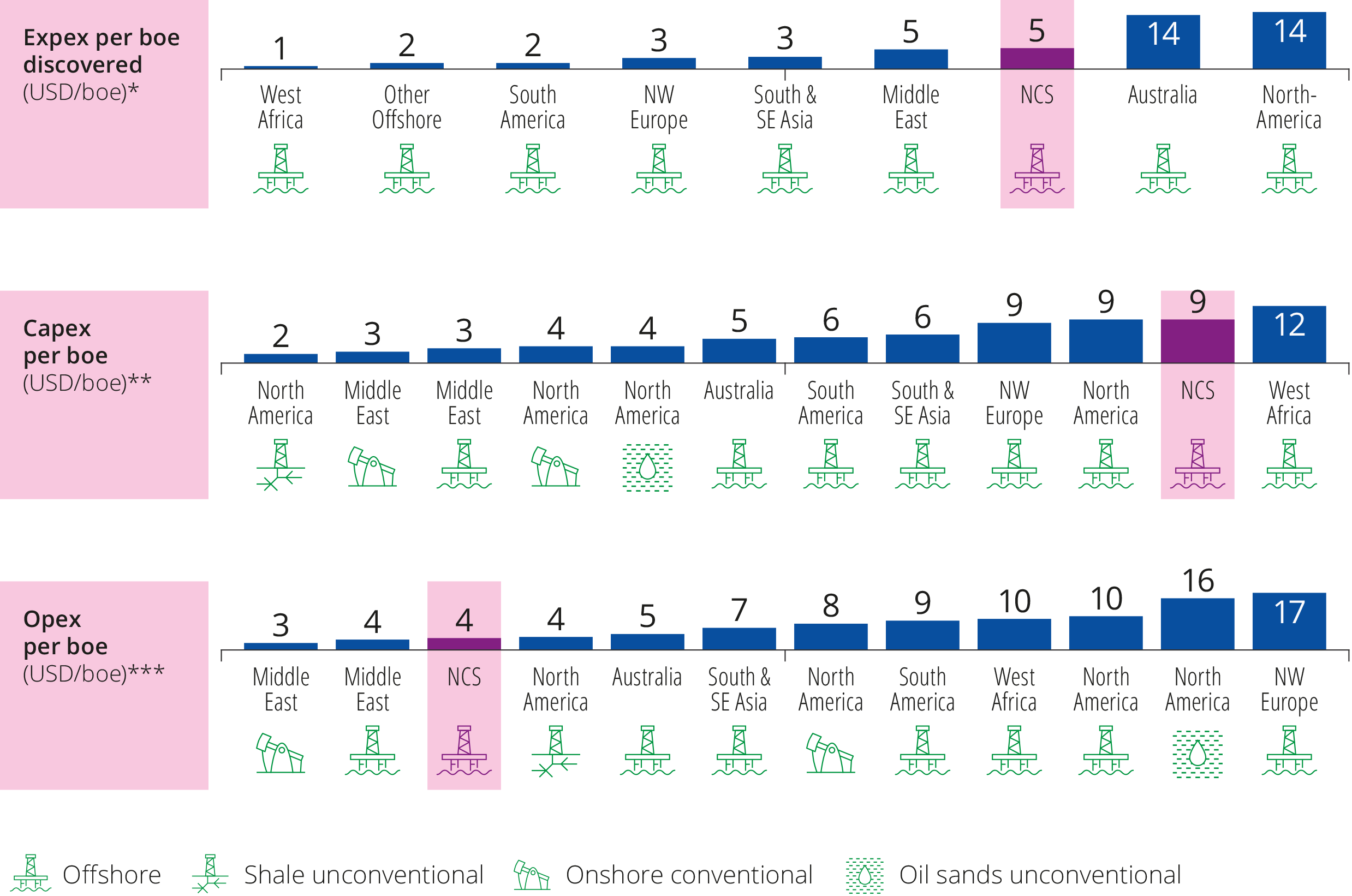

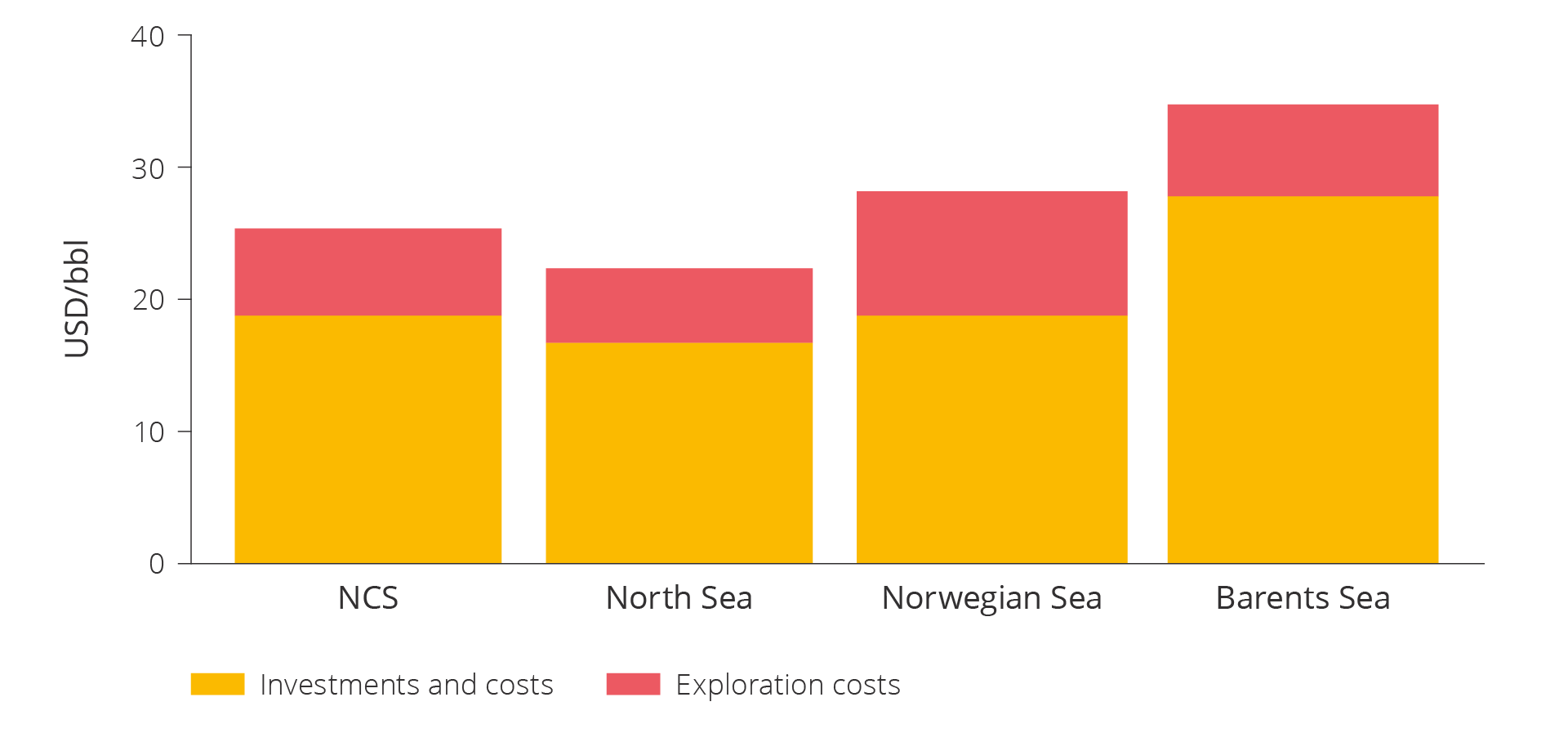

In spite of somewhat higher exploration and development costs compared with other petroleum provinces, the NCS is well-positioned to remain a competitive producer and exporter of oil and gas.

The relatively higher costs are caused in part by the fact that activities take place far out at sea and under challenging weather conditions. Substantial remaining resources, well-developed infrastructure, low operating expenses and stable framework conditions make the NCS an attractive investment opportunity, see figure 3.3(7).

Figure 3.3 Unit costs for exploration, development and operations on the Norwegian shelf compared with other petroleum provinces in 2021.

*Exploration expenses per barrel; offshore only. Only includes commercial discoveries where public information is available. Average of 2019 and 2020.

**Greenfield capital expenditures related to sanctioned oil and gas fields in current year. Volume-weighted average of 2019 and 2020.

***Operating expenses do not include transport costs and tax. Only includes opex associated with the production of hydrocarbons in addition to sales, general and administrative expenses (Source: OG21 2021).

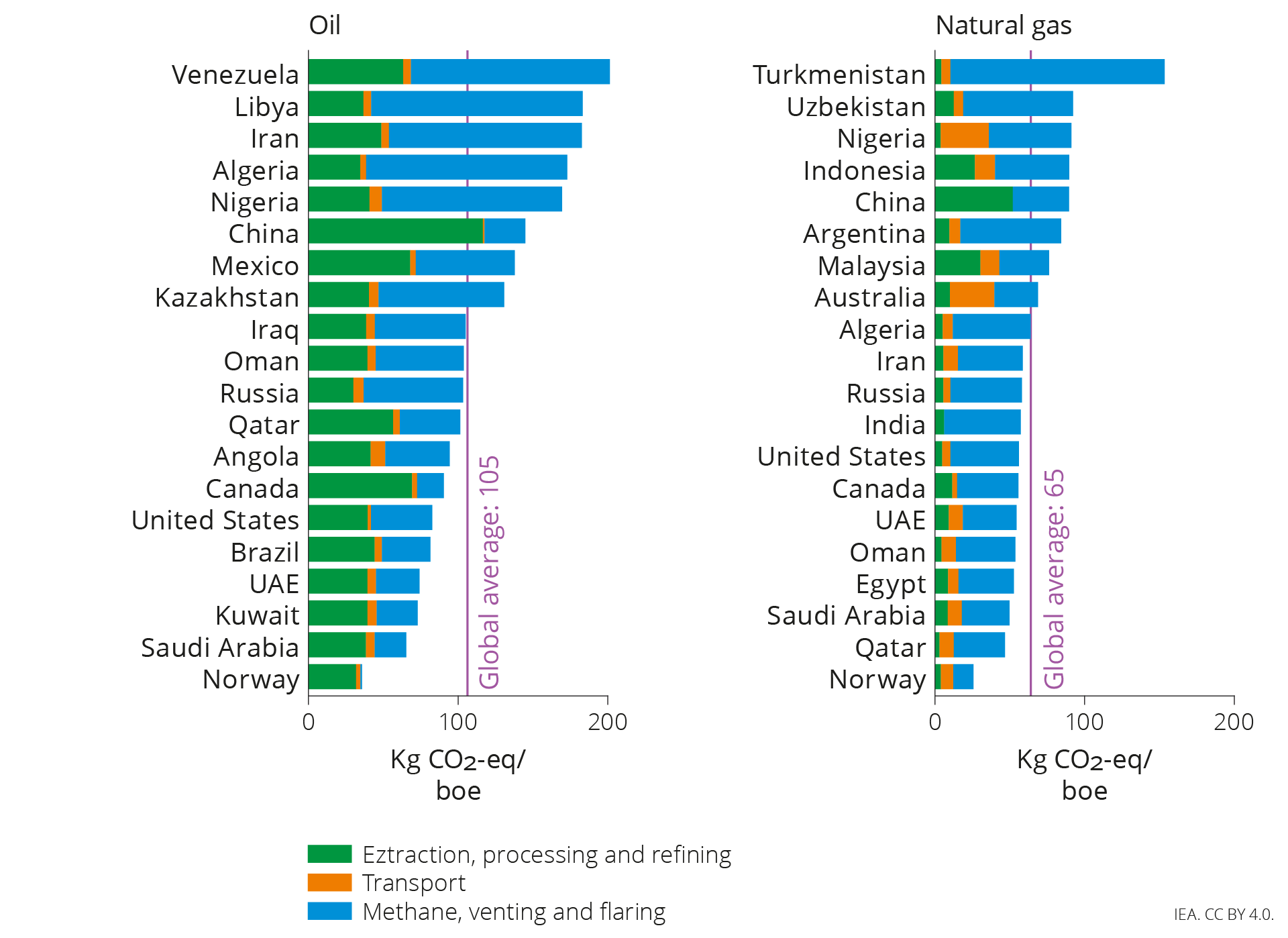

The NCS has very low greenhouse gas emissions per produced unit compared with other petroleum provinces, see figure 3.4(8).

Figure 3.4 Comparison of average emission intensity in kg CO2 equivalent/bbls of oil equivalent in 2022 for the largest oil and gas producers (Source: IEA 2023b).

Need for considerable investments moving forward

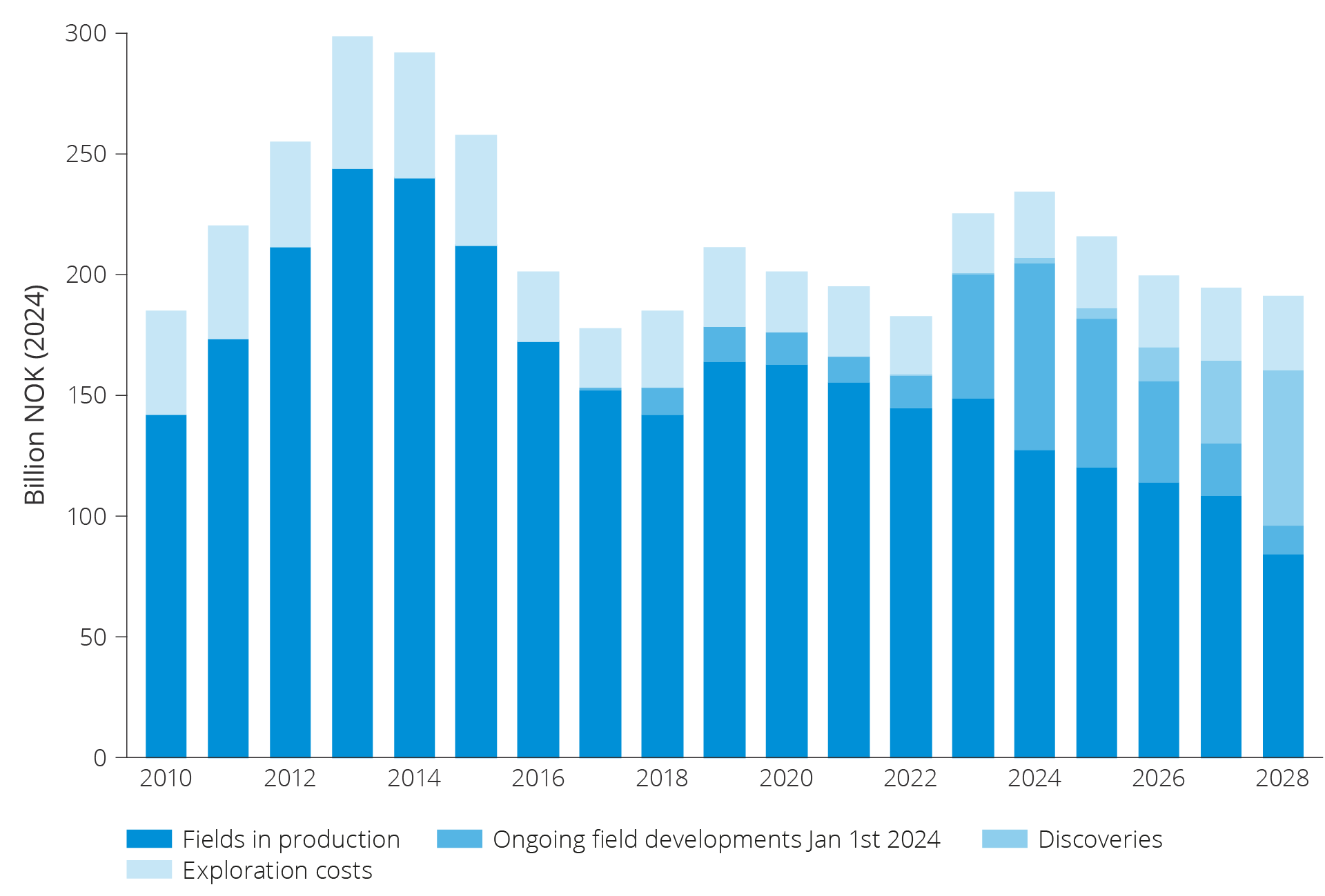

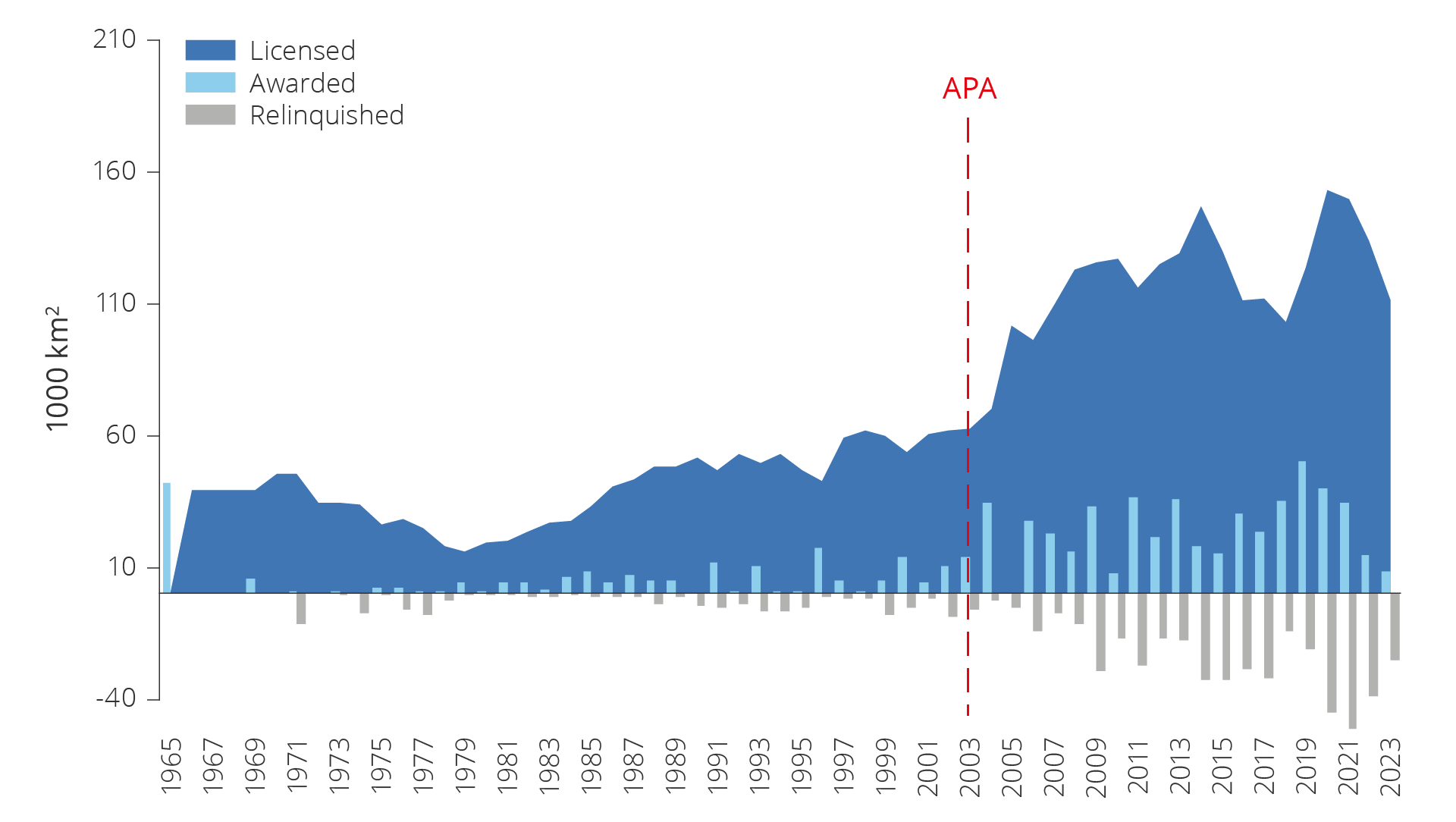

Petroleum investments increased sharply in 2023 after declining for three years straight, see figure 3.5. Investments in field developments were the main contributor to the increase, while the rise in exploration was more moderate.

The increase in 2023 must be viewed in context with high petroleum prices and the temporary changes in the petroleum tax rules that were implemented in connection with the oil price plunge in the spring of 2020. This ensured that plans for development and operation (PDOs) for as many as 13 new field developments were submitted in 2022. Several investment decisions were also made for further development of operating fields and improved recovery on existing fields.

The high number of field developments will contribute to stable activity levels moving forward. In a longer perspective, the decline in remaining resources is eventually expected to lead to lower investments in oil and gas production.

Figure 3.5 Historical petroleum investments and projections for future petroleum investments on the NCS.

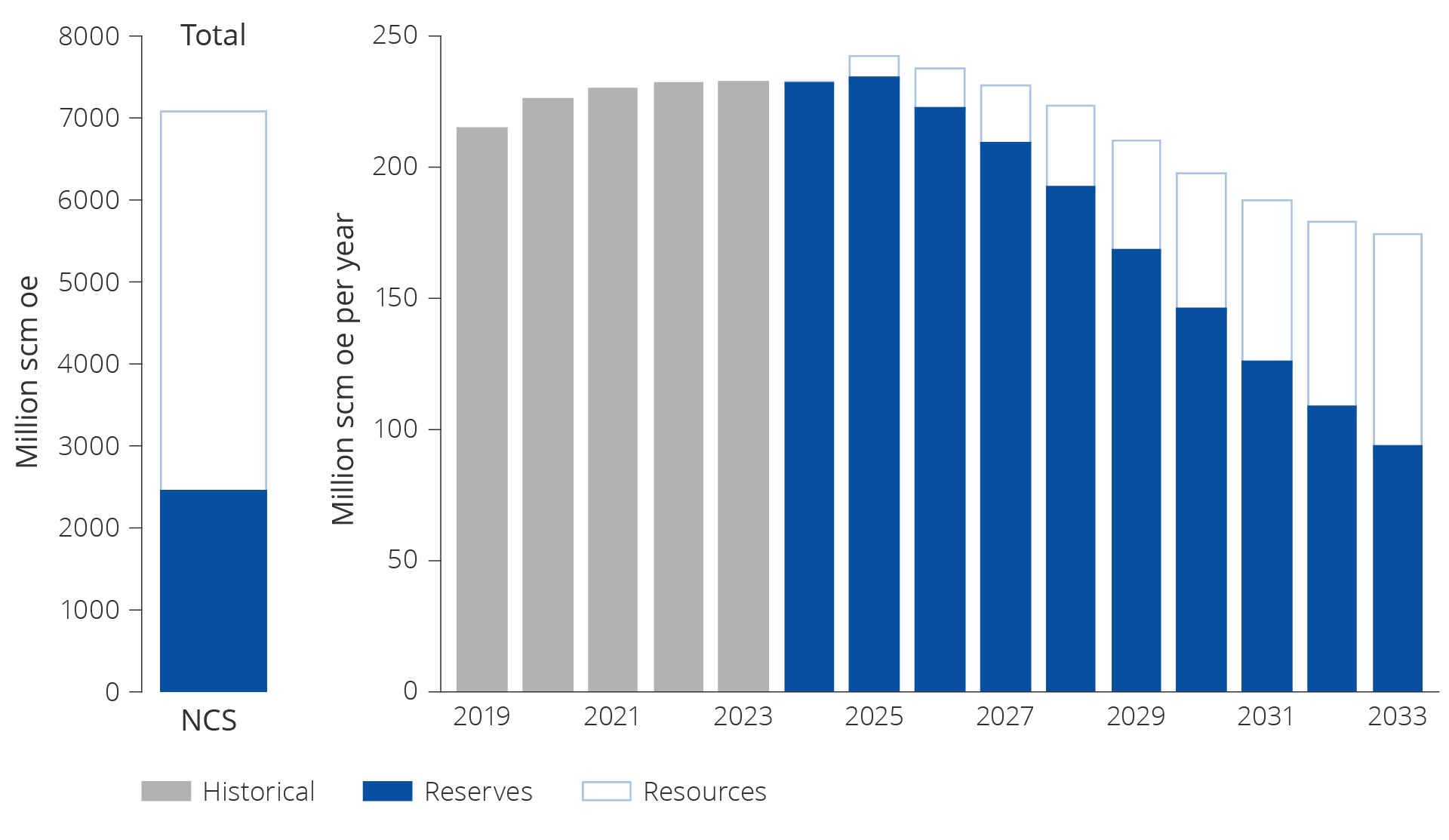

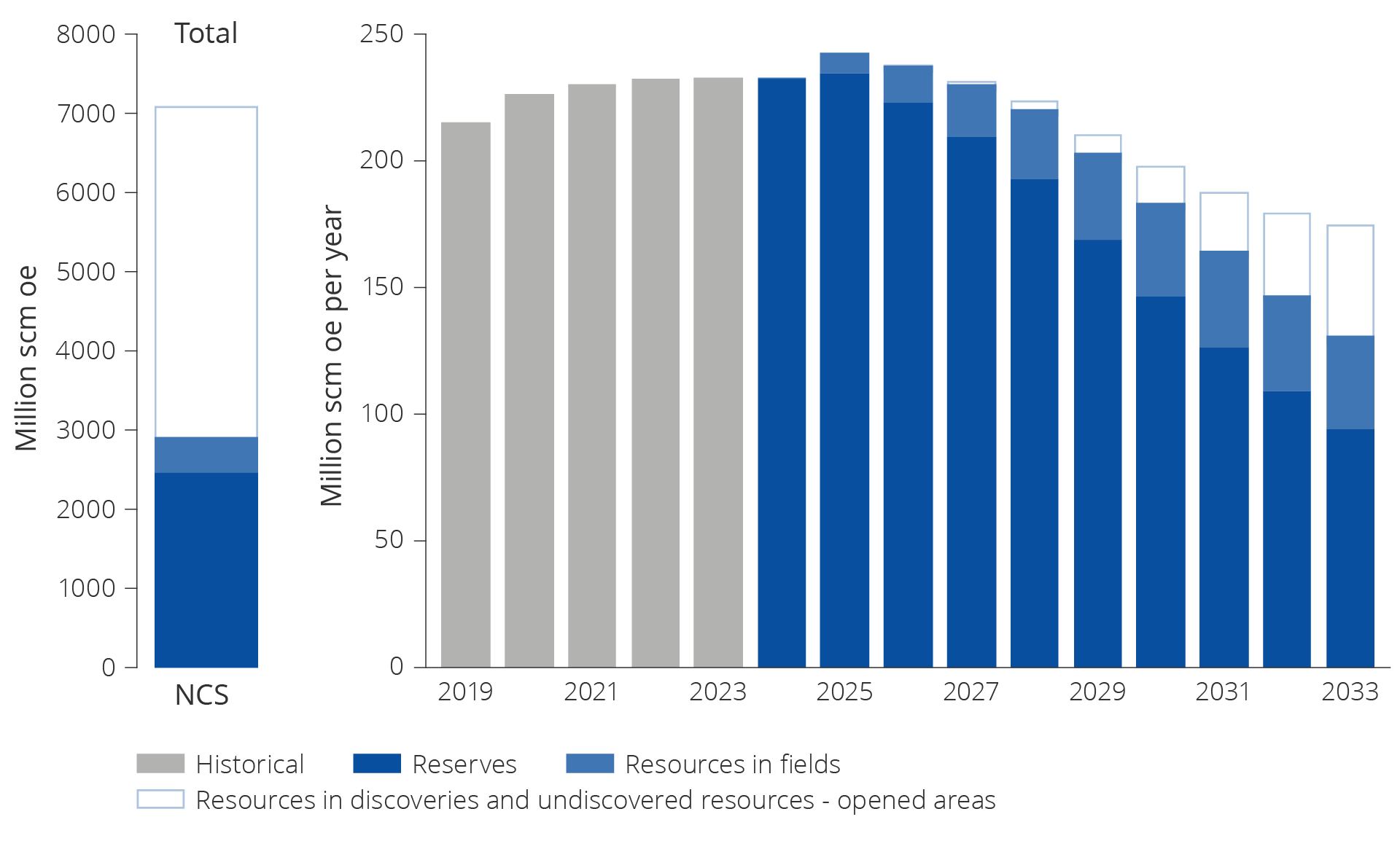

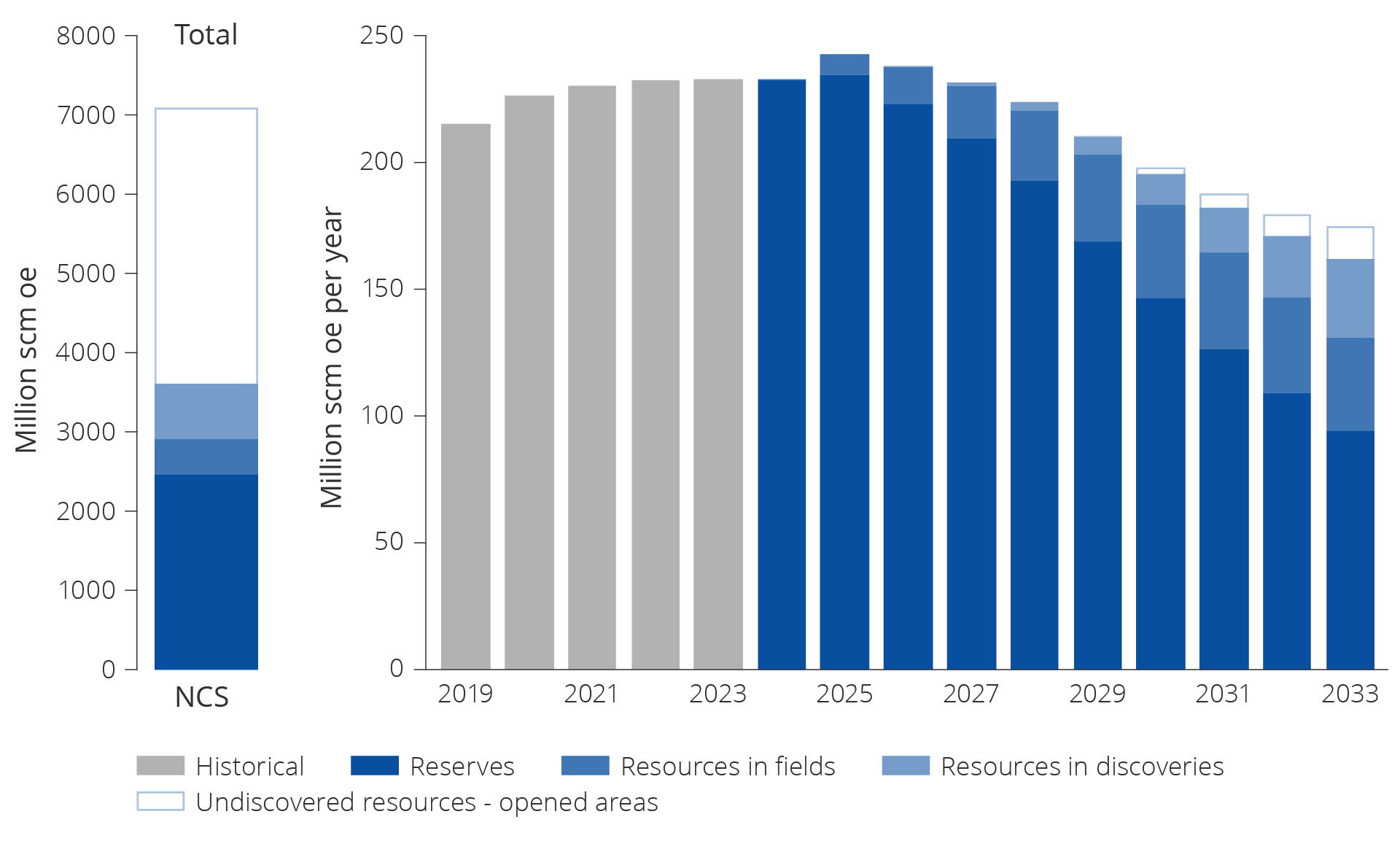

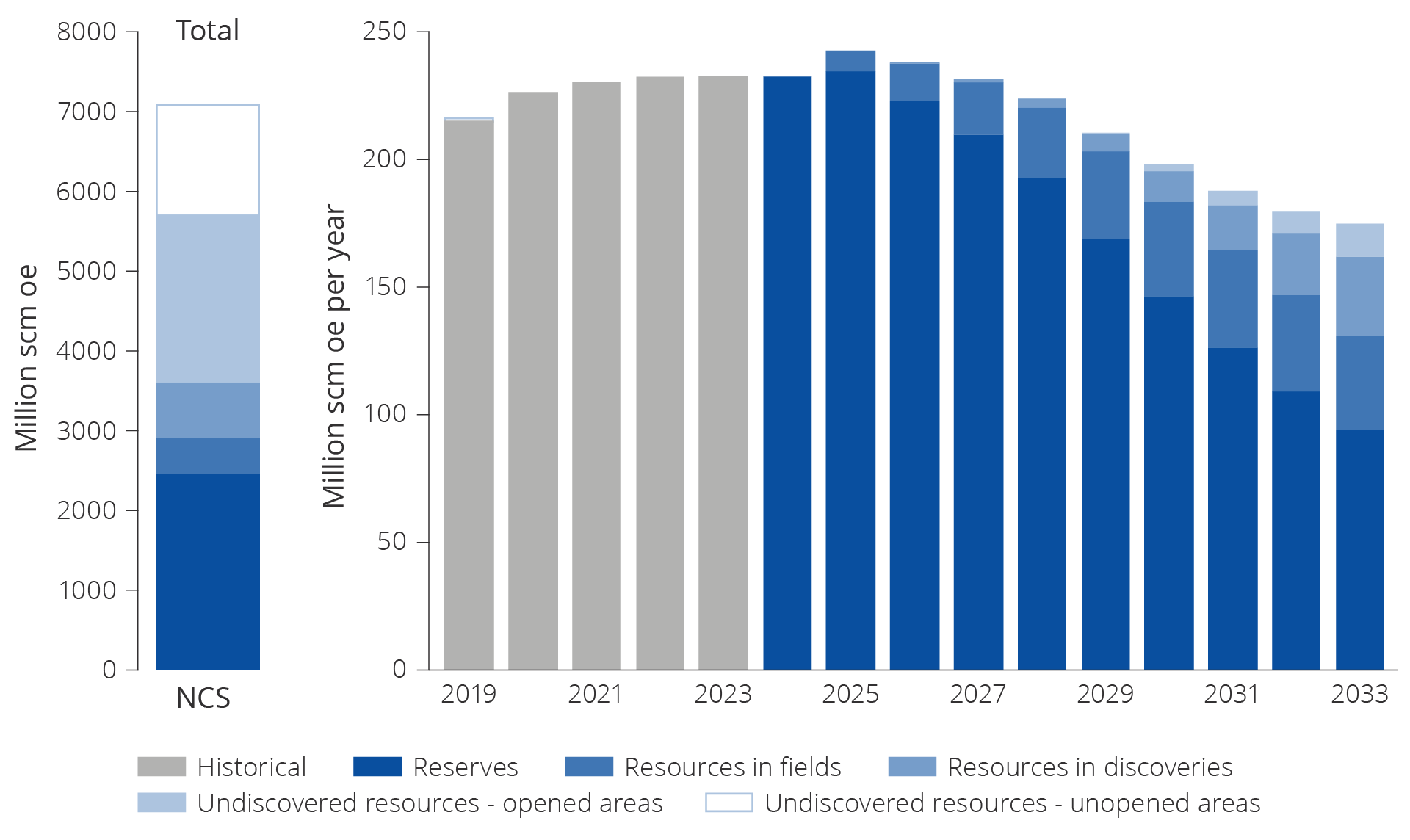

Petroleum production on the NCS increased slightly in 2023 in relation to 2022, but has been on plateau more or less since 2021. It is below its highest level in 2010. At the same time, gas production declined somewhat from record-high levels in 2022. The production of petroleum has increased each year starting in 2020 (Figure 3.6) and is expected to increase further in 2024 and 2025. The Norwegian Offshore Directorate projects that the level in 2025 will be the highest since 2006.

Production from existing fields will presumably decline after 2025, and production and exports from the NCS will gradually start to fall if no action is taken.

Figure 3.6 Production history and forecasts by resource class (Resource Accounts as of 31 December 2023(7) RNB 2024).

In order to slow the decline in production, the companies will need to make more and larger discoveries and complete additional projects for improved recovery. The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's assessments indicate that In 2033, about one-half of total production will be from projects that have not been approved as of June 2024 (see resource classification below).

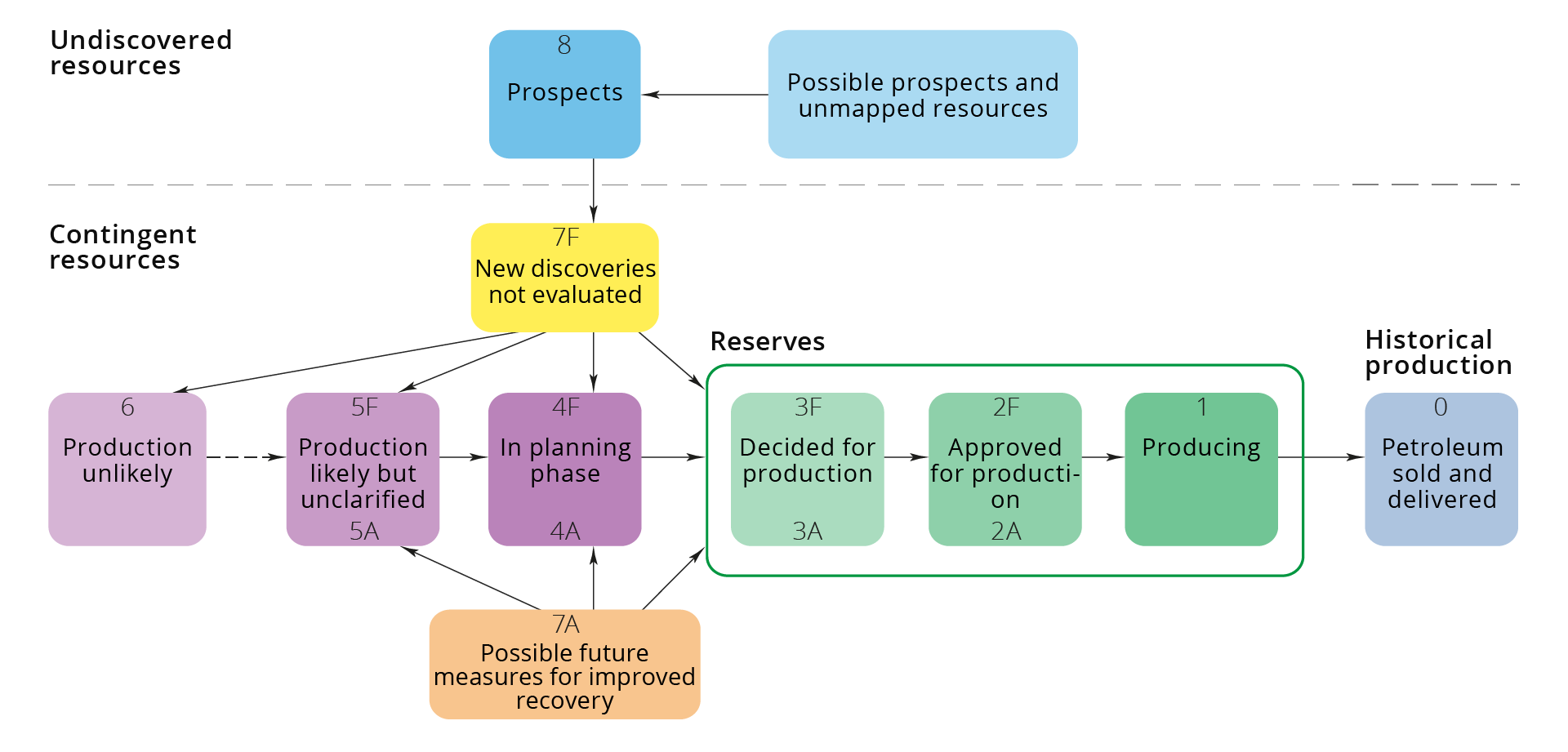

Resource classification

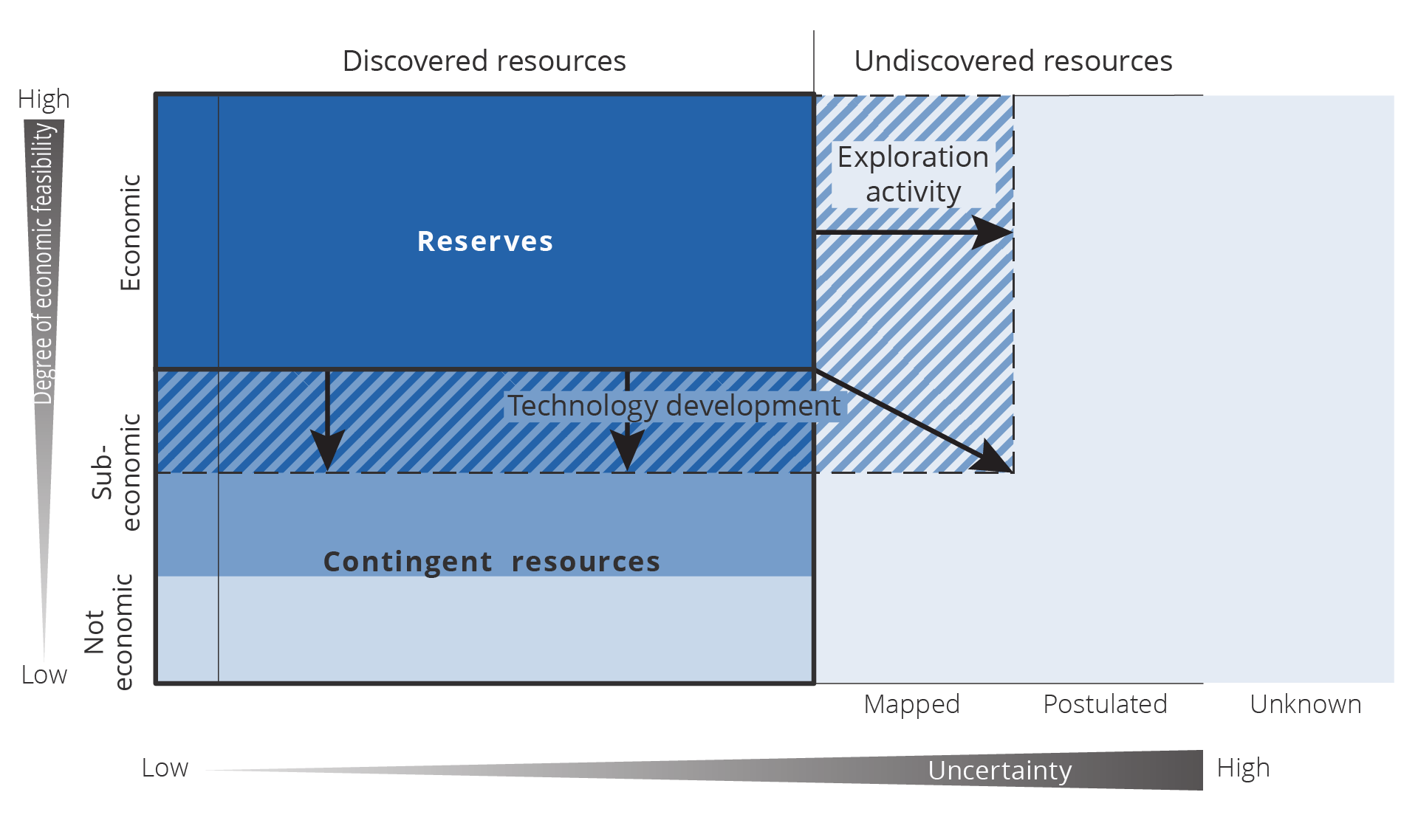

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource classification system is used for petroleum reserves and resources on the NCS (figure). This system is structured in such a way that the authorities receive the most uniform possible reporting from licensees as input to the Directorate's annual updating of the resource accounts.

"Resources" is a collective term for all oil and gas that can be recovered. They are classified in the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource classification system according to their level of maturity, with regard to how far they have come in the planning process from discovery to production.

Developed in 1996, the classification system was revised in 2001 and 2016. Changes in 2016 primarily involved language improvements, including new designations for certain resource classes. The classification relates to the total recoverable quantities of petroleum.

The system is divided into three classes: reserves, contingent resources and undiscovered resources. All recoverable petroleum quantities are called resources, and reserves are a special category of these. Reserves are the petroleum quantities covered by a production decision. Contingent resources cover both recoverable quantities which have been discovered but are not yet subject to a production decision, and projects to improve recovery from the fields.

The classification utilises the letters "F" (first) and "A" (additional) respectively to distinguish between the development of discoveries and deposits, and measures to improve recovery from a deposit. Undiscovered resources are petroleum quantities which could be proven through exploration and recovered. The quantities produced, sold and delivered form aggregate historical production(8).

Figure The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource classification system 2016.

New industries on the shelf

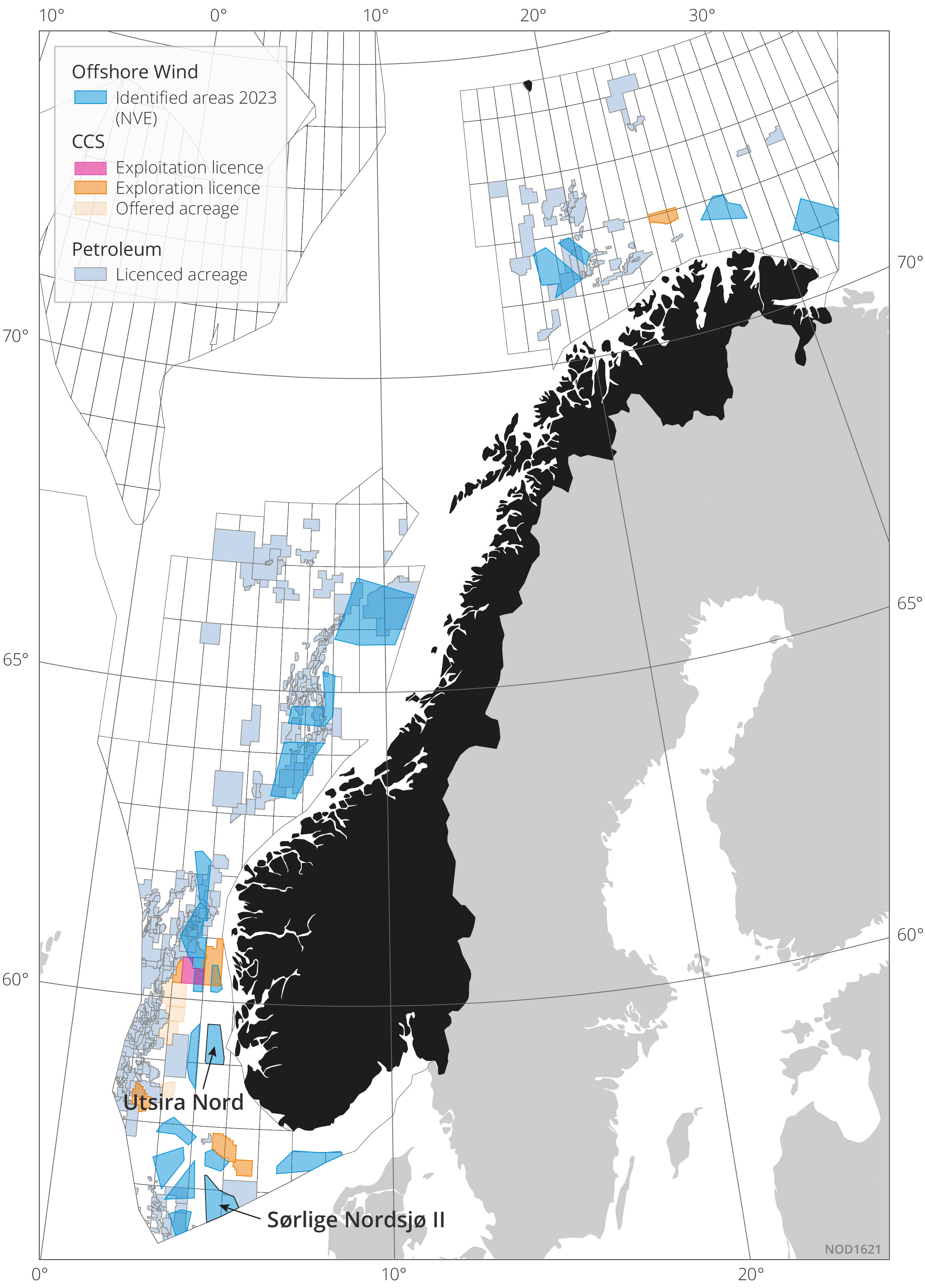

The need to reduce CO2 emissions means that multiple facilities will be needed to capture and store CO2 (CCS). CCS involves capturing CO2 from power generation and industry and transporting and storing it safely in geological formations deep underground. There are several suitable formations on the NCS.

The energy transition will also lead to an increased need for renewable energy, which is dependent on multiple minerals and metals. Some of which can be found on the NCS.

Seabed mineral extraction, CO2 storage and offshore wind may turn out to be profitable new industries on the NCS, presuming they are cost-effective and can compete with the alternatives. The costs can likely be reduced by leveraging synergies with the established value chains. At the same time, the established value chains can be strengthened through decarbonisation.

DownloadThree potential scenarios

In this chapter:

- The petroleum sector is very important for Norwegian value creation

- Remaining resources lay the groundwork for high value creation

- Exploration and technology development increase the reserve base

- Three scenarios leading up to 2050

- Base scenario

- Low scenario

- High scenario

- Consequences for future production and value creation

The petroleum sector is Norway’s largest industry measured by value creation, government revenues, investments and export value. It has vast ripple effects on the mainland. Overall, this means that the industry is very important for the Norwegian economy and has been since the adventure started more than 50 years ago.

The petroleum sector is very important for Norwegian value creation

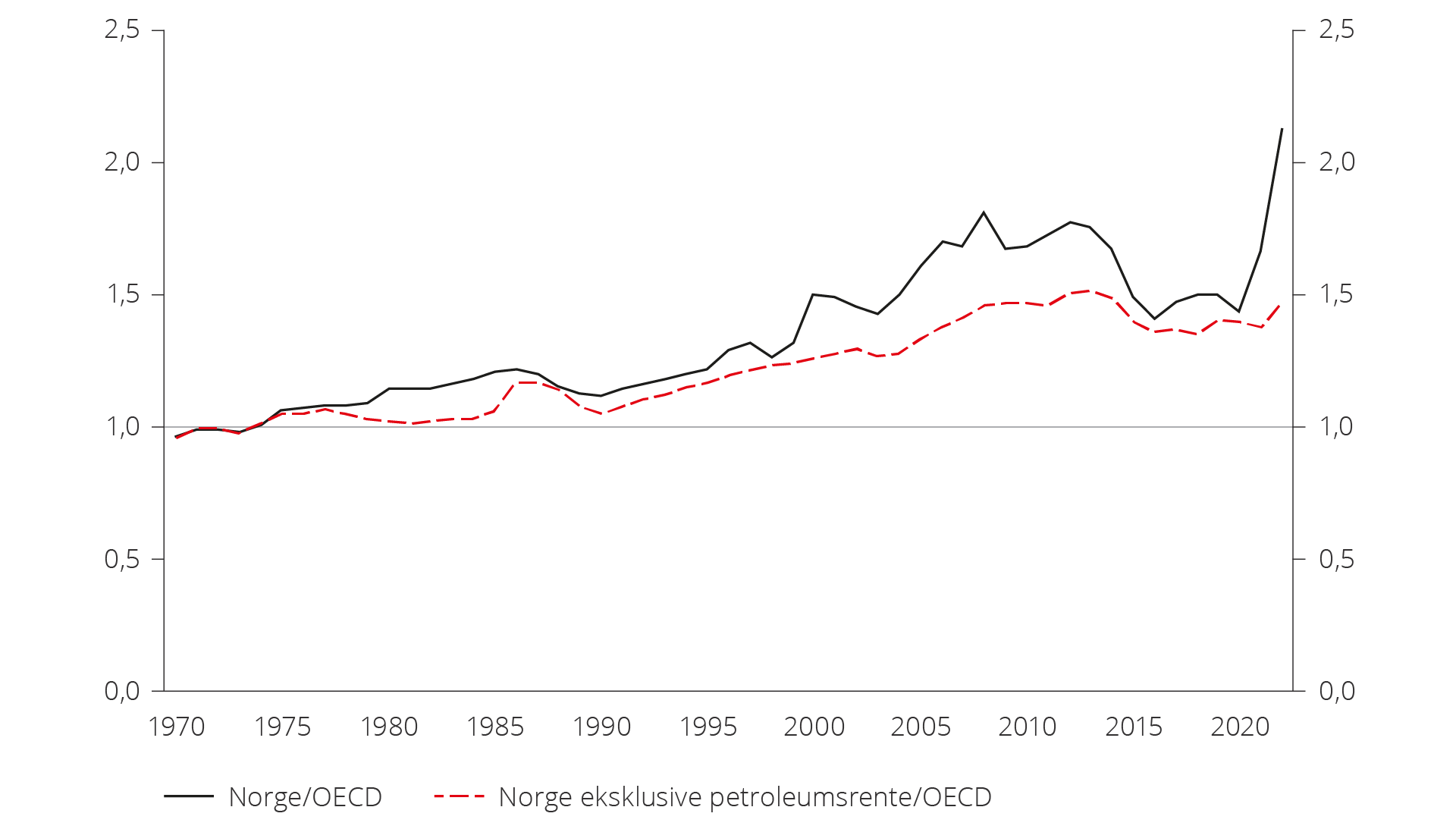

When Ekofisk was discovered in 1969, Norway’s GDP per capita (corrected for differences in price level and measured in shared currency) was just below the OECD average. Since then, value creation in the Norwegian economy has increased faster than in most other OECD countries, see figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 GDP per capita in Norway from 1970 to 2022 relative to the average of OECD countries during the same period (Source: NOU 2023:30).

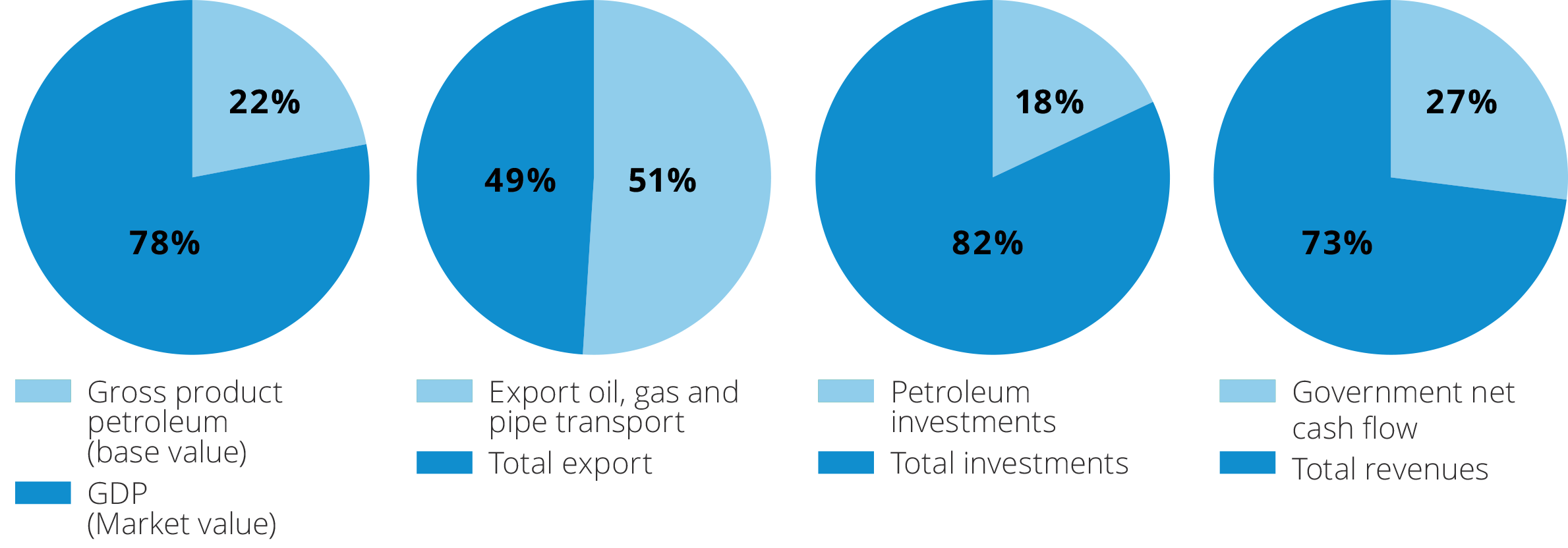

Over the last five years, production of crude oil and natural gas, including pipeline transport, accounts for 22 per cent of GDP, see figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 The petroleum sector's share of the Norwegian economy during the 2019–2023 period (Source: Statistics Norway and the Ministry of Finance).

During the same period, the value of exports of oil, gas and pipeline transport was 51 per cent of total exports. Furthermore, the petroleum activities account for 18 per cent of investments in capital stock and 27 per cent of government revenues.

Remaining resources are the foundation of high value creation

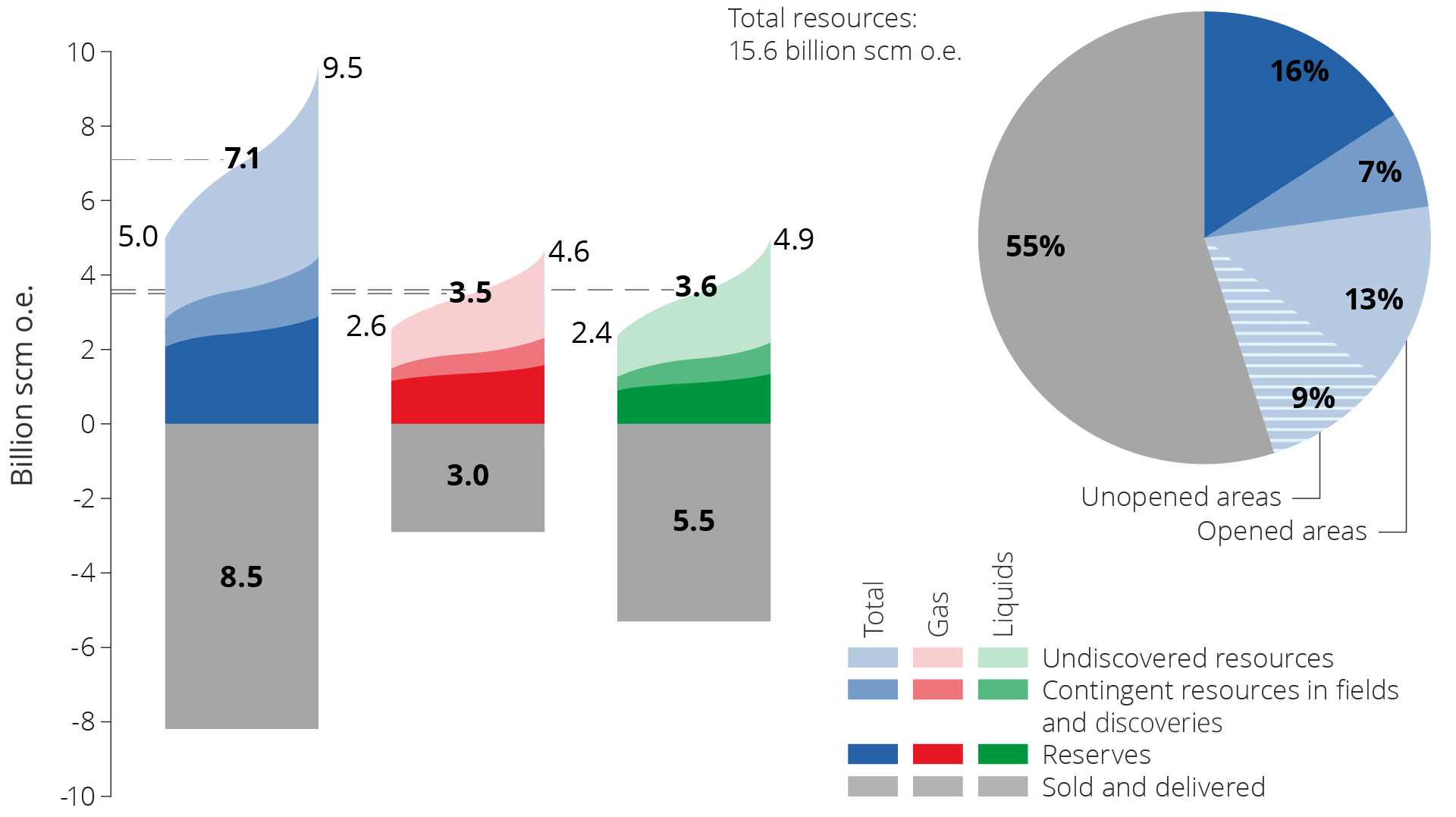

Remaining petroleum resources can be the foundation of significant production and value creation for several decades to come. The distribution of remaining resource volumes into resource classes along with the volume sold and delivered as per 31 December 2023 is shown in figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Petroleum resources and uncertainty in the estimates as per 31 December 2023.

The Resource accounts for 2023(11) estimate the overall expected resource volumes (including what has been sold and delivered) on the NCS at 15.6 billion standard cubic metres of oil equivalent (Sm3 of o.e.). The resources are distributed between 9.1 billion Sm3 of liquids (oil, condensate and NGL) and 6.5 billion Sm3 of gas.

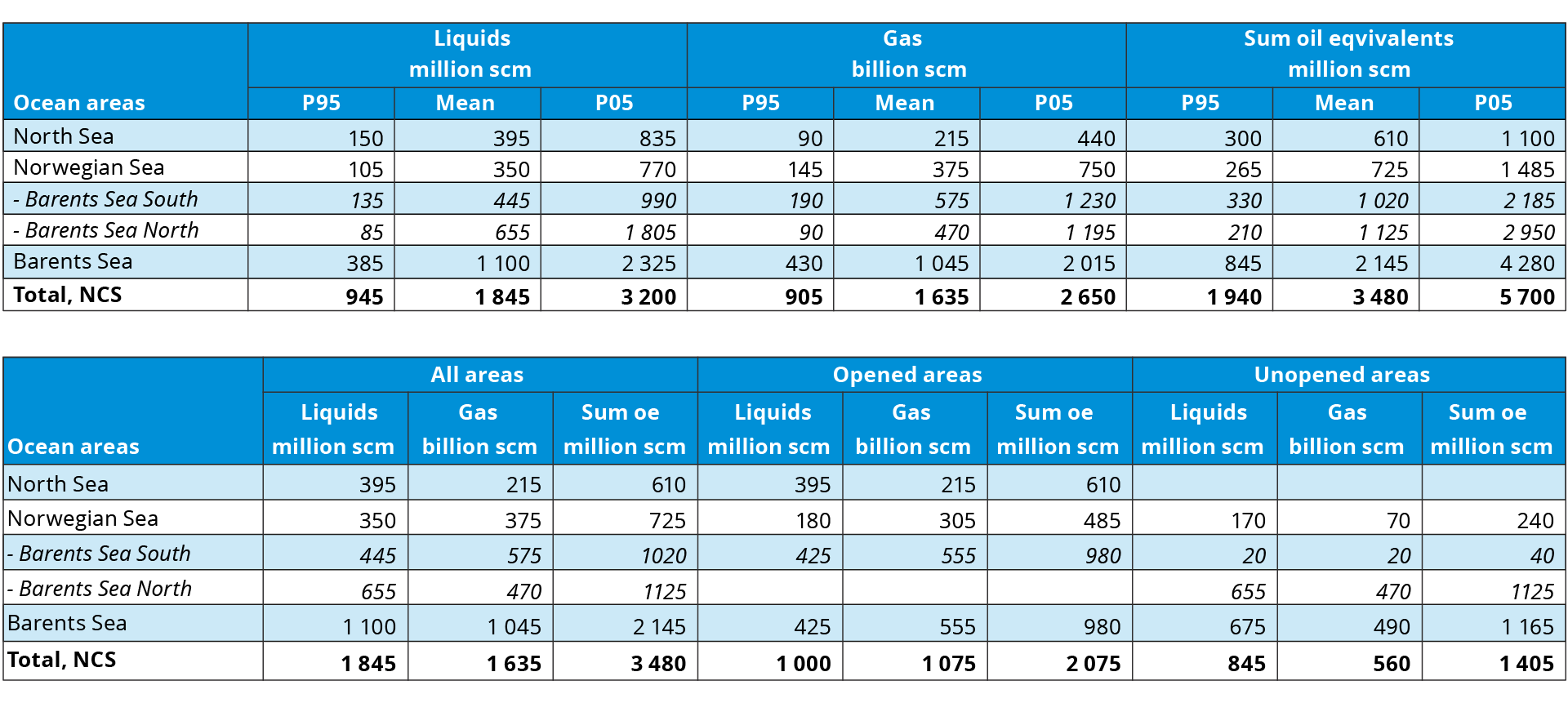

Uncertainty in the resource estimates is illustrated with a low and a high estimate in the figure. The distribution is shown for both liquids and gas. The uncertainty in the volume estimates is greatest for the undiscovered resources and declines with increasing access to geological information. As a result of this, the uncertainty is greatest in areas that have not been opened for petroleum activities, which this report refers to as "unopened areas".

Uncertainty in resource estimates

Uncertainty expresses the range of possible resource outcomes or results. It is most frequently described with the aid of low and high estimates.

For example, the Norwegian Offshore Directorate estimates the undiscovered resources on the NCS to be between 1.9 - 5.7 billion scm oe. This uncertainty is calculated using a statistical method known as Monte Carlo simulations. The high and low estimates are described utilising statistical concepts.

Where undiscovered resources are concerned, the Norwegian Offshore Directorate uses P95 for the low estimate. This means that, given the assumptions applied in the analysis, the probability of a result equal to or larger than the 95 value is 95 per cent. P05 is used for the high estimate, which means a five per cent probability that the result will be equal to or larger than the P05 value.

The expected value is the average value. This is generally defined as the arithmetic mean of all the outcomes in the statistical distribution. Widely used, it has the property that the expected value for various distributions can be summed to give a sum of distributions. The expected value is normally somewhat higher than the P50 value.

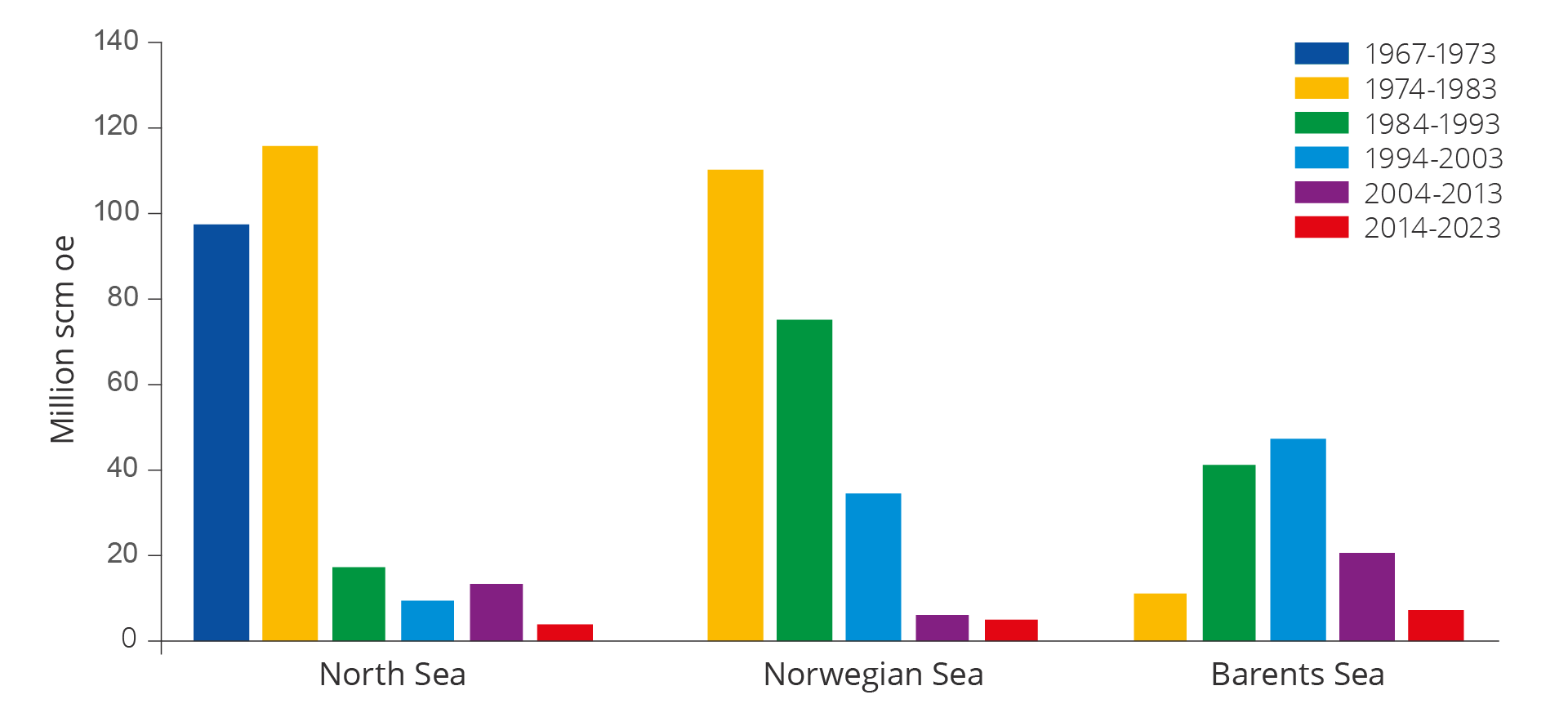

Exploration and technology development increase the reserve base

Developments in exploration activity, successful exploration and how quickly technology development and implementation take place in the sector are all crucial for production and value development on the shelf. High exploration activity and rapid technological innovation can yield an entirely different production development than low exploration activity and slower technology development.

These factors are driven by underlying global and regional issues. Geopolitical developments, climate policy and the development of renewable energy have consequences for the energy markets and future oil and gas prices. This affects profitability and activity on the NCS.

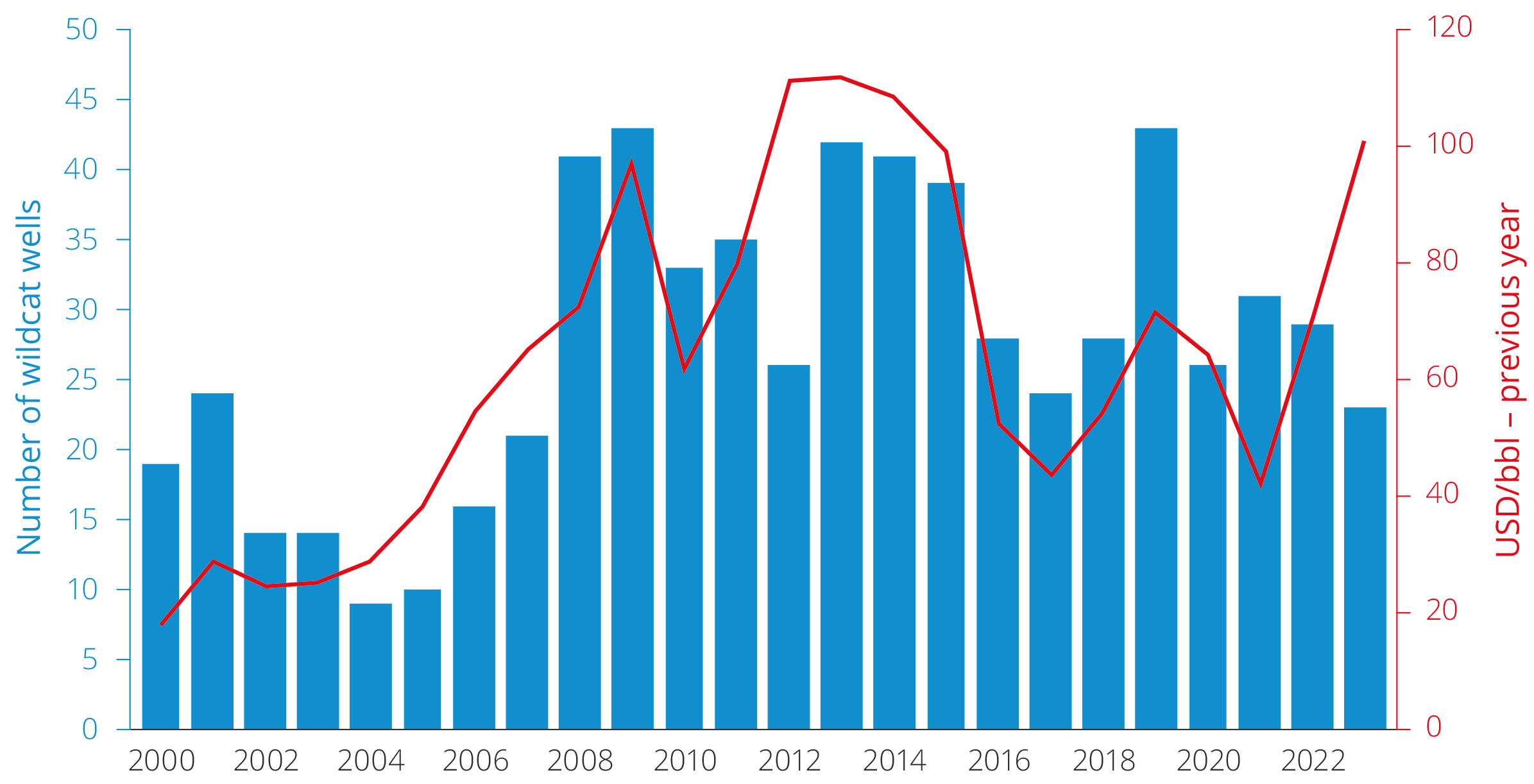

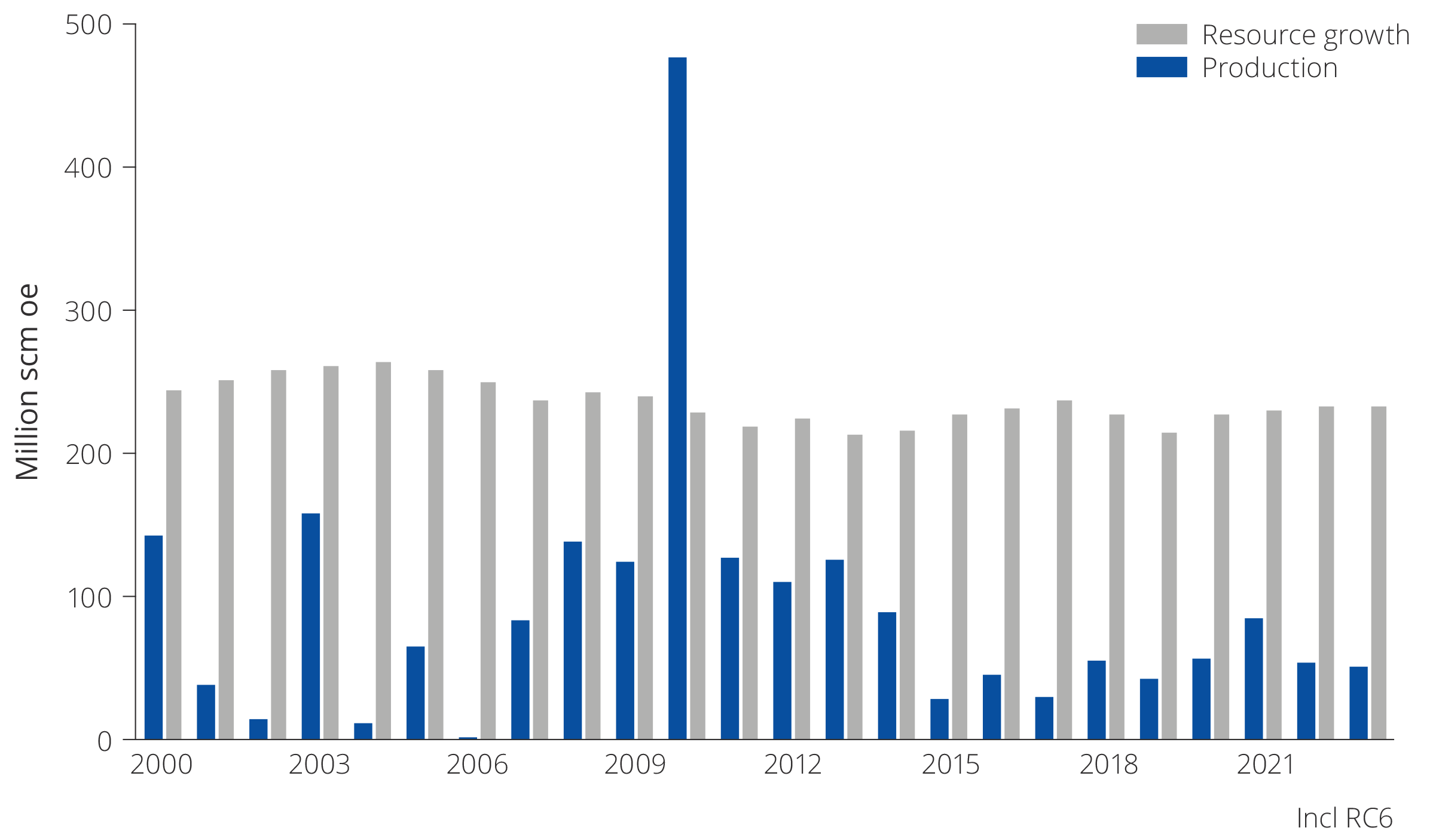

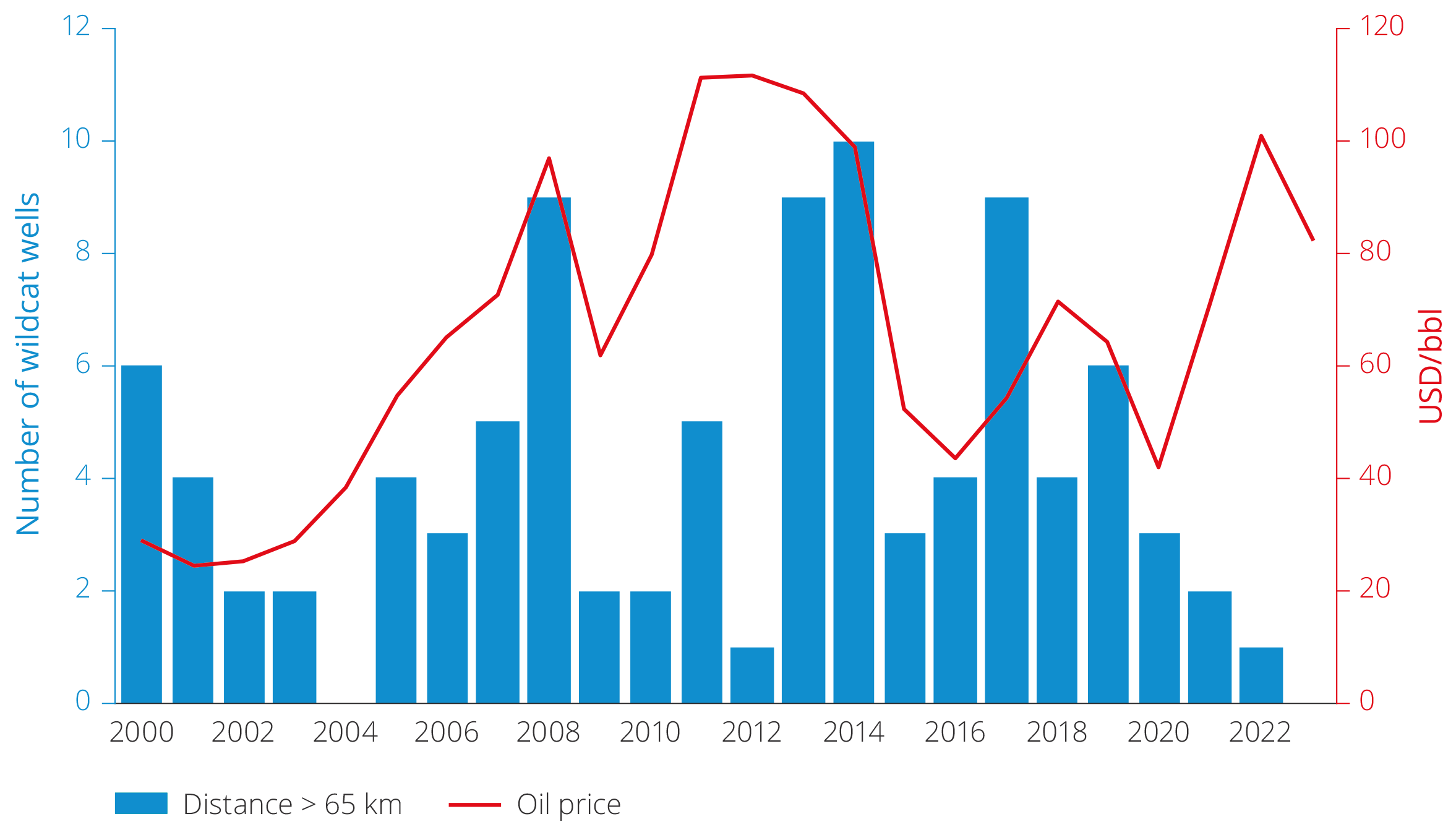

As in other petroleum provinces, the NCS has historically seen a positive connection between oil price developments and the number of wildcat wells the following year, see figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 Number of spudded wildcat wells and oil price the following year (2000–2023).

Higher oil prices increase the value of new oil projects and companies' income, which in turn affects the exploration budgets. During high-income periods, oil companies tend to focus on increasing oil and gas resources by exploring more and taking greater exploration risks. Periods with lower oil prices and income see cuts to exploration budgets. Only projects with the highest expected profitability and lowest risk are prioritised.

In addition to the number of wildcat wells, technology development also affects reserve growth from new discoveries. Improvements in technology for imaging the subsurface have been crucial for high levels of exploration success.

As the resources become increasingly hard to find, the development and implementation of new technology will become even more crucial for future exploration success. At the same time, it is necessary to continuously review the professional basis and knowledge about the resources on the NCS.

Improvements in field development technology and drilling help ensure that more of the smaller and marginal discoveries become profitable for development. Considerable additional volumes can also be recovered by implementing advanced recovery methods. One example is recovery from tight reservoirs (chapter 5 and chapter 6).

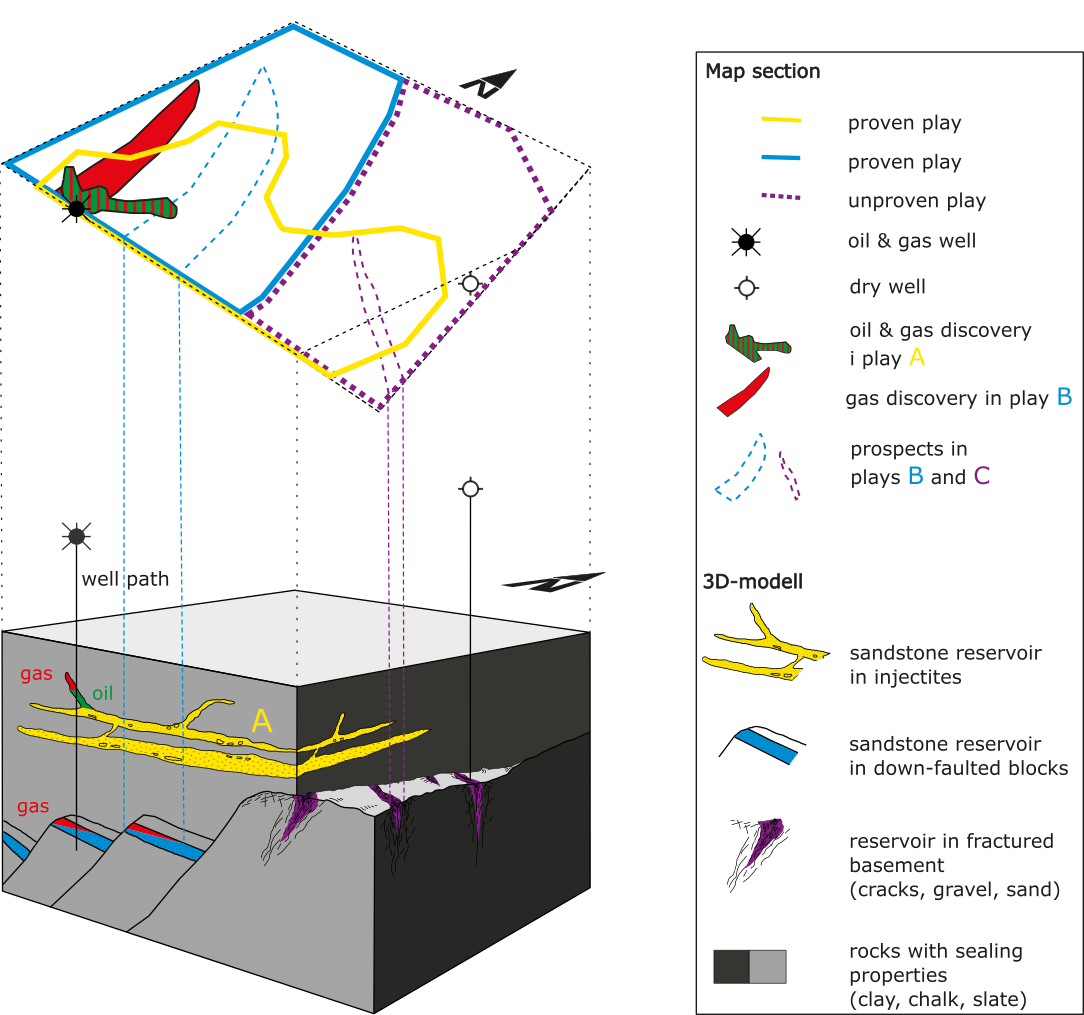

Figure 4.5 This figure is a modified version of the approach taken by American geologist Vincent McKelvey. The so-called McKelvey diagram(12) splits the oil in place into profitable and unprofitable resources and into discovered and undiscovered resources. When new technology and more information define new plays and discoveries are made, the reserve box expands toward the right. When technology development helps make marginal and unprofitable discoveries profitable to develop and recover, the reserve box expands downward. In an effort to reflect the possibility that unforeseen discoveries can still be made on the NCS, we have also added a category for unforeseen undiscovered resources(13).

Figure 4.5 illustrates how new technology and knowledge, as well as the ability to rapidly utilise new technology, can contribute to increase profitability for exploration, developing new discoveries and improved recovery on fields. The figure represents this as an increase in the reserve base; see resource classification, chapter 3.

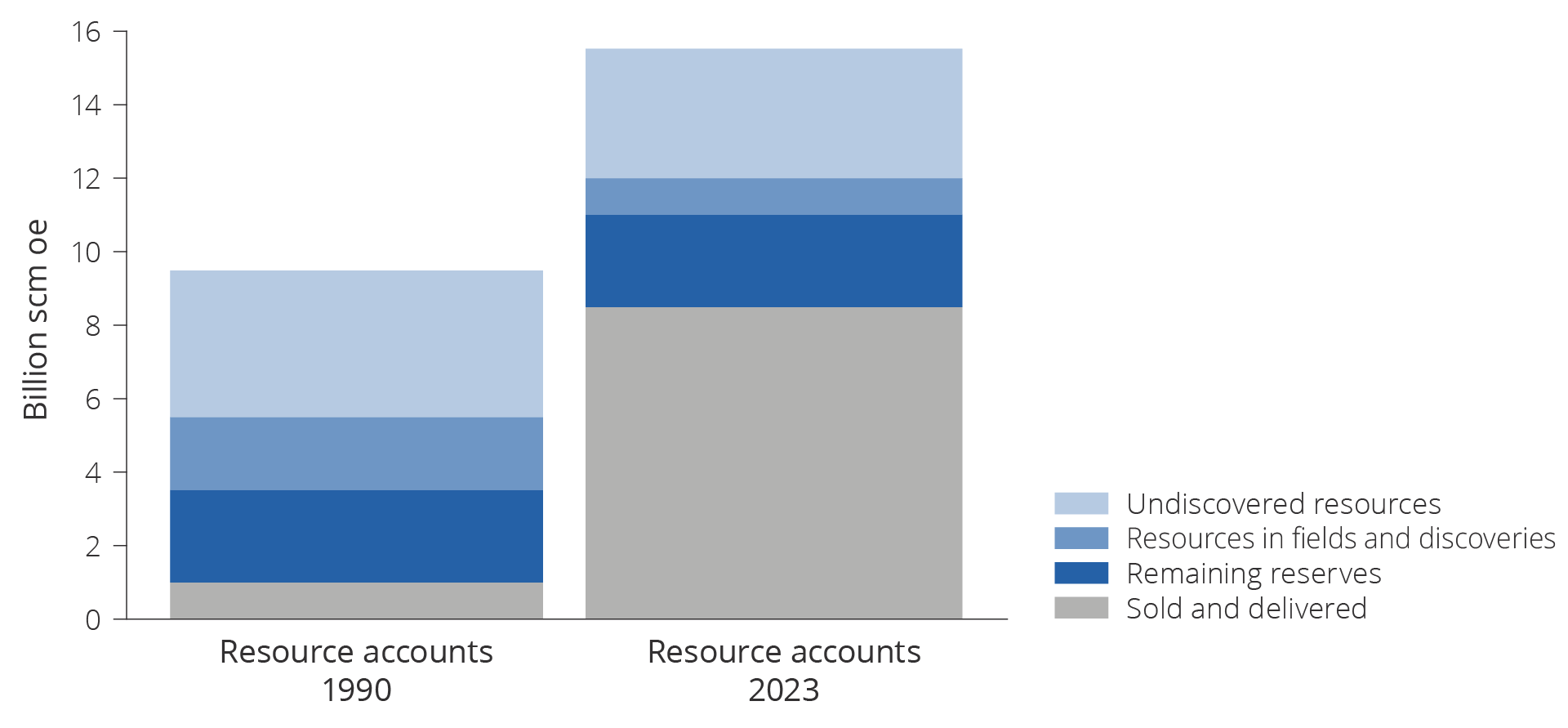

Historically, there has been a tendency to underestimate how technology development and increased knowledge about the subsurface have contributed to increased resource growth and higher production. Figure 4.6 shows the development in the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's assessment of overall resources in 1990 and 2023. The Directorate's resource estimate has increased by about 60 per cent during this period.

Figure 4.6. Growth in the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource estimate from 1990 to 2023.

Three scenarios leading up to 2050

The considerable uncertainty in the resource base, exploration activity and technology development make it difficult to create an unbiased forecast of future oil and gas production.

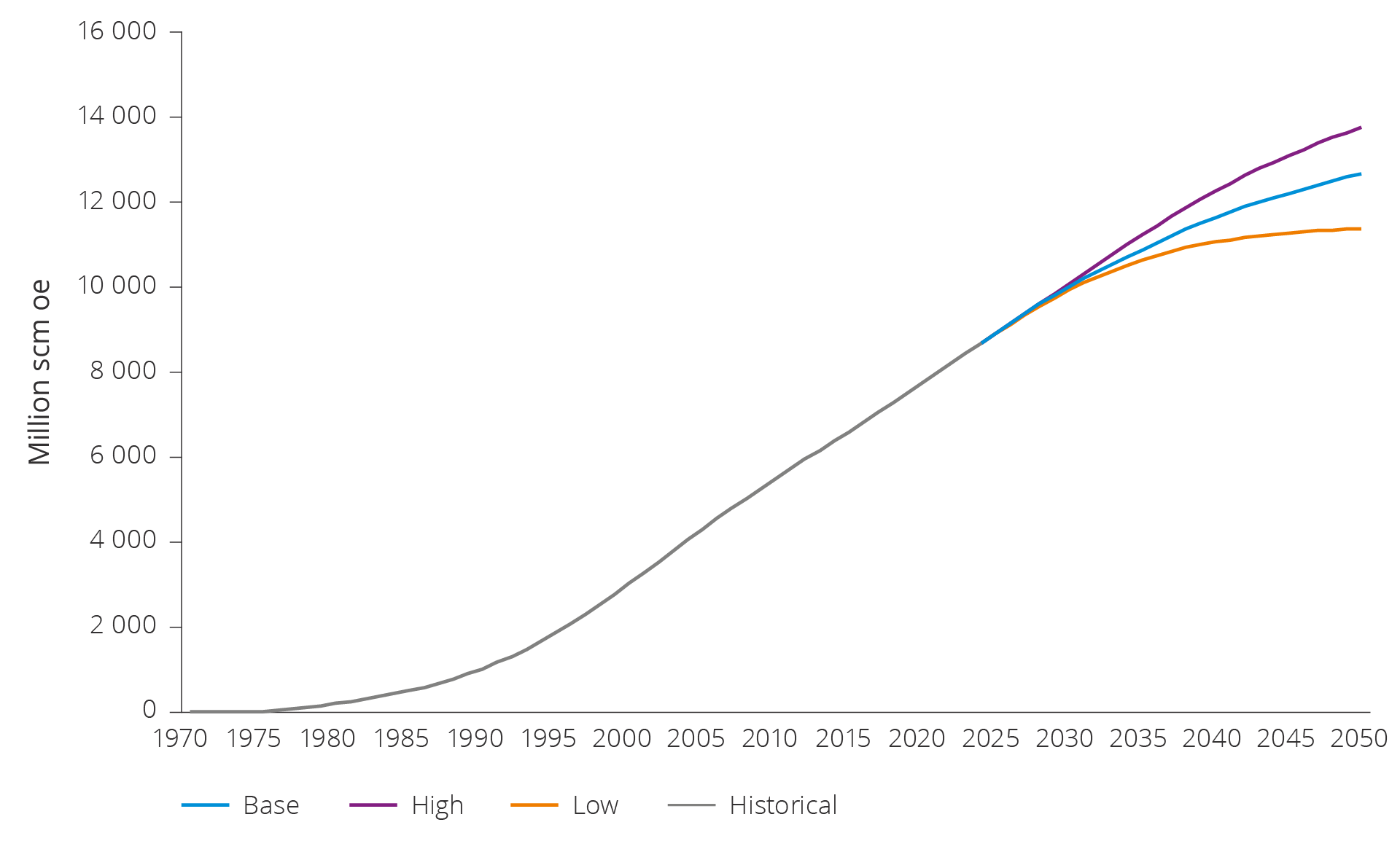

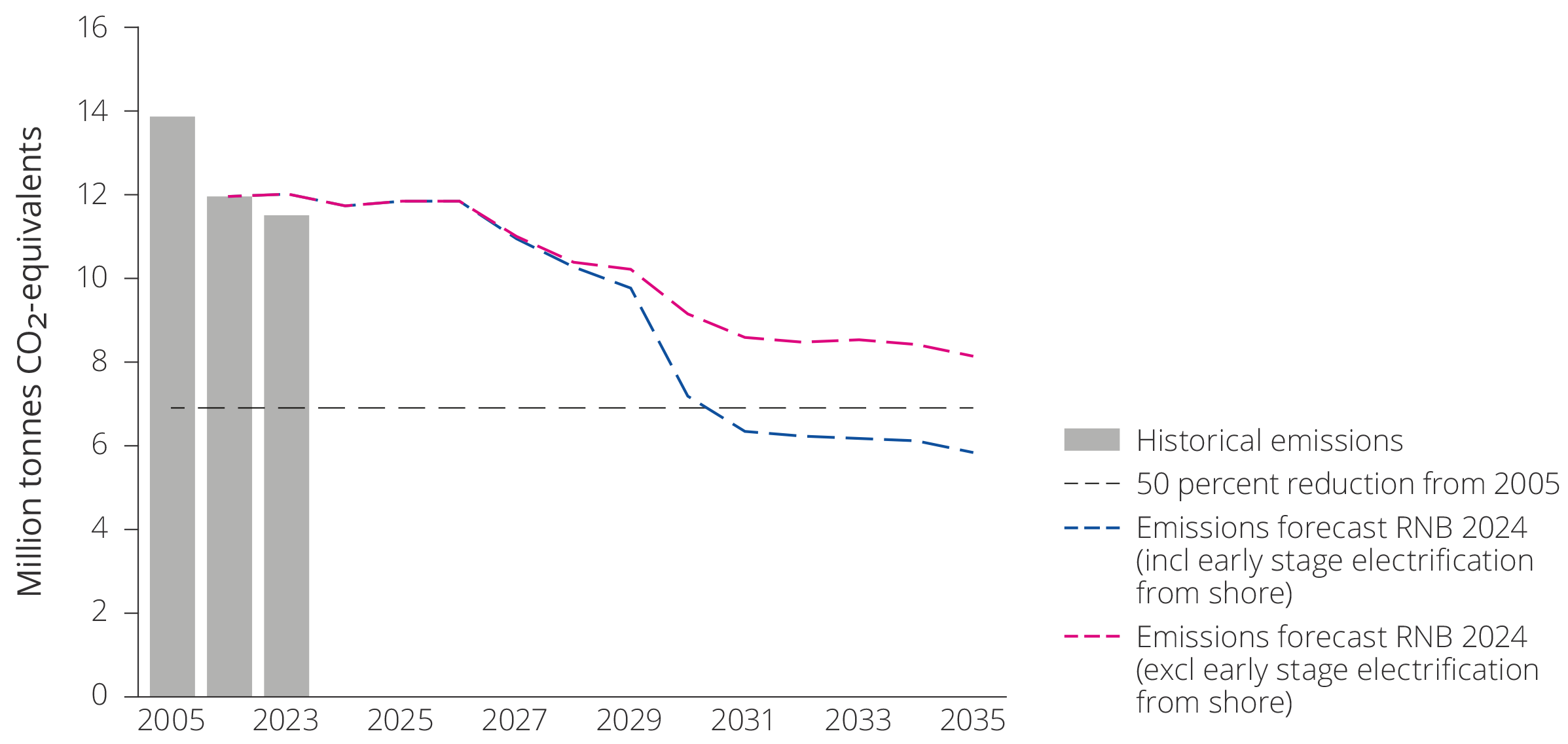

This is why the Norwegian Offshore Directorate has developed three scenarios for total petroleum production on the NCS leading up to 2050, which are better suited than a forecast to expand on the range of possible outcomes or opportunities for future production. The three scenarios were first published in the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate's resource report for 2022(14). They have now been updated with new data from the oil companies in connection with reporting for the 2024 revised national budget, see figure 4.7.

All scenarios show a decline in production, but the pace of this decline varies depending on exploration activity and technology development. The range of possible outcomes shows a significant spread in production in 2050.

The decline in production on the NCS in the three scenarios is within the interval for the global decline in oil and gas production the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and IEA have estimated is in line with successfully following up the Paris Agreement(14).

Figure 4.7 Three potential scenarios for production developments for total production on the NCS 2025–2050.

Method for developing potential scenariosMethod for developing potential scenarios

Production trajectories are established for fields, discoveries and improved recovery in each scenario by starting with data reported by the companies (reporting for the revised national budget (RNB)).

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's estimate for undiscovered resources in opened areas forms the basis for production from new discoveries. The production profile for new discoveries is derived from the scenarios' assumptions about exploration activity, discovery rate and lead times. Development solutions and associated cost and production profiles are developed for each discovery.

The model calculations for new discoveries are based on assumptions about typical development solutions (independent or satellite developments), main phase (oil or gas), resources, reservoir depth and distance to nearest infrastructure (both fields and pipelines). The cost level for exploration, development and production is based on historical costs on the NCS and expectations as regards future cost level and technology developments.

As production on the NCS is expected to gradually decline toward 2050, the infrastructure will need to be consolidated in order to keep unit costs down. This is reflected in the costs used as a basis.

The same market development is used as a basis for all scenarios. For computational purposes, the oil and gas price development from the 2024 revised national budget has been used as a basis. The Ministry of Finance's carbon price trajectories for use in socio-economic analyses are used for developments in the CO2 tax and emission credit price(16).

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate has calculated the profitability (net present value (7 per cent before tax)) for discoveries, fields and improved recovery. Only projects with positive net present value are included in the production profile. This yields a production cycle leading up to 2050 for each scenario. The scenarios vary as regards exploration activity and resource growth, capacity restrictions in infrastructure and industries, lead times and technology development.

Base scenario

In this scenario, liquids and gas production increases leading up to 2025, before it gradually declines in line with depletion of the resources. The gas share of total production increases over time.

Production development

Production reduces gradually from 243 million scm oe in 2025 to about 83 million scm oe in 2050 in line with a gradual production decline on the larger fields (base, figure 4.7). This is a reduction of about two-thirds from 2025 to 2050. This constitutes a significant dismantling of petroleum activities leading up to 2050.

Exploration activity and resource growth

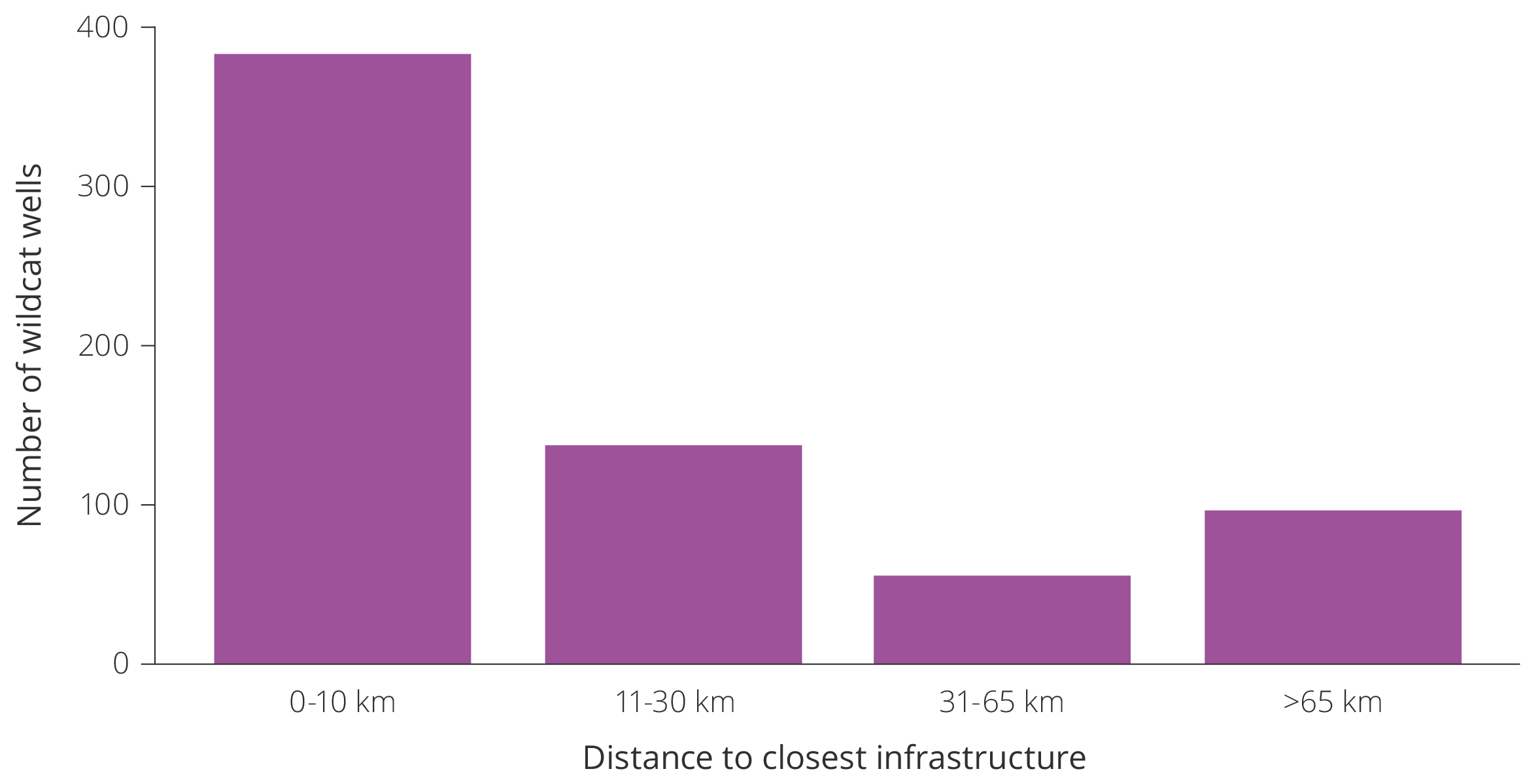

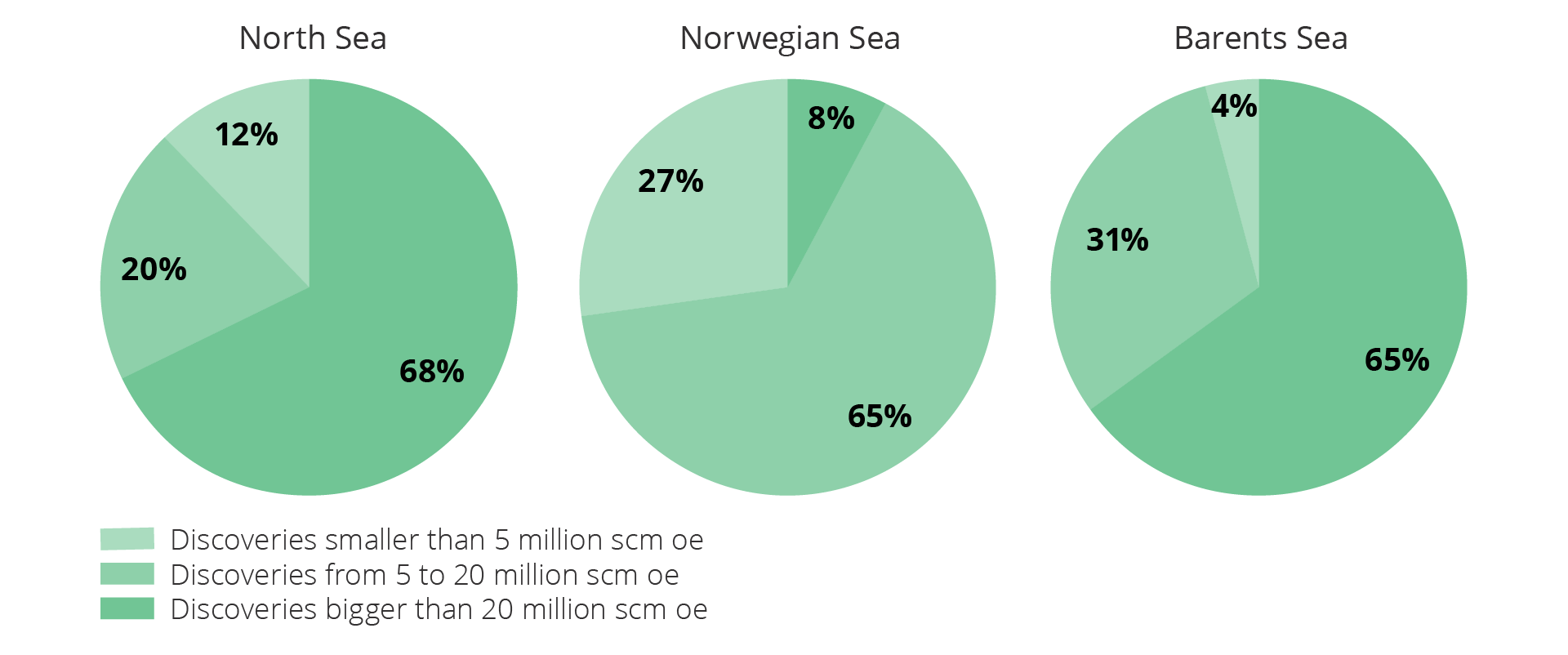

Exploration activity will remain at the current level over the next few years and will then decline. Over the short and intermediate term, the North Sea and Norwegian Sea will see the most exploration activity. These areas feature access to infrastructure with available capacity, and this can contribute to short lead times from discovery to production and short repayment times.

Discoveries being developed will maintain capacity utilisation on host fields, pipelines and process plants. Unit costs will be contained. This will increase profits on existing fields and result in a lower threshold for initiating new projects.

Over the intermediate and longer term, an increasing share of wildcat wells will be drilled in the Barents Sea, while the share in the North Sea will decline.

Many discoveries will be made, but they are consistently small and the resource growth from exploration will drop.

Technology development, discoveries and fields

As the industry is operated efficiently and extensive consolidation takes place, new discoveries will generally be profitable even if they are minor. Most new discoveries that come on stream will be developed as satellites to existing infrastructure, which will extend production on fields beyond original plans.

Several projects will be implemented to improve recovery on operating fields. However, these projects will not be sufficiently large to offset the production decline from operating fields.

The economy and society at large

The petroleum sector will account for substantial value creation over the next 25 years and will remain important for government revenues.

A report prepared by Statistics Norway (SSB) in 2022(17) estimates the number of direct and indirect jobs associated with the petroleum activities on the NCS at around 156,100 in 2021. This does not include jobs linked to the supplier industry's deliveries to the international petroleum industry. SSB presumes that jobs in the sector will decline in line with production. As production will drop by just under 70 per cent leading up to 2050, a similar reduction will be seen in jobs.

Alongside the decline in production, reduced activity, and production dropping by more than half leading up to 2050, there will also be a gradual decline in ripple effects on other industries. This will weaken the sector's role as the growth engine for the rest of the economy. At the same time, the industry in 2050 will still deliver substantial revenue per employee.

Low scenario

In this scenario, liquids and gas production will decline rapidly. This will accelerate the dismantling of the petroleum activities. A significant resource potential in fields, discoveries and undiscovered resources will never be realised.

Production development

Production will fall quickly from about 235 million scm oe in 2025 to close to zero production in 2050, see figure 4.7. In practice, this means that the petroleum activities will be dismantled.

Exploration activity and resource growth

Exploration activity will remain at the current level over the next few years, followed by a rapid decline. Most wells will be dry, few viable discoveries will be made, and exploration activity will stagnate.

Exploration wells drilled in the Barents Sea will be dry or result in very small discoveries. Exploration activity will therefore concentrate on the North Sea and Norwegian Sea, where ample access to infrastructure will incentivise further exploration. Nevertheless, as the discoveries will be very small, few of them will be developed. The exploration activity will therefore be unable to help maintain capacity utilisation on host fields, pipelines and process plants.

Technology development, discoveries and fields

Few new discoveries will be developed and very few improved recovery projects will be initiated. This will lead to a substantial production decline and reduced value creation for the industry.

Unit costs on fields will rise rapidly, as new discoveries through exploration will not contribute to substantially increased production on host fields. In turn, this will result in reduced profits and a drop in production. Costs will increase, accompanied by reduced profitability for exploration and the development of new discoveries. This will lead to many fields shutting down early.

The economy and society at large

The rapid decline in field production toward near-zero in 2050 will be accompanied by a reduction in both the number of jobs associated with the industry and ripple effects for the rest of the economy. SSB's calculations may indicate potential effects where the number of jobs drops by 100,000 compared with the base scenario(18).

In practice, this will entail a complete dismantling of the petroleum industry leading up to 2050. However, despite the substantial drop in production, this scenario will contribute to significant value creation over the next 25 years.

High scenario

Liquids and gas production will increase leading up to 2025 and stay at a high level over the next decade. Gas production will remain at a high level until 2037 and will then start to decline. The NCS is an attractive petroleum province, and the authorities and the industry both help maintain exploration activity, technology development and profitable petroleum production.

Production development

As of 2025, production will be maintained over the next decade, followed by a gradual decline. Production will drop from about 245 million scm oe in 2025 to about 120 million scm oe in 2050, see high, figure 4.7. In other words, production will be cut in half from 2025.

Exploration activity and resource growth

High exploration activity, both in areas close to infrastructure and more frontier areas, will quickly yield more and larger discoveries. Several major gas discoveries will be made in less mature areas in the Norwegian Sea early on in the period.

Multiple major discoveries will be made in the Barents Sea, for example in the western and central parts of the Barents Sea. These will be developed quickly. New and significant gas export capacity from the Barents Sea to the Norwegian Sea will be developed quickly. The major discoveries will lead to increased exploration. An increasing share of exploration wells will be drilled in the Barents Sea over the intermediate and longer term.

Increased exploration and more discoveries in mature areas will increase the value of existing fields and infrastructure. Discoveries being developed will maintain capacity utilisation on host fields, pipelines and process plants. Costs will be contained. Increased profits on existing fields will help extend production on the fields.

Technology development, discoveries and fields

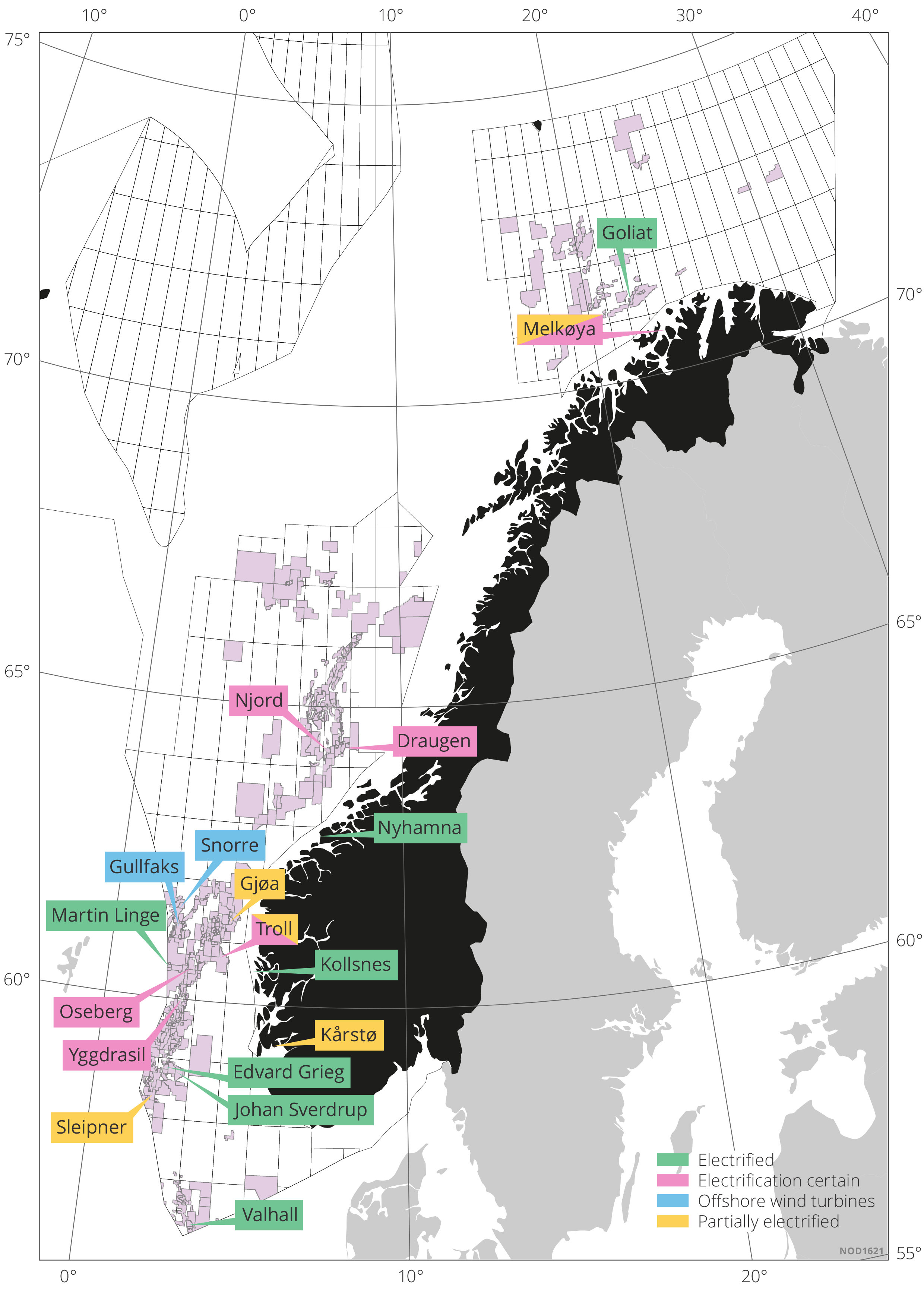

Multiple innovations will increase profitability for exploration, improved recovery and the development of new discoveries. A number of major discoveries will be developed, either as independent offshore solutions or as subsea tie-back solutions to onshore process plants. All new, independent developments will be supplied with nearly emission-free power.

Several projects will be implemented to improve recovery on operating fields. New technology will be developed and implemented quickly. This will aid in improving recovery from tight reservoirs as well. A number of players will attempt and succeed with advanced improved recovery methods.

The economy and society at large

The sector's importance for the Norwegian economy and government revenues will be significant in this scenario. As production will remain at a high level for 10-15 years, employment will be high and ripple effects for the rest of the economy will be extensive.

The sector's significance will decline toward the end of the period in line with tapering production. However, the industry will still enjoy substantial revenue per employee.

Consequences for future production and value creation

All three scenarios show a decline in production moving forward, but the pace of this decline varies across the three scenarios. The production decline will depend on development in the world at large, the resource base and the stakeholders' investments in exploration and technology developments.

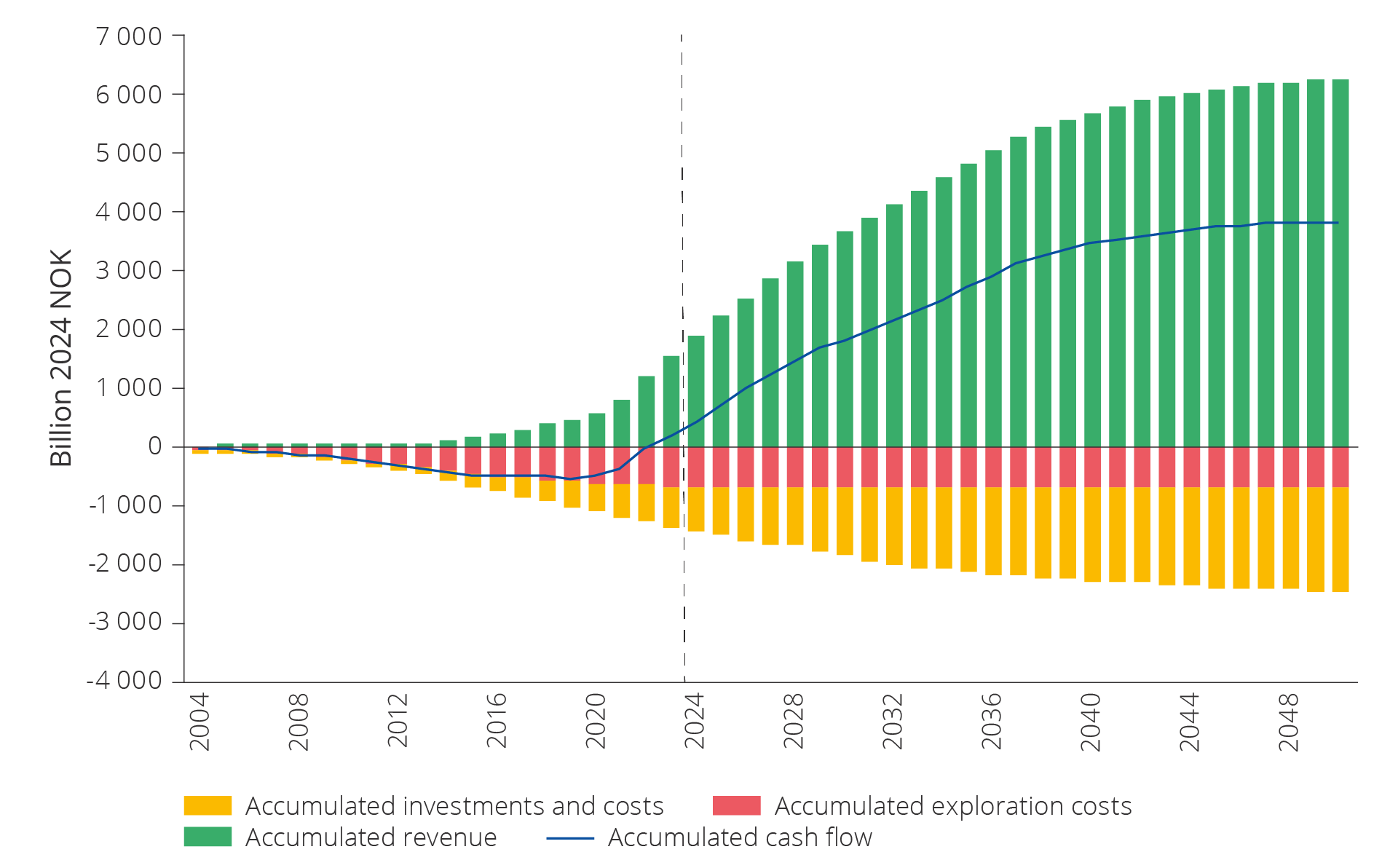

How these factors evolve could make a significant difference in future production. The three scenarios show a difference in accumulated production of 2400 million scm oe in 2050, see figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8 Projection of accumulated production leading up to 2050 in the three scenarios.

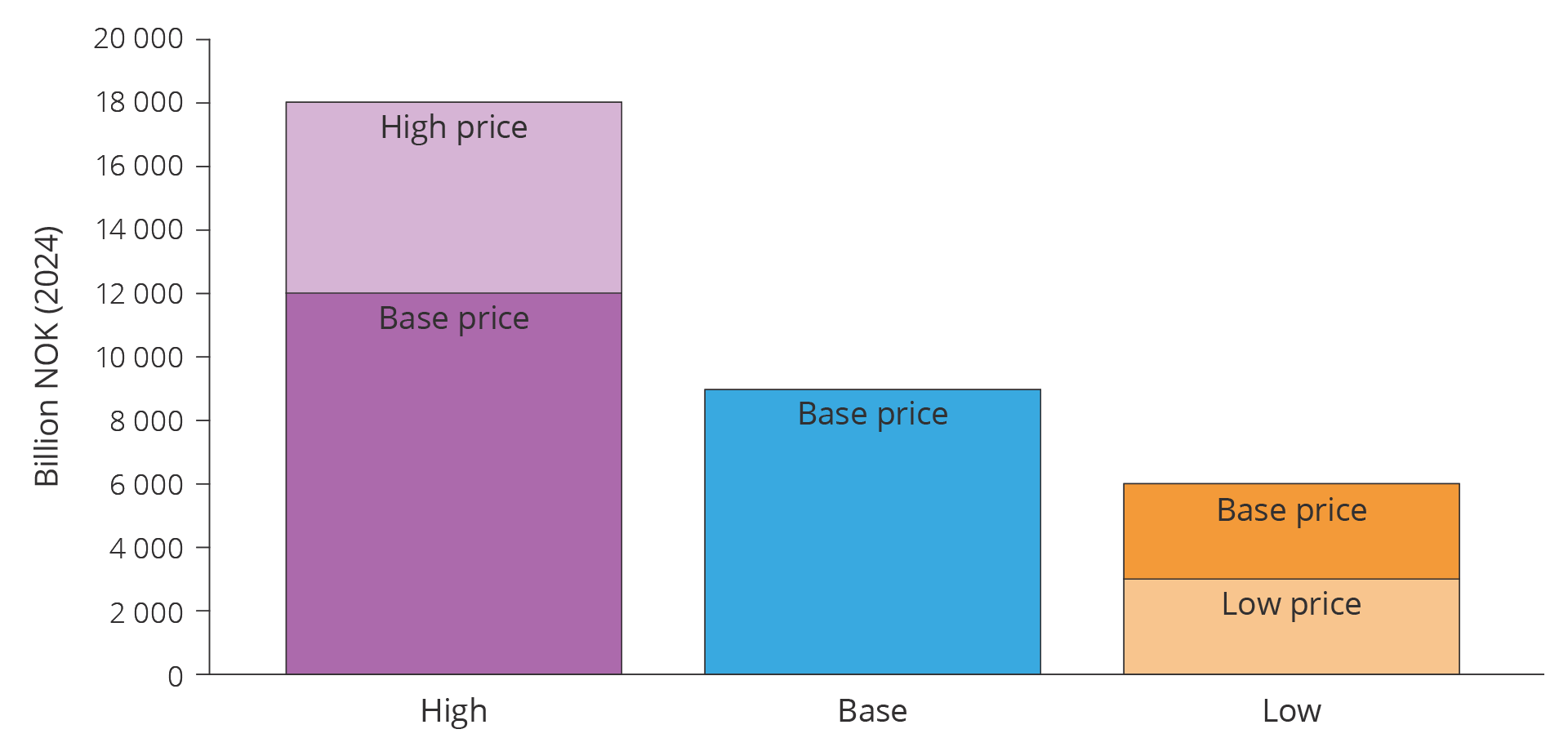

The scenarios reveal stark differences in future value creation and future government revenues from the petroleum sector, see figure 4.9.

Figure 4.9 Projection of net cash flow from Norwegian petroleum activities 2025–2050 in the three scenarios. One trajectory where all three scenarios have a basic price of USD 70/bbl, and one including price sensitivity of USD 95/bbl in high, and USD 45 in low.

The number of jobs, inputs and ripple effects are adjusted downward in line with the decline in production. Calculations conducted by SSB(19) show that adaptation costs associated with the transition to different commercial activities are uncertain, despite the changes taking place over a longer period of time, such as in the base scenario. These costs could be substantial in the event of a rapid dismantling as seen in the low scenario(20). At the same time, there is significant uncertainty associated with the future activity level, even within each scenario.

Measures to increase resource growth and keep unit costs low will be crucial for future production and future revenues in all scenarios. New industries may help bolster the established value chains in oil and gas.

DownloadRemaining resources

In this chapter:

- Managing the petroleum resources

- Reserves and challenges in fields

- Several measures can yield improved recovery

- Resources and challenges in discoveries

- Exploration builds the foundation for long-term production

One of the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's most important responsibilities is to maintain an overview of the remaining petroleum resources, in order to ensure that the authorities and players have the best possible factual and knowledge basis. This contributes to learning, sound resource management and good decisions that can help to maintain exploration activity and production over the years to come.

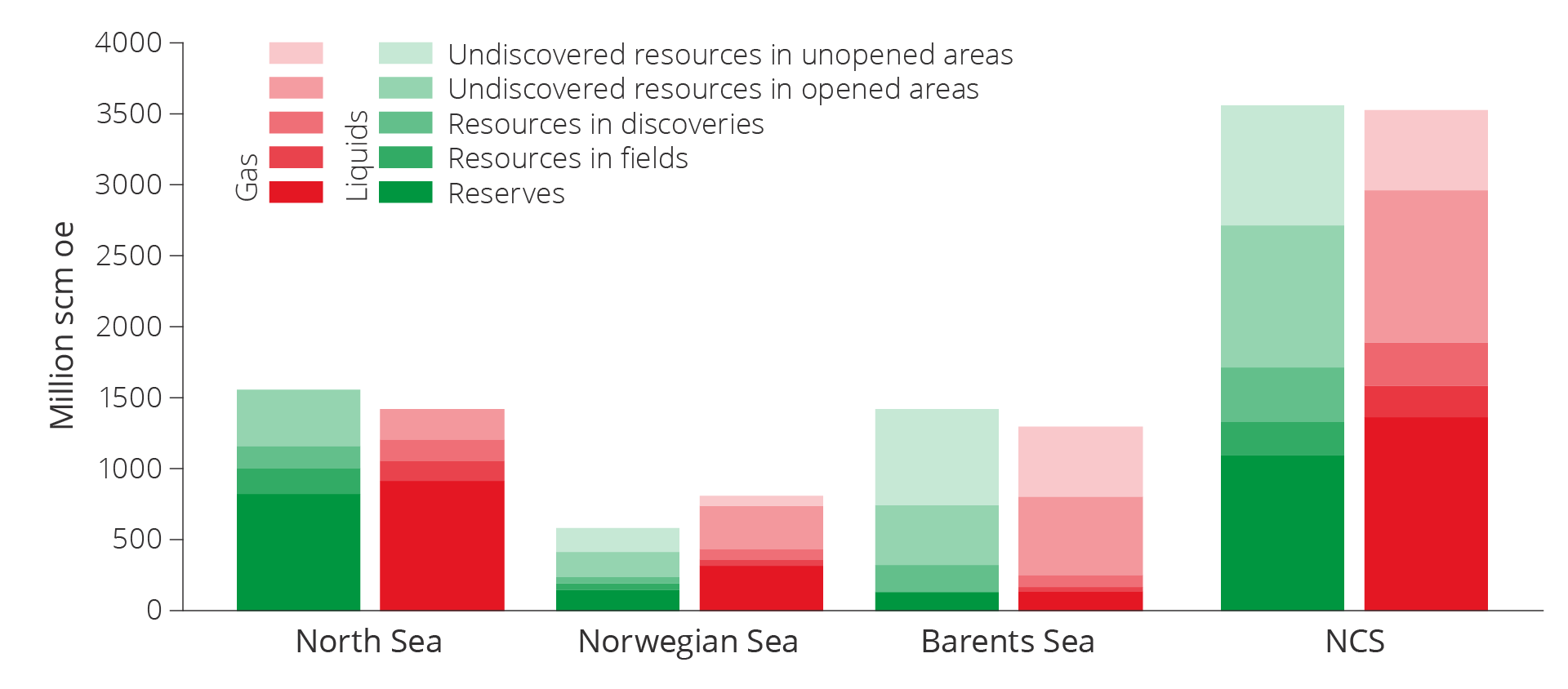

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's estimate of the total remaining resources on the NCS is about 7.1 billion scm oe. Of the remaining resources about 3.6 billion scm oe are reserves and resources in discoveries and fields, while about 3.5 billion scm oe are undiscovered resources. About 60 per cent of these resources are in opened areas.

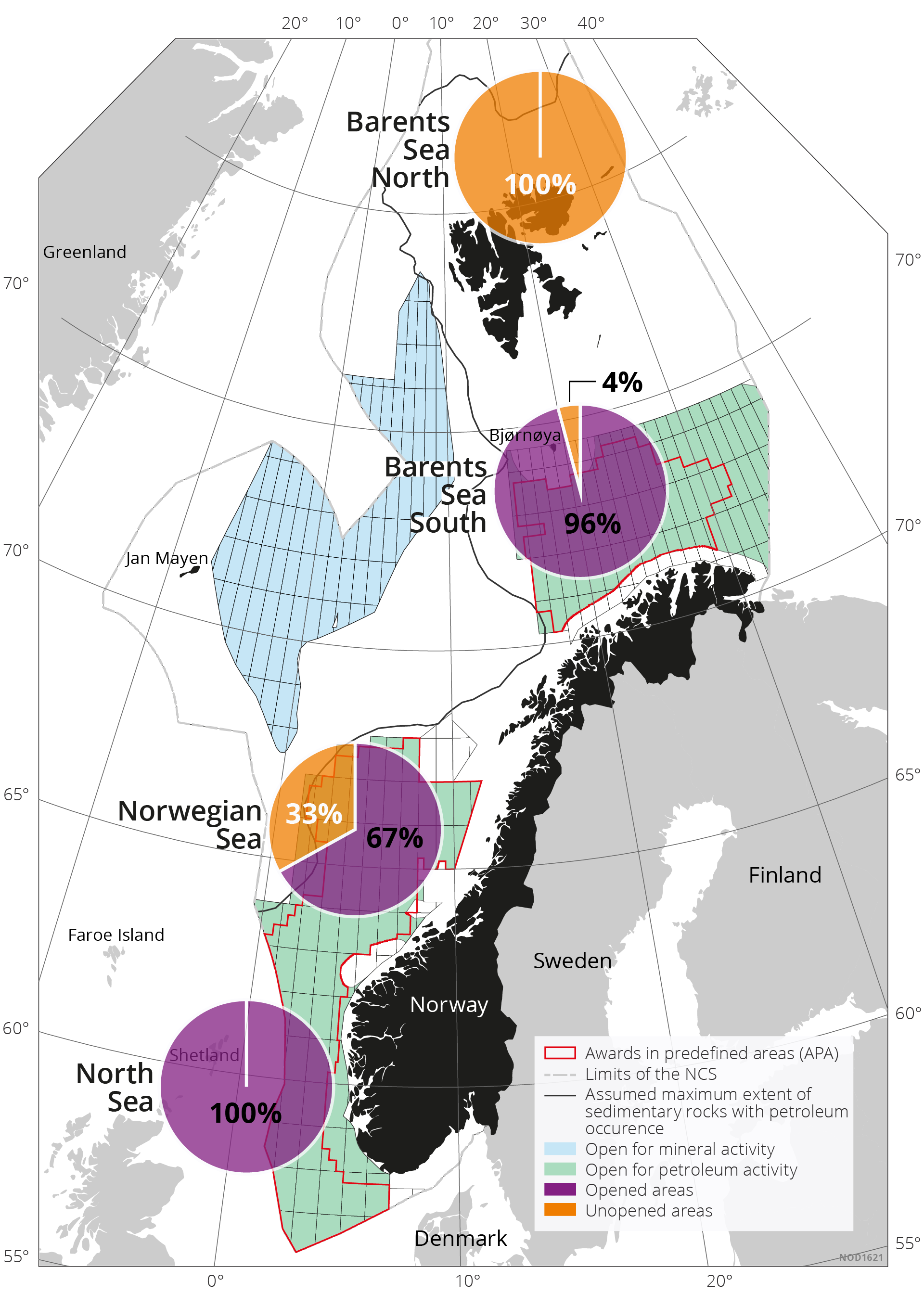

Figure 5.1 shows the remaining resources and distribution between discovered and undiscovered resources in opened and unopened areas, respectively, for the three regions.

Figure 5.1 Total remaining petroleum resources distributed between liquids and gas, resource classes and regions on the NCS as per 31 December 2023.

Since it has been the centre of activity the longest, most experience and information is from the North Sea. Here, the majority of liquids and gas, about 60 per cent, is defined as reserves. This means that they are subject to approved recovery plans; see resource classification in chapter 3.

In the Norwegian Sea, undiscovered resources account for just over 50 per cent of remaining resources.

Undiscovered resources also account for the largest share in the Barents Sea. About 80 per cent of the remaining liquids and gas resources in the Barents Sea have yet to be discovered. Large areas in the Barents Sea remain closed for petroleum activity, and these areas are presumed to be home to about 50 per cent of the undiscovered resources in the Barents Sea.

The total remaining resources constitute a basis for oil and gas production for many years to come, as highlighted in figures 3.6 and 4.3.

In order for the NCS to maintain production at a high level, it is important that the companies invest to curtail the expected decline in production. The authorities acting as a driving force for comprehensive and long-term solutions can serve as a guarantee for decisions that contribute to sound resource management.

Managing the petroleum resources

The Petroleum Act(21) stipulates that the Norwegian State has the proprietary right to subsea petroleum accumulations and the exclusive right to resource management. Resource management of petroleum resources shall be carried out with a long-term perspective for the benefit of the Norwegian society as a whole.

Oil and gas resources are not renewable, and the activities are capital-intensive and take a long-term perspective. This is why one of the authorities' primary missions is, as resource owner and regulator, to establish and maintain a framework for the activities. This framework shall help ensure that the oil companies have a self-interest in utilising oil and gas resources in the best interests of the broader society.

However, the companies' and society's financial assessments do not always align(22). This is called market failure(23). These are instances where government measures may help ensure that resources are put to better use for the broader society. The fact box below shows selected examples of market failures that may occur in the petroleum sector, and which create a need for government measures.

Regulation of the petroleum activities seeks to take into consideration the most important forms of market failure and is designed to yield the best possible overlap between the companies' decisions and the authorities' interests.

Market failure in the petroleum sector

Market failure comes in different varieties in the petroleum sector. The authorities regulate, correct or influence the companies' decisions to ensure that they coincide with what is best for the broader society. The most common forms of market failure within the petroleum activities are described below.

Public goods(24) or shared goods are goods with the following properties:

1) Non-exclusivity, which means that no-one can be prevented from consuming the good; and 2) non-rivalry, which means that one person's consumption of the good does not diminish another person's consumption of the same good. When it is not possible to exclude others from using the good, it is difficult to establish a market for this good. No-one will be willing to pay for a good they have access to regardless. Neither will anyone be willing to invest in a good that everyone will have access to.

The value of the public good for society exceeds the companies' willingness to pay. This means that authority intervention to ensure that public goods can be produced may be in society's best interest.

One example is publicly available data and information about the geology on the NCS. Another example is government support for research and development (R&D). If the authorities do not take an active role, there will be insufficient research and not enough geodata will be collected. It is also important that the authorities, as resource owner, are as familiar as possible with the opportunities in place on the shelf(25).

Positive external effects are advantages from a company's activity or investments, which the company does not take into account in its decisions. Examples include investments in R&D or exploration that generate new knowledge. Others will benefit from this knowledge without the company receiving compensation. This could indicate regulation and/or government support.

Increased R&D efforts or exploration can also be stimulated through other types of policy instruments, such as patents or disclosure rules associated with sharing geological information. Such arrangements ensure that the party that develops a new solution or makes a new discovery is protected from early imitation efforts and others enriching themselves on the basis of their ideas. The disadvantage here is that this prevents the dissemination of important information or technologies.

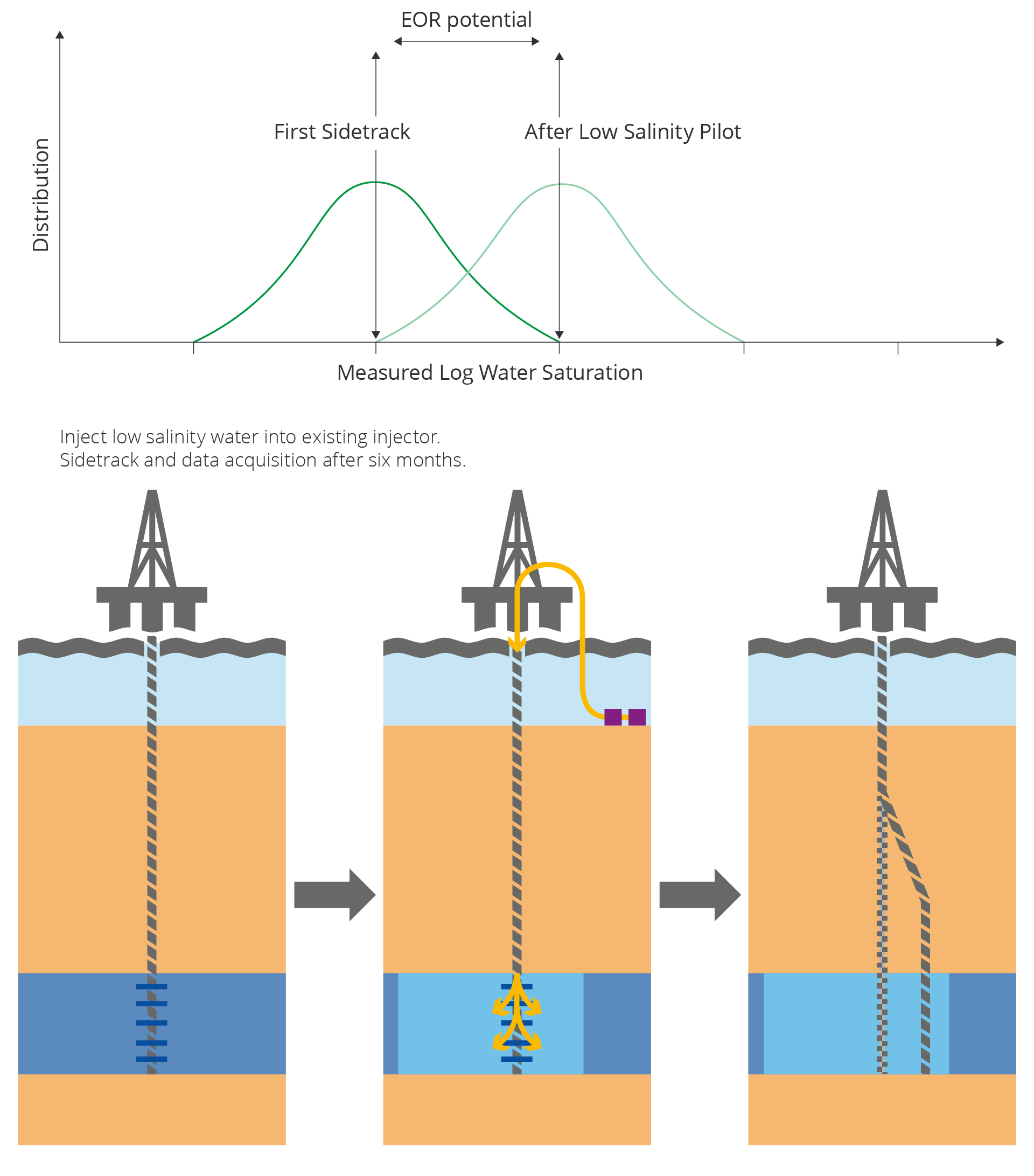

Testing new technology, such as an EOR pilot (enhanced oil recovery), is also a variant of positive external effects. Technology tested by licensees in a production licence has positive effects for other production licences.

Network effects: Positive network effects will arise when a company's purchase of a good increases the benefit for all other buyers of this good. This can be a direct effect: The more users of a video-conferencing platform, the better this will be for all users of the platform. It can also be an indirect effect. One example is carbon capture from power plants and industry where the benefit for the individual company depends on access to infrastructure to transport and store CO2.

The point is that a company will benefit from other companies using the same type of technology. Positive values will be created beyond what the individual company will take into account. If the new technology is socio-economically profitable, this indicates that the government, during a transitional period, can take a coordinating role and contribute to ensure the establishment of an adequate number of users of this technology. One example of this is awarding storage opportunities for CO2 that can accelerate the capture and transport of CO2.

Negative external effects: Petroleum activity has disadvantages that the oil companies are not necessarily incentivised to take into account in their profitability calculations. This could involve pollution to sea, the seabed and coastal zone, as well as greenhouse gas emissions and other emissions to air.

If the oil companies are not held accountable for the socio-economic cost of their emissions, this will entail higher emissions than what is socio-economically acceptable. This can be avoided by employing environmental taxes and credit trading, thus ensuring that the companies include the societal disadvantages in their own cost assessments.

Petroleum activity can also lead to disadvantages for other commercial activity.

Lack of ownership of petroleum resources in the vicinity of their own production licences can entail that the companies' proposed solutions are not necessarily in the best interest of society. For example, this could result in the companies disregarding coordinated developments that would yield economies of scale and thus lower overall development costs.

A lack of area perspective and coordination across licence boundaries can also be caused by the players having different information about resources and costs. Different access to information relevant for decision-making can create a basis for different adaptation and strategic behaviour that could prevent profitable projects from being implemented.

Imperfect capital markets: Lack of or asymmetrical information about profitability in projects can also result in potential lenders not giving access to sufficient capital. In a capital market, the lender will generally have less information about profitability factors and creditworthiness than the borrower. This means that an investor or creditor could assess the risk as higher than it actually is, which leads to high interest rates or rejected loan applications. This can also contribute to less exploration and R&D than what is best for the broader society.

Economies of scale and market power: Both fields and transport infrastructure have economies of scale, which means that unit costs will falls alongside increasing production capacity. It is efficient to coordinate production and transport in order to utilise the advantages of large units. One disadvantage here is that large units can utilise their size and market power e.g. by demanding high prices for processing and transport. In such instances, there may be a need for government regulation. In the petroleum sector, this regulation takes place through regulated access to gas infrastructure and through the TPA Regulations (Regulations relating to the use of facilities by others).

Lack of long-term perspective in the licensees' decisions can entail that the companies have higher required rates of return than what is used in socio-economic analyses. Required rate of return means the minimum compensation the company needs to invest in a new project. The company will require higher return for high risk and lower return for low risk. The State will usually perceive the risk as lower than the companies since the State owns more projects with variable risks. Future opportunities will be valued lower by the companies than the State due to the higher required rate of return, for example exploration opportunities.

Absolute profit requirements: Internal capacity restrictions in the companies or restrictions in other markets such as capital or labour markets can result in an absolute profit requirements in projects. One such requirement could be a minimum requirement for the project's net present value after tax. This could lead the companies to de-prioritise socio-economically profitable projects on the NCS because they have projects with higher profitability in other petroleum provinces.

All these factors could cause the companies' decisions to lead to solutions other than what most benefits the broader society. This could result in lower exploration, fewer improved recovery projects and lower production than what is socio-economically profitable.

The companies' decisions and possible market failures can be linked to different phases, from exploration to decommissioning. In this chapter, these decisions concerning remaining resources, are split between the resource categories reserves, resources in fields, resources in discoveries and undiscovered resources.

Reserves and challenges in fields

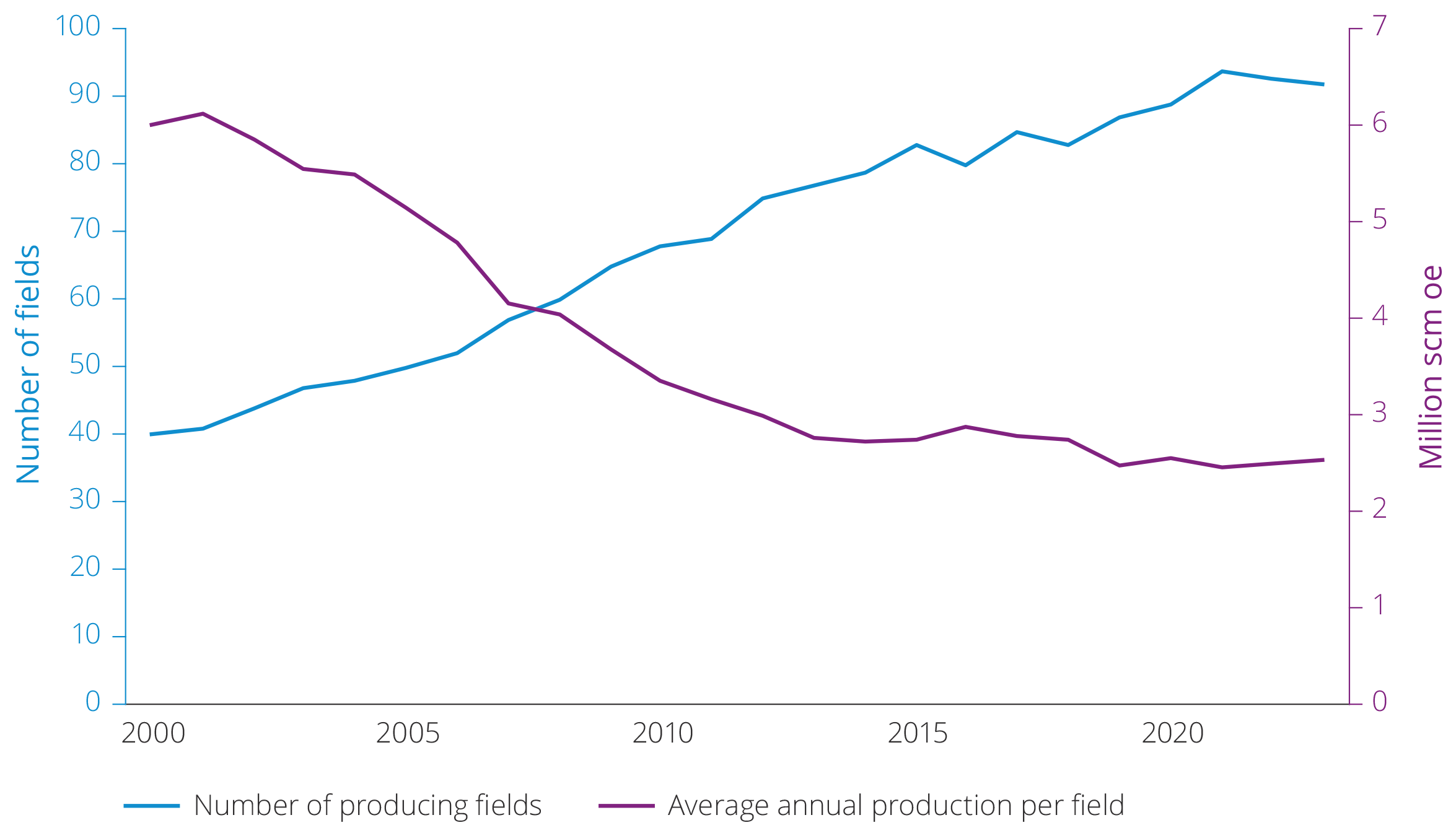

At the start of 2024, there were 92 producing fields; 67 of which were in the North Sea, 23 in the Norwegian Sea and 2 in the Barents Sea.

Petroleum production on the NCS maintained a stable, high level in 2023. Oil production was at the highest level since 2010, while gas production declined somewhat from record-high levels in 2022.

The production of petroleum has increased each year since 2020 as shown in figure 5.2. Petroleum production is expected to increase in 2024. According to estimates, the level in 2025 will be the highest since 2006.

Total production from reserves in existing fields is expected to decline after 2025, in line with depletion and pressure drop in reservoirs. Based on current knowledge, production from operating fields is expected to drop by more than half during the period through and including 2033.

Figure 5.2 Remaining reserves. Historical total production 2019-2023 and expected future production from reserves 2024–2033.

A number of plans for development and operation (PDOs) were submitted to the Ministry in 2022 and processed in 2023, illustrated in figure 3.3 and described in the fact box on plans for development and operation (PDOs). All of these plans were approved by the authorities and are now included in expected future production from reserves in figure 5.2.

This major increase in the number of PDOs in 2023 was primarily caused by the temporary changes in the petroleum tax, further described in the fact box on the temporary changes to the Petroleum Tax Act adopted in June 2020. These changes in taxation have facilitated the realisation of more developments, with earlier production than would otherwise have been the case. These development projects will help ensure that production can remain relatively high over the next few years. Several projects are also facilitating power from shore, in order to reduce CO2 emissions from production.

Figure 5.3 Approved plans for development and operation (PDOs) and PDO exempts in 2023.

Plans for development and operation (PDOs)

Before licensees can develop one or more discoveries, the authorities need to approve a plan for development and operation (PDO).

A PDO consists of a development part, which covers the development of the discovery or discoveries, and an impact assessment part, which covers the impacts the development will have. Developments can be exempted from the submission of a PDO.

This will primarily be relevant for developments of minor discoveries that can be reached from existing facilities on fields with an approved plan for development and operation. A discovery developed in this manner will normally be incorporated into the existing field without being given a separate name.

Temporary changes in the Petroleum Tax Act

In June 2020, the Storting (Norwegian parliament) passed temporary amendments to the Petroleum Tax Act, cf. Proposition No. 113 L (2019–2020) and Recommendation No. 351 L (2019–2020).

The objective was to help ensure that the oil companies could continue to work on planned investment projects despite temporary liquidity, funding issues and increased uncertainty surrounding the future due to the pandemic and its impact on the energy markets.

The background was that investment activity on the NCS was projected to be lower than expected before the pandemic as a result of planned investment projects being delayed. Such delays could have increased the risk of shutdowns and bankruptcies in the supplier industry.

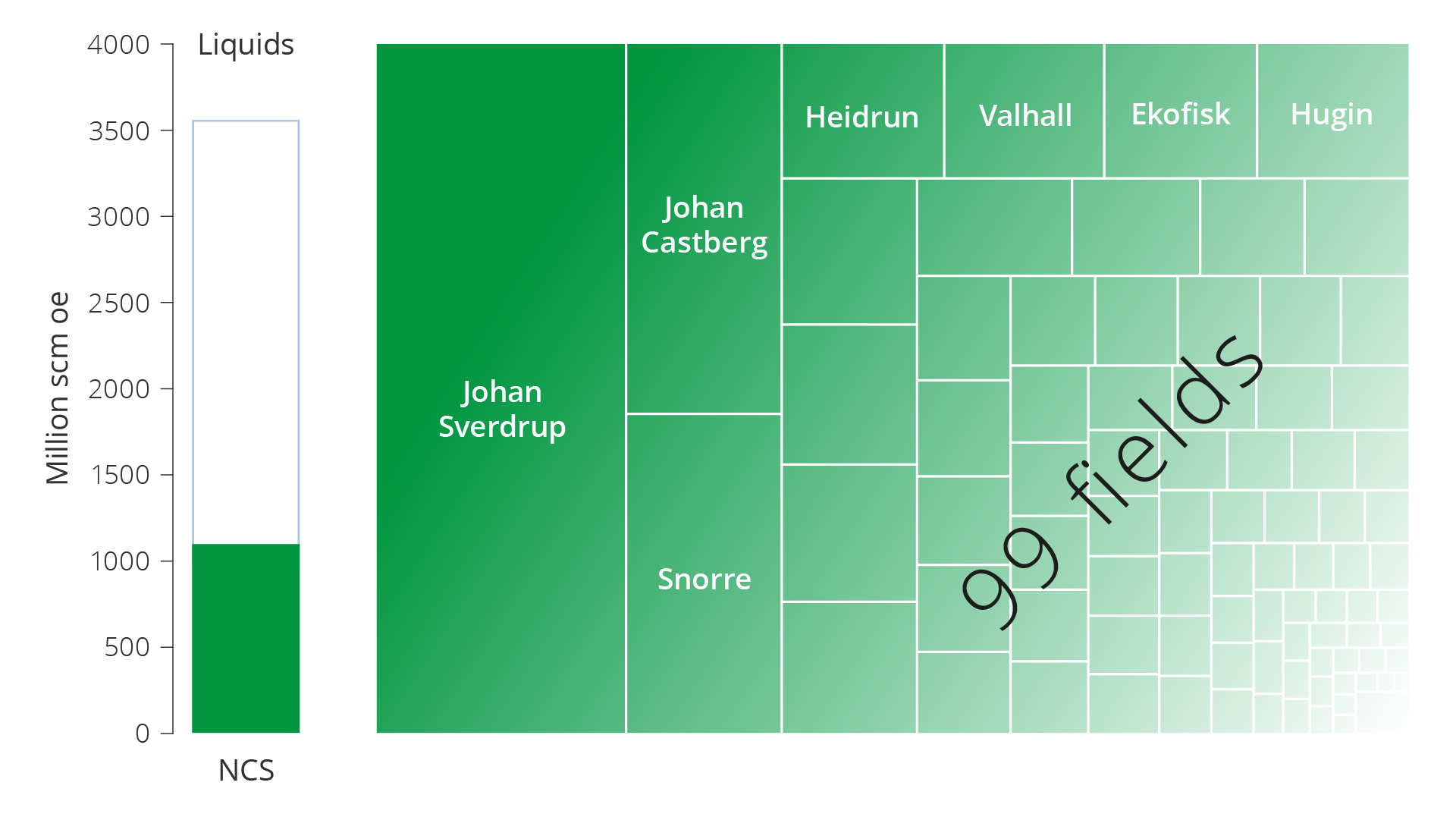

Considerable remaining quantities of liquids

The remaining quantities of liquids on the NCS are still considerable. About 60 per cent of overall expected liquids resources have been produced since Ekofisk came on stream in 1971. Remaining liquids reserves distributed across fields are shown in figure 5.4. Johan Sverdrup (24 per cent) is the field that clearly has the most remaining reserves and which produces the most oil annually.

The second largest is Johan Castberg (8 per cent), which is expected to come on stream in 2024. Snorre accounts for 7 per cent. Yggdrasil with the Hugin, Munin and Fulla fields and expected start-up in 2027, will collectively account for 6 per cent of the overall remaining reserves.

Figure 5.4 Remaining liquids reserves on the NCS as of 31 December 2023. Percentages are distributed across fields.

Liquids production will also decline in the future in several fields containing both, oil and gas as a result of initiating gas blowdown.

Gas blowdown

In some fields, which contain both oil and gas, the oil is produced first. This prevents the pressure from dropping in the reservoir, which will complicate extraction of the underlying oil. Eventually, as there will be less oil to produce, the field can start producing the gas in a so-called gas blowdown.

Several fields that have been injecting gas for improved oil recovery have halted this injection in recent years. For many fields, halting injection in this manner can be the first step towards gas blowdown on the field, and thus increased gas production. Examples of fields that have halted their gas injection include Visund and Gina Krog.

A full blowdown cannot start until active measures are taken to produce the gas in the gas cap. This can be done by drilling new gas production wells into the gas cap, converting gas injection wells into gas production wells or by opening gas cap zones in the existing oil production wells.

Once gas injection ends and gas production increases, most fields will see a minor increase in oil production, but in most instances, total oil recovery would have been higher if gas injection had continued.

Injection normally ends when the gas blowdown starts. The combination of stopping injection and increasing gas production will result in a rapid pressure drop in the reservoir. This is why it is important to conduct studies which ensure an adequate number of wells, so that all profitable oil resources in the field can also be produced.

Gas blowdown can also take place by lowering the pressure in the reservoir to the point that the gas, which was originally dissolved in the oil, condensates and can be produced. This is done on the Statfjord field, where the depressurisation started in 2007.

Market failure and accelerated gas blowdown

With high gas prices, it can be profitable to accelerate the gas blowdown timeframe by stopping gas injection and switching to gas export. The consequence of this will be a reduction in reservoir pressure and the end of oil production. Early gas blowdown can also affect oil production in neighbouring fields if the reservoirs are in pressure communication.

Such accelerated gas export will result in revenues and costs, that are taken into account in both a traditional commercial and socio-economic analysis. The profitability of this decision will be affected by the fact that accelerated gas export is an irreversible decision that could result in profitable oil being permanently stranded.

As long as the gas is re-injected, the companies have the opportunity to either continue oil production or start exporting gas. If the companies export the gas, parts of the known oil accumulations will be unavailable for production and sale.

Differences between profitability assessments made by the companies and the broader society could result in the companies setting lower future valuations than the authorities. Since the gains in the form of improved oil recovery are long-term, some licensees could potentially want to produce the gas faster than what would be in society's best interest. The higher required rate of return, the less attractive it could be to extract the remaining oil before gas production starts.

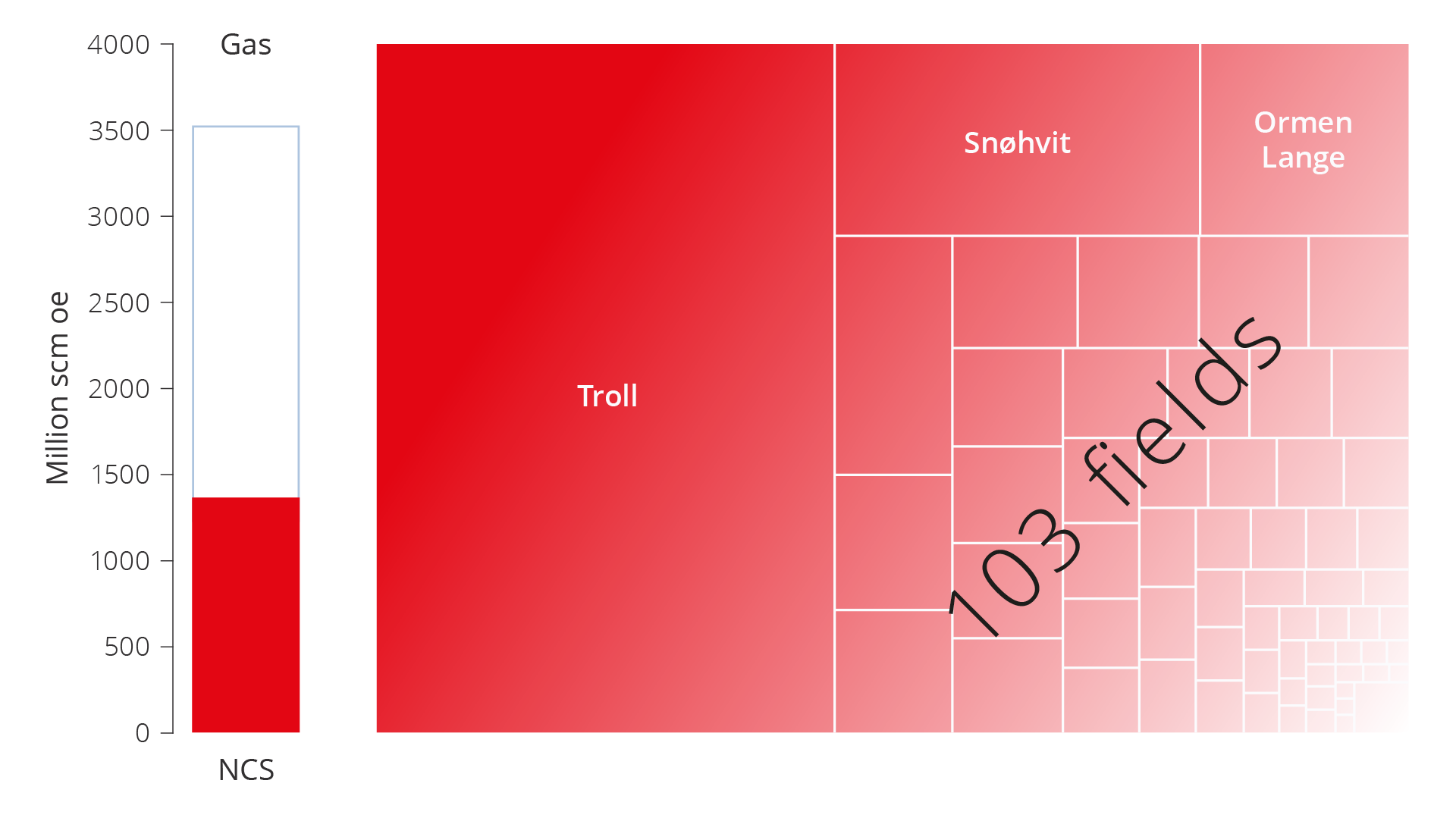

Large remaining quantities of gas

About 45 per cent of total expected Norwegian gas resources have been produced since gas exports from the NCS started in 1977. Remaining gas reserves distributed across the fields are shown in figure 5.5. Located in the North Sea, Troll (44 per cent) is clearly the field with the most remaining gas reserves. It is followed by Snøhvit in the Barents Sea with 10 per cent and Ormen Lange in the Norwegian Sea with 6 per cent.

Figure 5.5 Remaining gas reserves on the NCS as of 31 December 2023. Percentages are distributed across fields.

117 billion scm of gas were exported in 2023. The Troll field produces the most gas, and in 2023 it accounted for 32 per cent of Norwegian gas production. When Troll eventually comes off plateau, there are no other fields or discoveries large enough to offset this decline.

The Troll field has two main structures: Troll Øst and Troll Vest. About two-thirds of the recoverable gas reserves are located in Troll Øst. Production from Troll Øst has evolved over a number of years with the installation of compressors on Troll A and pipelines to shore. Gas production from the first development stage of the Troll Vest gas province started in 2021.

In 2024, the Troll licensees decided to accelerate gas production from Troll Vest. This will be done by installing two new well templates with a total of 8 new wells and a pipeline back to Troll A. According to the licensees, this project will accelerate about 55 billion scm of gas starting from 2026. At its peak, this will amount to 7 billion scm in a single year. This is the equivalent of about 80 TWh or about one-half of Norwegian power generation in 2023.

Several measures can yield improved recovery

There are multiple improved recovery measures that can contribute to realising parts of the resources that, as of 31 December 2023, are expected to remain after the field is shut down. These measures can help slow the decline in production.

The expected estimate for contingent (no decision to develop) liquids resources in fields is about 355 million scm, and 290 billion scm for gas. These resources are periodised in figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6 Remaining reserves and resources in fields. Historical total production from 2019–2023 and expected future production from reserves and resources in fields for the period between 2024–2033.

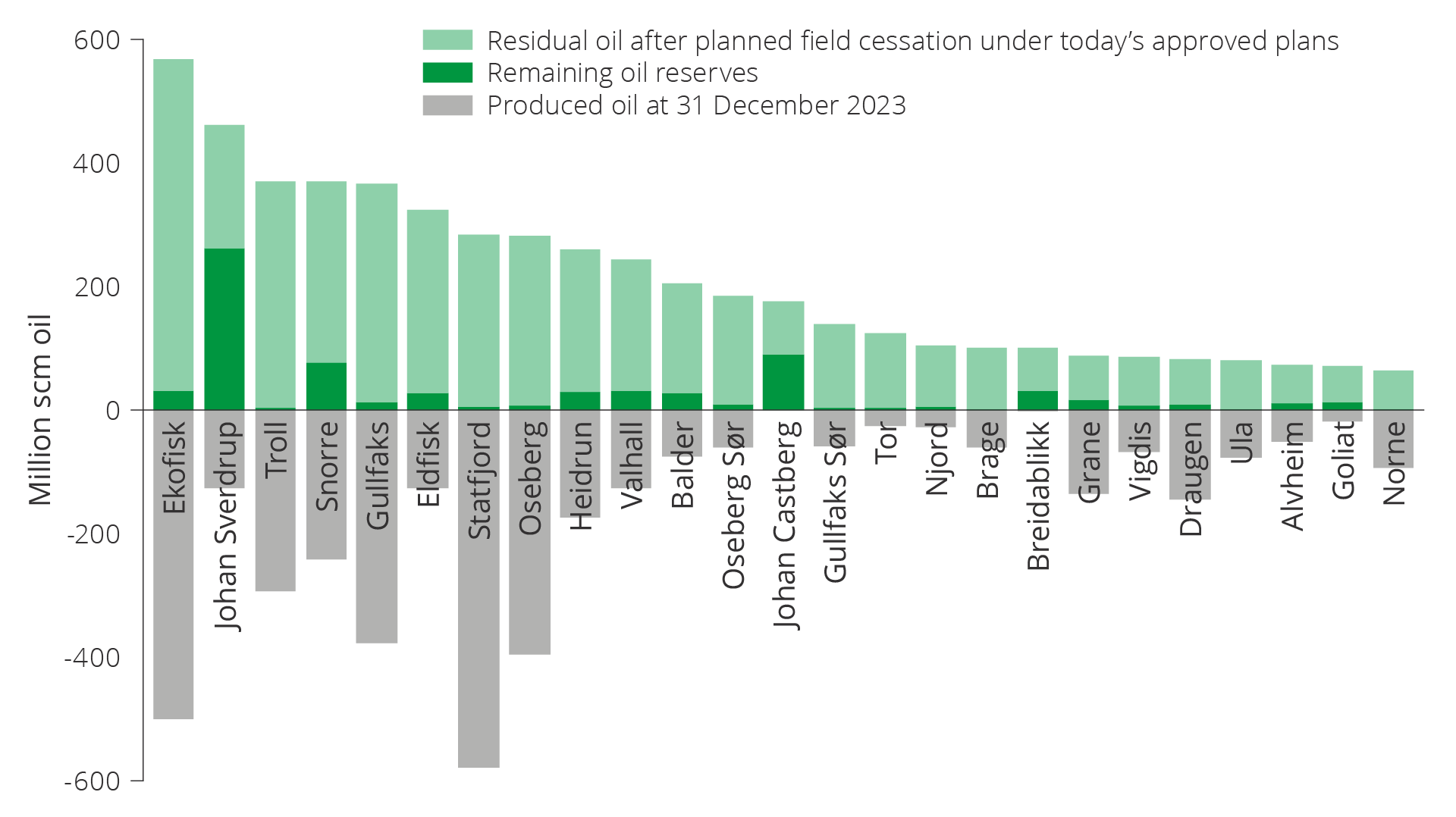

Many fields contain large volumes of oil beyond what is planned for production, and these fields are expected to shut down with considerable quantities oil stranded in the reservoirs. If some of this oil is produced before the field shuts down, production can be maintained for a longer period of time, and considerable value can be realised. Figure 5.7 shows produced oil, remaining oil reserves and remaining oil after planned production cessation for the largest oil fields as of 31 December 2023.

Figure 5.7 Remaining oil reserves, remaining oil after planned production cessation according to current plans and produced oil as of 31 December 2023.

Reported projects for improved recovery

The licensees are working continuously to map the resource base, drill new wells and implement other improved recovery measures on operating fields.

The projects the companies have reported to the authorities in connection with reporting for RNB 2024 (revised national budget) comprise 171 specific, but not yet approved projects for increased petroleum production and lifetime extensions.

Improved recovery measures on the fields

Wells are new development wells (injection and production wells) on the fields that are planned to be drilled from existing slots on fixed facilities or seabed templates.

Further development covers various measures to further develop fields, often by installing new infrastructure, for example seabed templates to add additional well slots for drilling or new pipelines. This category also includes projects to re-develop fields that are no longer producing, and projects to replace the fields' power supply. Further development projects will often need to be assessed by the authorities.

Late-phase production is production at the tail end of a field's lifetime. Late-phase production is reported separately from other production, since there is considerable uncertainty associated with this. The uncertainty could be the facilities' technical lifetime or the profitability of production.

Low-pressure production mainly includes projects where the installation's inlet pressure is reduced, thereby increasing the production rate from reservoirs with lower pressure. Low-pressure production leads to reduced process capacity on the installation if no investment is simultaneously made for compression on the seabed or on the installation. Compression helps ensure that the pressure in the process plant remains the same, see also low-pressure production, Chapter 6.

Injection and advanced methods cover a broad spectrum of measures. This could be increased or optimised injection of, for example, water and/or gas. Using technologies to fracture tight reservoirs is another example of this type of project, see Chapter 4, EOR.

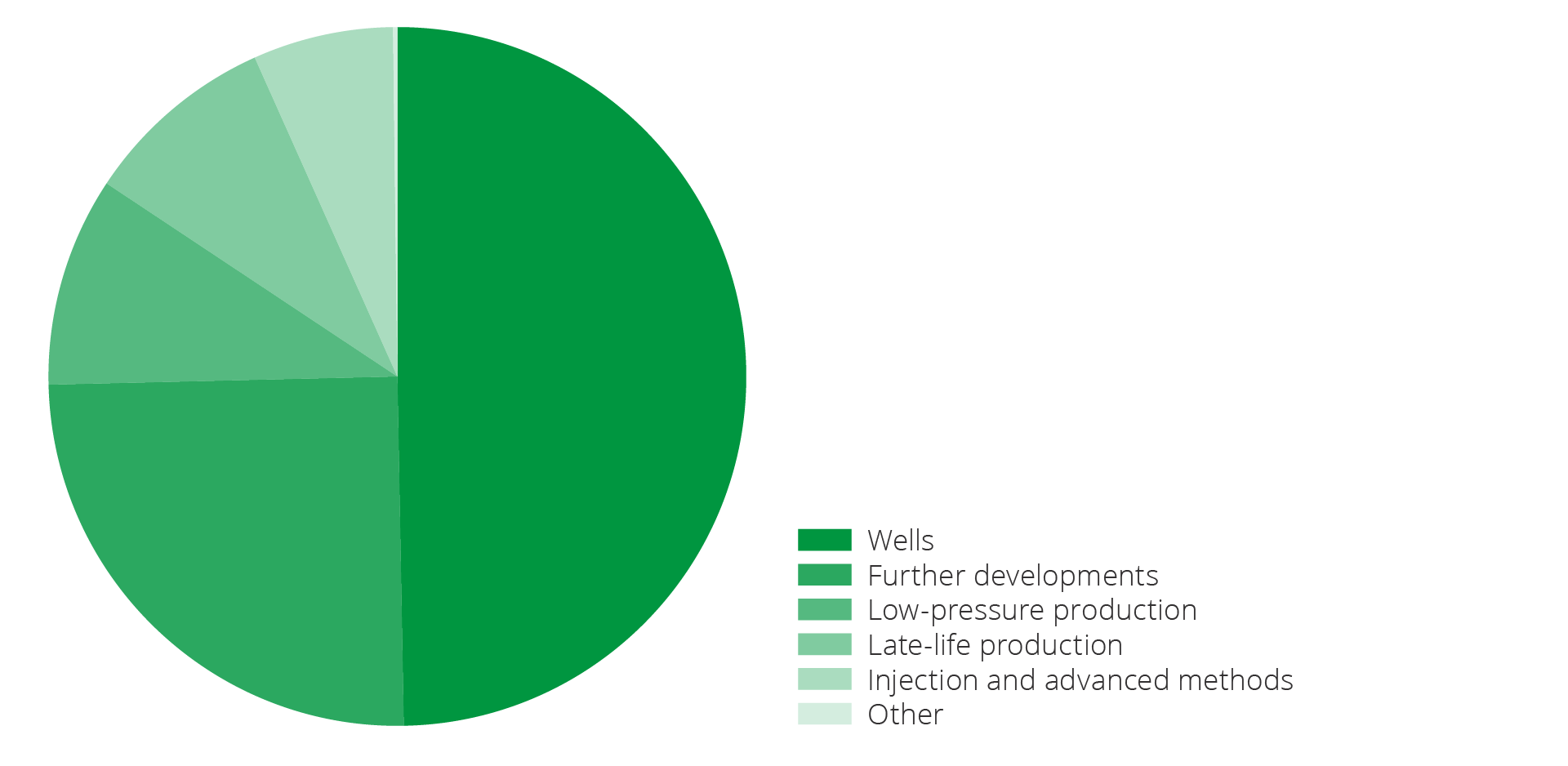

It is important to implement new technology, in order to realise new projects for the fields. Figure 5.8 illustrates the reported, but not yet approved, measures that could contribute to enhanced recovery of liquids. In total this will result in increased recovery of approximately 155 million scm oe of liquids, if the projects are implemented. Drilling new wells is the measure that represents the single largest contribution to improved recovery, while further development accounts for one-fourth of increased liquids resources.

Figure 5.8 Potential measures reported in 2023 for increased recovery of liquids from fields, distributed across different project types. In total, this amounts to about 155 million scm oe of liquids.

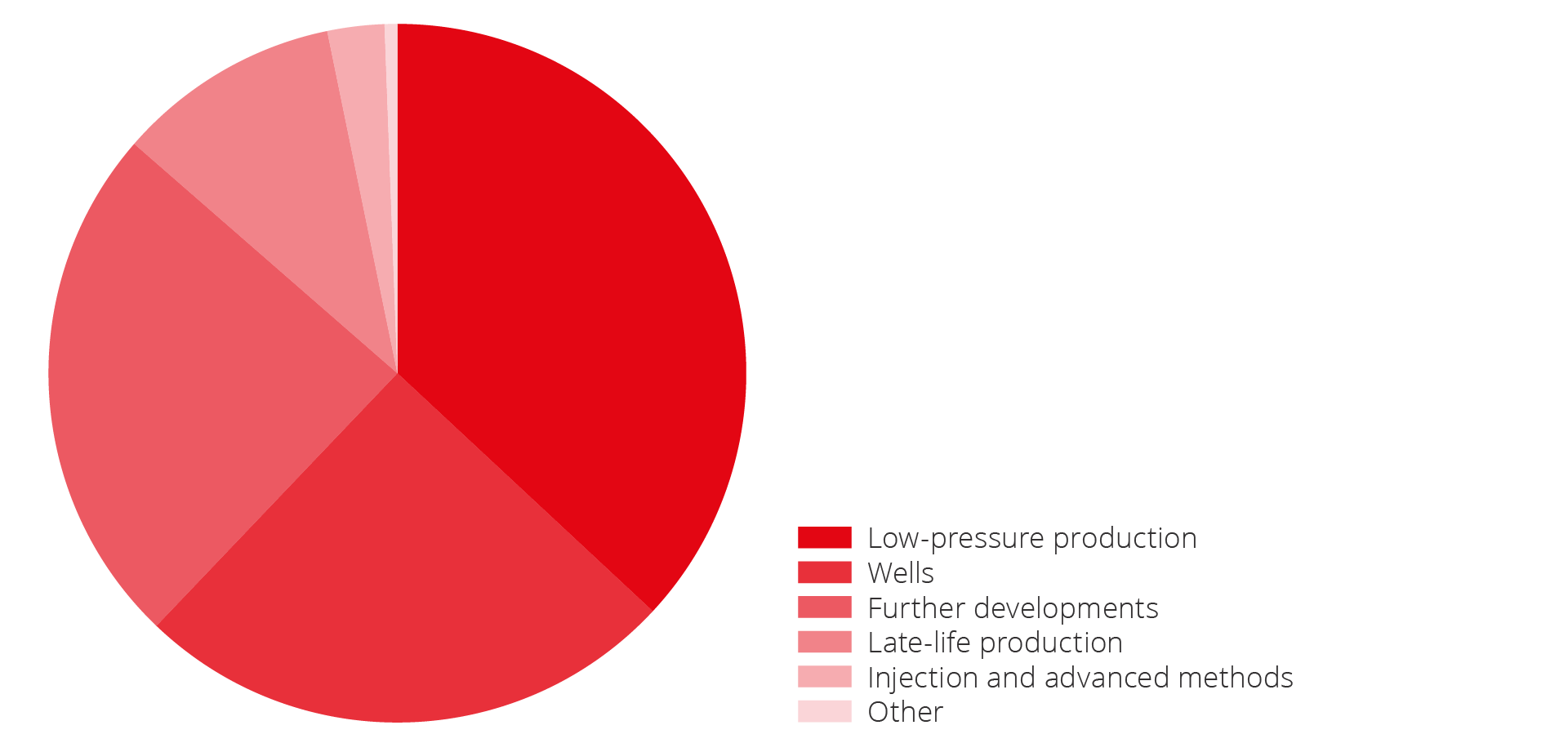

Figure 5.9 shows reported, but not approved measures that can contribute to improved gas recovery. Overall, this can result in approximately 170 billion scm of gas if implemented.

The measure that provides the greatest contribution for improved gas recovery is low-pressure production, followed by wells and further development. There are very few reported projects within injection and advanced methods.

Figure 5.9 Potential measures for improved gas recovery from fields distributed across different project types. In total, this amounts to about 170 million scm oe of gas.

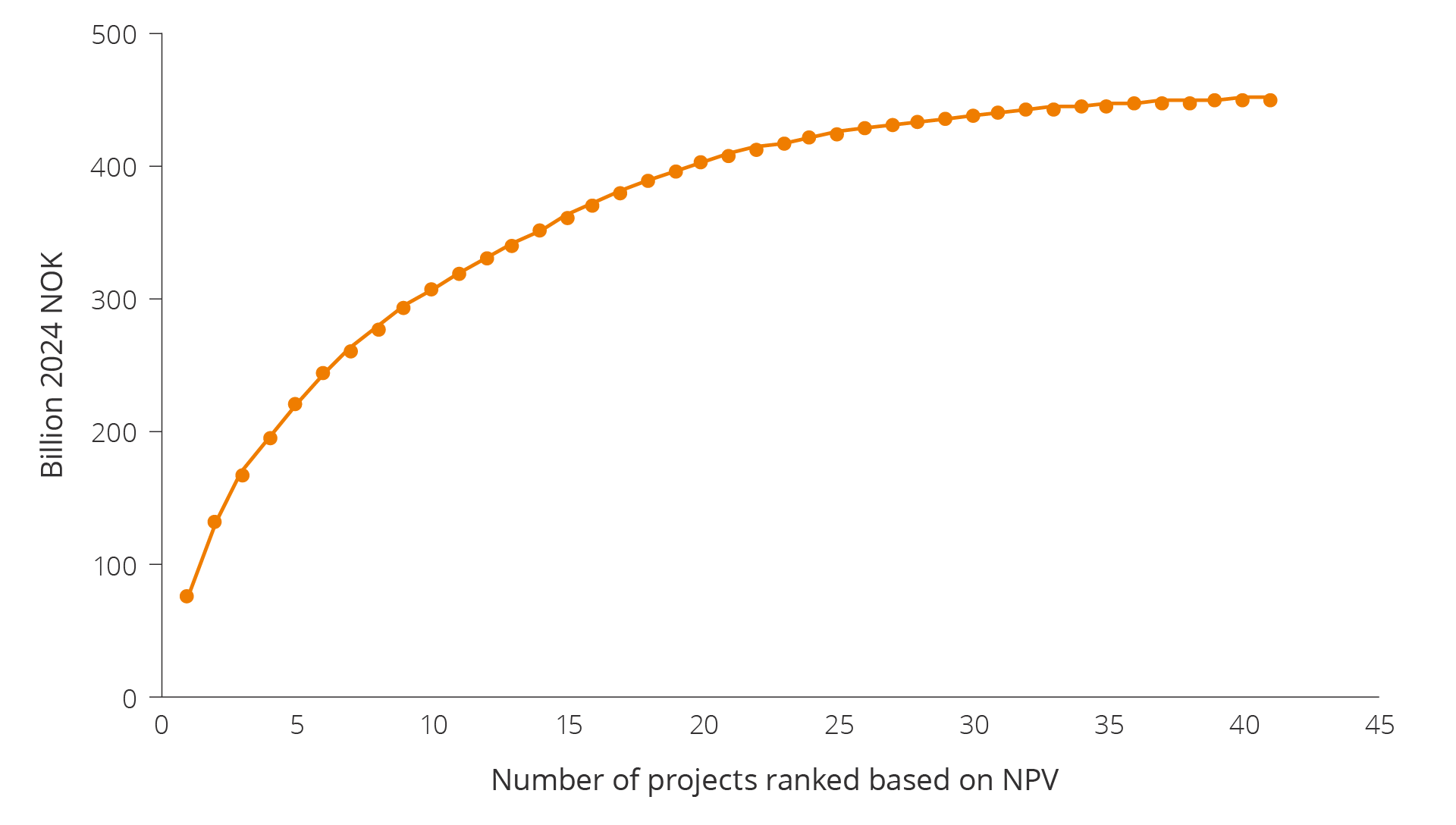

Market failure and improved recovery

The companies' required rate of return and absolute net present value requirements mean that fewer improved recovery projects prevail in the companies' project selection and decision-making processes(25). This means that socio-economically profitable projects are not implemented.

This was also emphasised by the Office of the Auditor General of Norway (the OAG) in their 2015 report, that showed that companies consistently have higher rates of return than the state. This indicates that fewer improved recovery projects are profitable when the companies' own required rates of return are applied.

According to the OAG, this, alongside the companies' limited access to capital, means that projects with a positive net present value with the companies' own required rates of return are not necessarily realised. Only the most commercially profitable projects (projects with high net present value) are realised, as the companies apply additional criteria before they accept a project. The OAG was concerned about a lack of focus on socio-economically profitable measures to increase production from mature fields.

New development wells

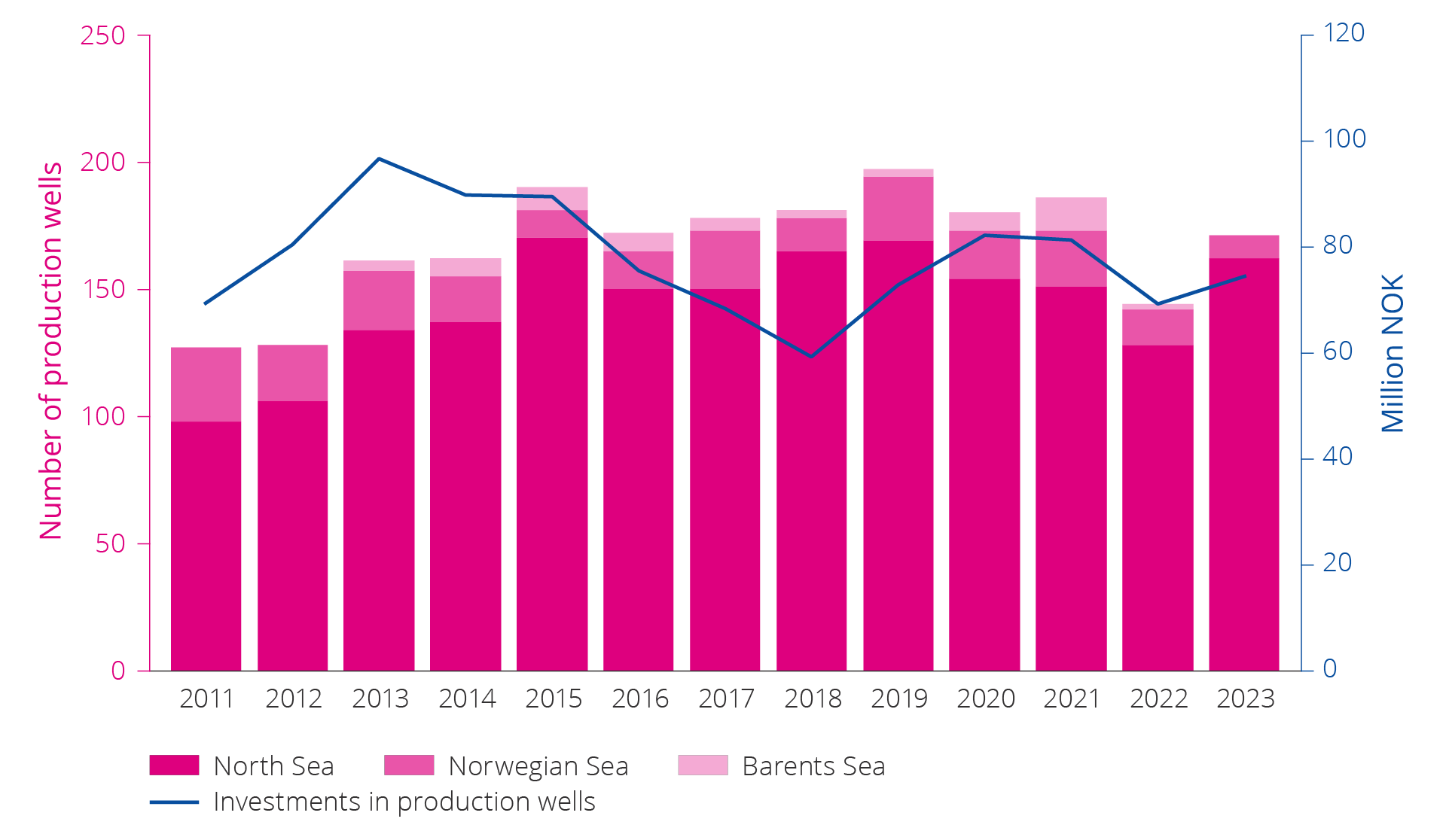

Measures to improve recovery are dominated by new wells, both in number and in volume. Drilling new development wells is entirely crucial to slow the decline in production, particularly for oil fields as illustrated in figure 5.10.

Figure 5.10 Number of development wells and investment in production drilling on the NCS over time from 2011–2023.

Low-pressure production

The pressure differential between the reservoir and the wellhead on the installation is what makes it possible to produce oil and gas. When petroleum is produced from a reservoir without injecting a corresponding quantity, the reservoir pressure will be reduced.

Gas fields do not normally utilise injection for pressure support. Declining reservoir pressure means that the wells will eventually produce at lower rates (volume per unit of time) as a result of the reduced pressure differential. One measure that can be implemented to maintain higher production rates is lowering wellhead pressure.

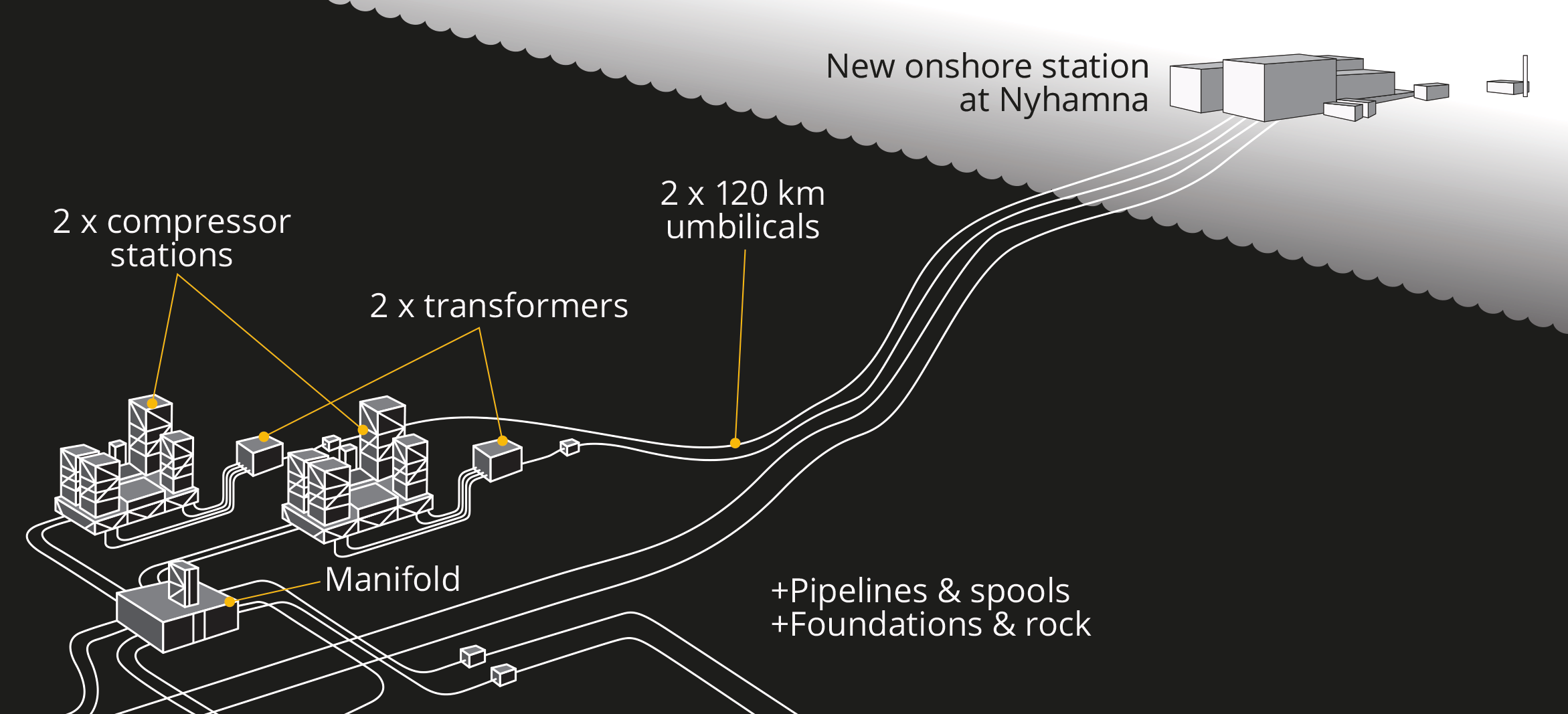

Lower wellhead pressure increases the production rate from the wells and ensures that a greater share of the resources can be recovered. This is achieved either by installing compressors between the wellheads and the process plant, or by lowering the receiving pressure at the installation/onshore facility. Åsgard and Ormen Lange are examples of fields that have, or are in the process of, installing seabed compression. Onshore compression for the Ormen Lange field started in 2019, and the field is now being further developed with subsea compression. The plan for development and operation was approved in 2022. Two compressor stations that handle rich gas will be installed on the seabed near the wellheads. This is expected to improve recovery by up to 30-50 billion scm of gas from Ormen Lange, which is expected to increase the field's recovery rate from 75 to 85 per cent; see figure 5.11.

If low-pressure production is implemented by reducing the receiving pressure at the installation/onshore facility, processing capacity will be affected. At this point, it may be necessary to modify the export compressors, in order to continue delivering gas that satisfies the required export pressure.

Figure 5.11 Ormen Lange subsea compression (adjusted according to illustration from Shell).

Phasing in discoveries to existing fields and infrastructure

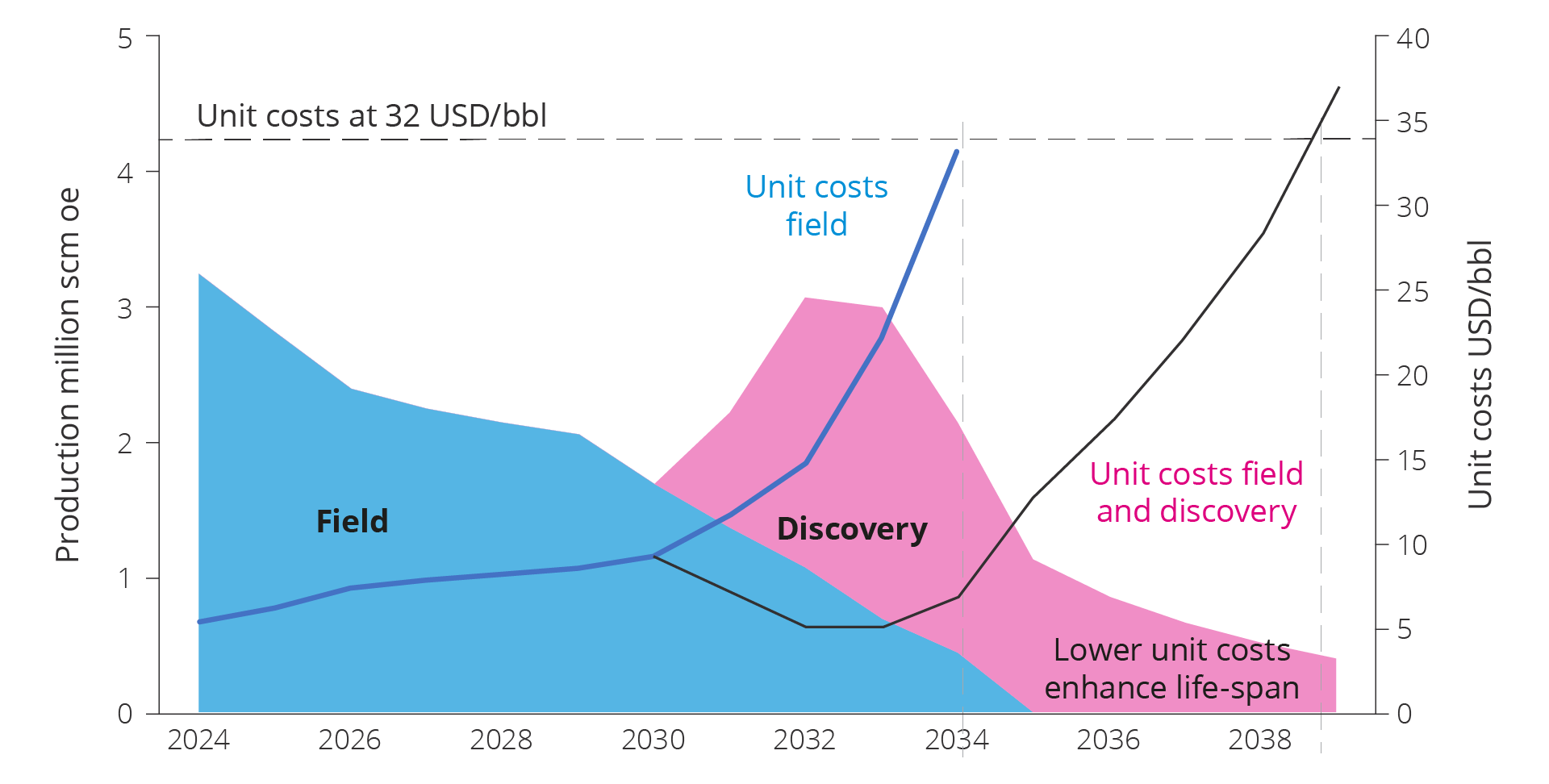

Phasing in discoveries to existing fields can help extend the lifetime of the host field and thereby ensure continued profitable production and improved recovery.

The example in figure 5.12 is from the NCS and shows that a new discovery helps keep unit costs down. This can contribute to an extended field lifetime and provide incentives for further exploration in the area.

Figure 5.12 Connecting new discoveries to existing fields and infrastructure.

Time-critical resources

Time is a critical factor for a tie-back to a producing field (host field) due to its limited lifetime as well as rising unit costs as the host field approaches shutdown. It is important that the phase-in takes place before the unit cost of the host becomes too high. For this reason, future development of discoveries is not only dependent on available capacity, but also capacity at low unit costs; see chapter 6, exploration creates substantial values.

Several of the phase-in projects are in addition complex, and low capacity in process and transport systems or competing alternatives can affect the solution selection. Different ownership structures can also make it challenging to find good solutions across fields, discoveries and infrastructure.

Unit costs and need for consolidation

Eventually, the access to resources from new discoveries will be insufficient to counteract production decline from the fields, and there will be a need for consolidation to avoid exceedingly high unit costs. Consolidation may result in decommissioning of certain installations and optimisation of remaining infrastructure utilisation.

The decommissioning of installations may also result in the loss of exploration opportunities or other projects aimed at increasing access to resources in an area. The value of these resources must be weighed against the cost of maintaining infrastructure with high unit costs. Area analyses indicate that the loss of resources and value as a result of decommissioning can be mitigated in areas with well-developed infrastructure, by re-directing resources to another host field. However, this is difficult to achieve in practice; see fact box on market failure in the phase-in of discoveries. Experience indicates that fields, discoveries and undiscovered resources must be viewed in context before such decisions are made, so that necessary studies for this are conducted in time.

Resources and challenges in discoveries

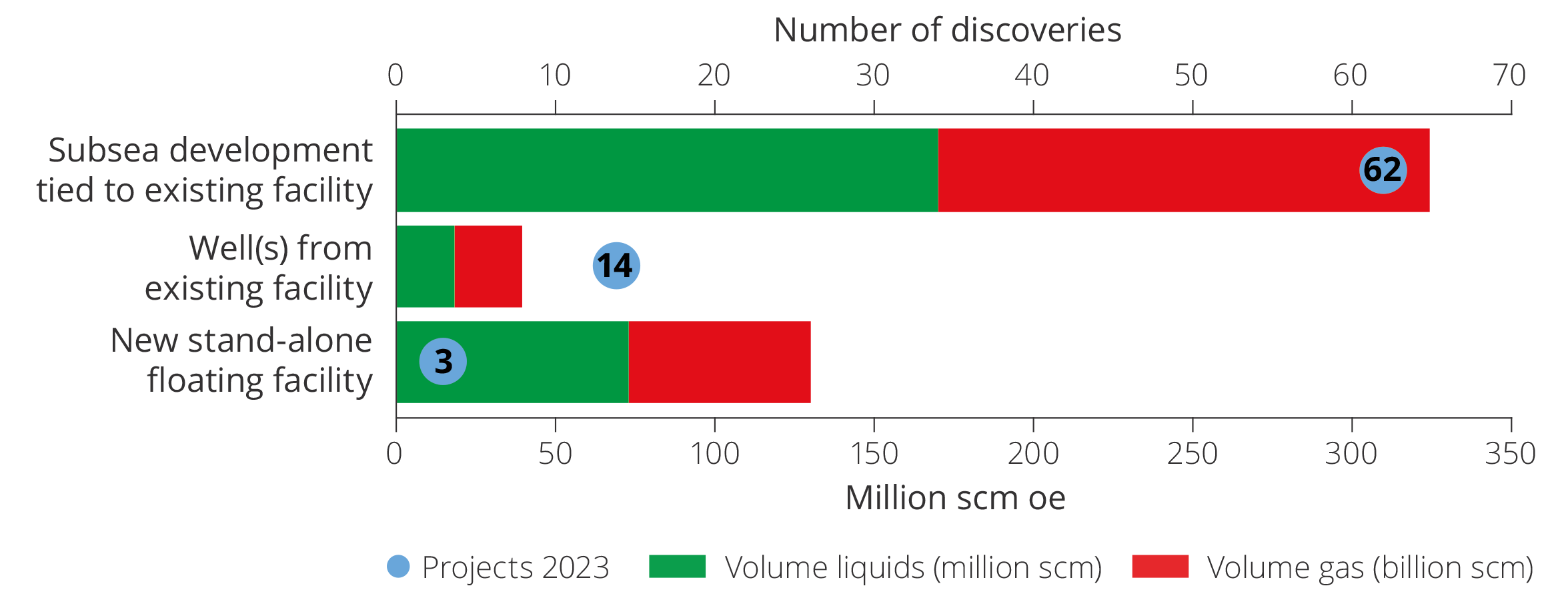

The production decline can be slowed if discoveries are developed and put on stream; see figure 5.13. At the end of 2023, there were 79 discoveries (see note in resource classes 4F, 5F, 7F in the Resource Accounts for 2023) on the NCS where no decision had yet been made to develop, but where the licensees are considering development.

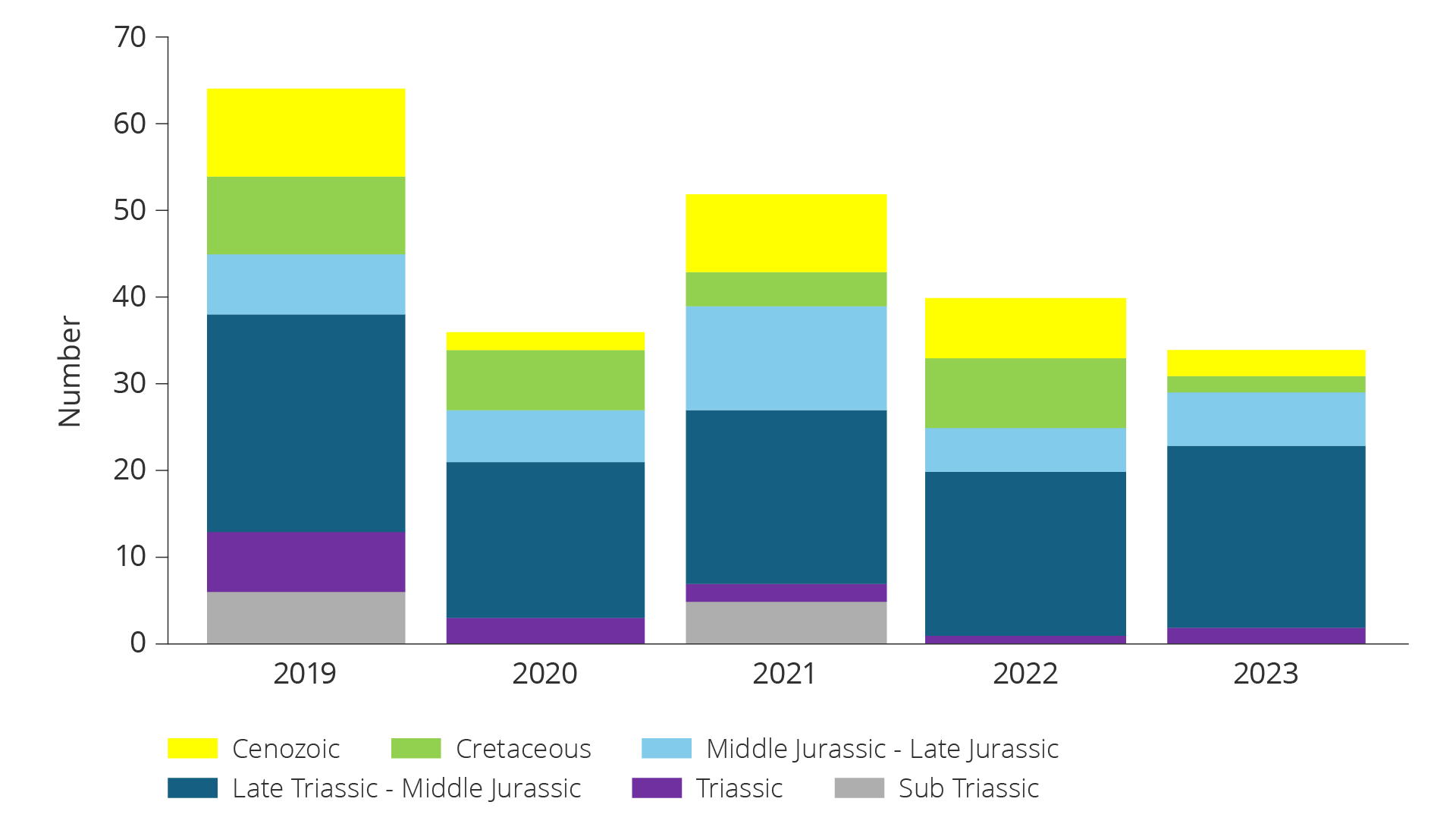

Resources in discoveries total 494 million scm oe, split between 261 million scm of liquids and 233 billion scm of gas. Together, the size of the resources in the 79 discoveries is on par with the original resources in the Åsgard field.