Background

THE WORLD NEEDS ENERGY

The world needs energy, which is why there will still be demand for oil and gas in the years to come. Norwegian oil and gas can continue to play a role in ensuring that Europe has secure and stable energy supply. Considerable investments will be needed in order to slow the declining production from current oil and gas fields.

In this chapter:

- Uncertain global landscape

- The world needs oil and gas

- The Norwegian continental shelf is competitive

- Need for considerable investments moving forward

- New industries on the shelf

The Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) has supplied Europe with oil and natural gas for more than 50 years. The efforts invested on the NCS have brought secure and stable energy to Europe, while simultaneously providing Norway with vast revenues. Norway is currently the largest producer of oil and gas in Europe.

Uncertain global landscape

The global population, as well as business and industry, need energy to function and to reach the UN's Sustainable Development Goals(1). Uninterrupted access to sufficient energy at acceptable prices is a prerequisite for sustainable economic progress and social welfare development. Procuring enough energy for a growing global population poses however a significant challenge.

With the exception of brief periods during economic crises, global energy consumption has increased year-on-year. Particularly rapid energy consumption spikes have been observed in important regions of the global economy during periods of high economic growth. Whereas developing countries are especially vulnerable in terms of underlying energy needs. Their growing populations need energy to meet basic needs and achieve their desire for a better life and higher standard of living.

Significant and rapid emission cuts, in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, will require an energy transition involving extensive changes in global energy supply. Among other things, this includes energy efficiency measures, more development of renewable energy alongside new low-emission solutions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS). The energy and climate challenges the world is facing will need a range of simultaneous solutions.

Coal, oil and gas dominate the current, complex global energy system. This dependence leads to substantial greenhouse gas emissions, which have serious and irreversible consequences.

These energy sources have consistently accounted for around 80 per cent of the overall energy supply. More prevalent use of new energy sources has made significant additional contributions to existing sources, a factor which has been crucial in addressing rising energy needs. Furthermore, there is still extensive use of traditional biomass, with the associated challenges this brings for many low-income countries.

It will be challenging to implement the necessary transition of global energy systems quickly and the pace is uncertain. An energy system that is consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement will however be entirely different from the system in place today. Renewable energy will be an important part of the solution, but as of today, it is difficult to predict which combination of technologies and solutions will prevail and succeed. Particularly when other societal considerations are also taken into account. The uncertainty surrounding future developments has therefore a direct impact on the need for the different energy sources.

Both commercial and political reasons have led various business sectors in the West to limit their investments in fossil energy, which to a lesser extent, are also being seen in other parts of the world. Many western countries have introduced measures to improve their energy security in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. At the same time, several major oil companies have tweaked their business strategies to reflect a more balanced split between oil and gas activities on one side and renewable energy on the other.

While European gas prices so far in 2024 remain far lower than the record prices in 2022 and the last half of 2021, prices are still high in a historical and global perspective. In Europe, the lapse of Russian gas deliveries has led to a significant increase in imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). LNG represents a link, both physically and in terms of price, between the gas markets in Asia, Europe and the US.

The global balance and competition in the LNG market is one of the most important drivers behind the evolution of European gas prices. Developing countries that import LNG are most vulnerable to the impact of high gas prices, but even in Europe, this is a challenging price level for households, businesses and energy-intensive industry.

The world needs oil and gas

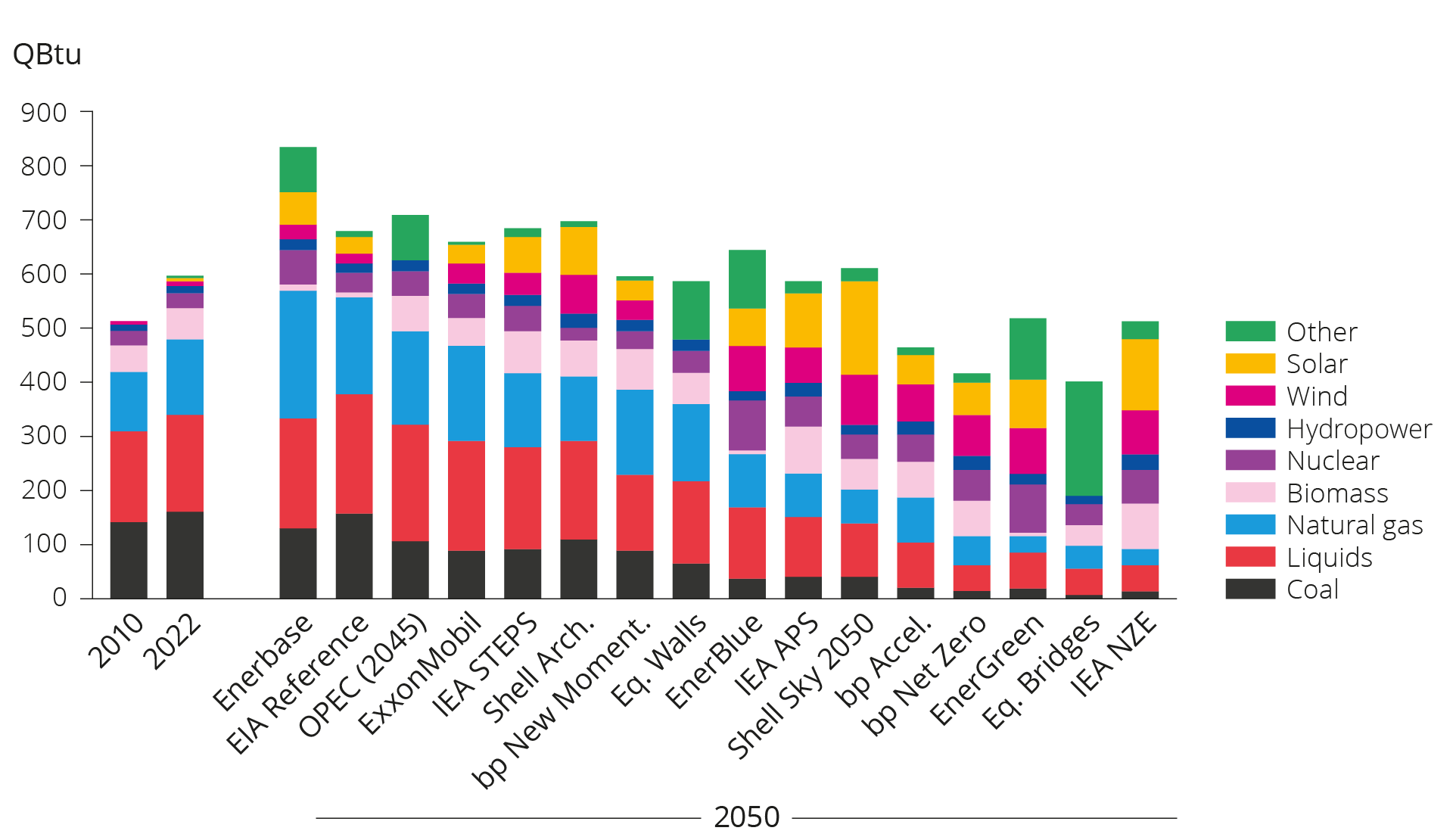

Oil and gas accounted for about 55 per cent of total global primary energy consumption in 2023(2). According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and other analyst communities, there will still be a need for oil and gas in 2050, see figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Global primary energy demand in 2050, different energy forecasts and scenarios. Source: Resources for the Future, 2024; British thermal units – Btu.

This figure was prepared by the US-based independent research foundation Resources for the Future (RFF)(3). Each year, RFF compares various selected long-term energy forecasts and scenarios in an effort to identify primary trends in global energy consumption and production. In most scenarios, global demand for primary energy will either grow modestly or decline toward 2050. This will be the case despite the substantial expected increase in global population. The main reason for this is a global economy that is becoming more energy efficient.

Six of the scenarios show increased demand for oil/liquids leading up to 2050, while demand for natural gas rises in eight, which is half of the scenarios. Consumption will remain high after 2050, despite a decline in demand for fossil energy. This will be the case even in normative scenarios where global warming is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

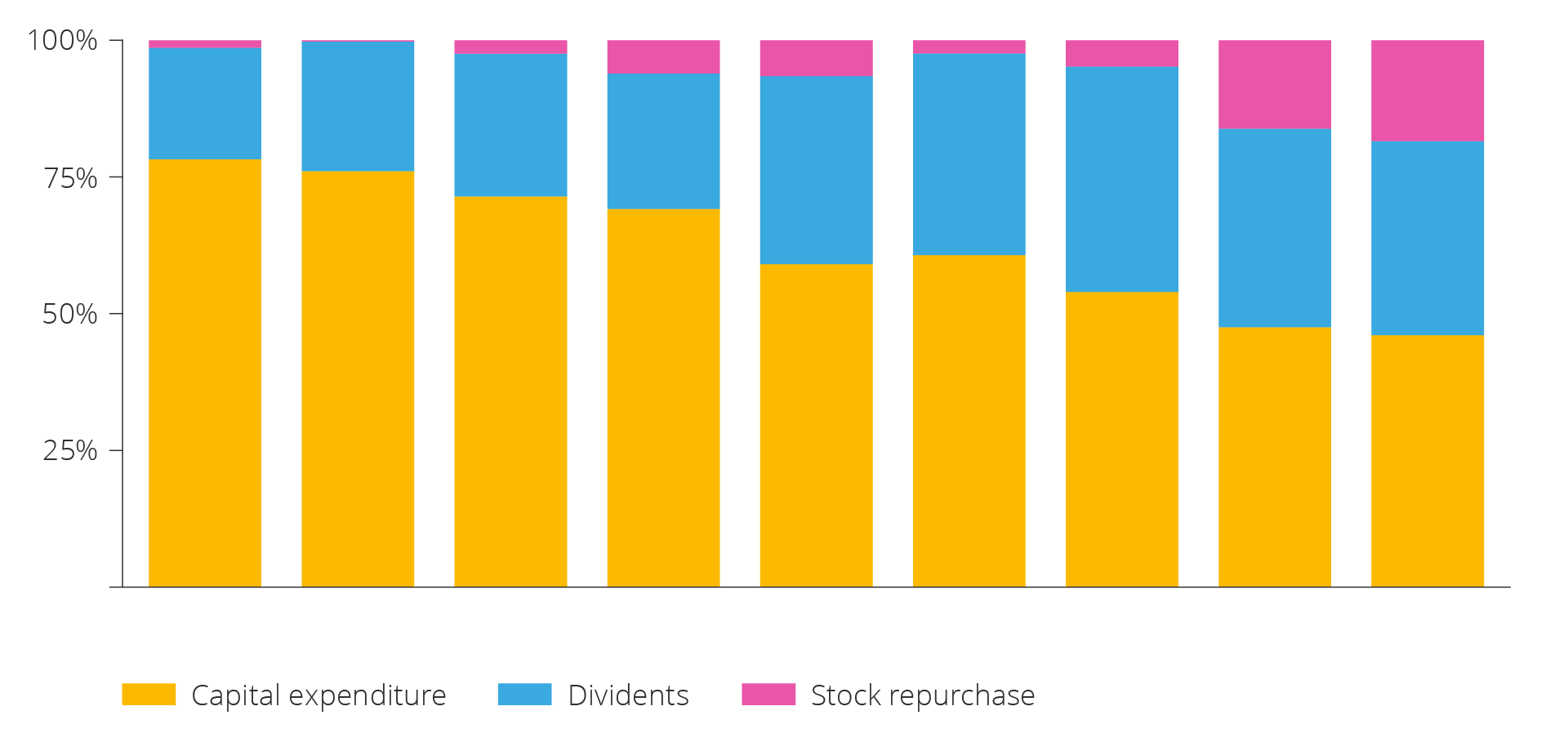

As production from current oil and gas fields is subject to natural decline, considerable investments in new capacity will be needed in order to meet future demand. In relative terms however, the industry(4) expends less capital on new investments than on dividend and share buybacks, see figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Expenditure on investments in exploration and recovery, dividend and share buybacks for the 30 largest oil and gas companies, 2015–2023 (Source: IEA 2024).

Companies will likely lean towards investing capital in oil and gas resources they find most profitable, which generally means oil and gas resources with low costs and low emissions per produced unit. These are often called 'advantaged' resources(5). The companies are therefore expected to seek out such advantaged resources, rather than investing in existing discoveries and fields challenged by high costs and emissions. Heavy oil and shale oil are examples of more challenged resources.

A study conducted by Wood Mackenzie(6) shows that there are few advantaged oil and gas resources available globally to meet future demand. Yet, these resources are plentiful on the NCS.

The Norwegian continental shelf is competitive

Nearly all oil and gas produced on the NCS is exported to Europe. This helps ensure a safe and stable energy supply for Europe.

The removal of Russian gas following the invasion of Ukraine laid bare the importance of stable gas deliveries from Norway to the rest of Europe. In 2022, Norway increased its gas exports by about 8 per cent or 9 billion scm (standard cubic metres). Deliveries from Norwegian fields have helped cover a higher share of Europe’s gas needs than before. The volume supplied by Norway now corresponds to about 30 per cent of the EU’s and UK's total gas consumption.

Without deliveries of these Norwegian resources, Europe would have a greater need to purchase LNG on the global market. This in return, would lead to a tighter global market, and would also have a greater impact on developing countries in Asia that need to import gas. Without deliveries from Norway, European gas and energy prices could be even higher.

Access to energy have increasingly become part of national security policies. Norwegian presence in the high north and Norway’s protection of critical societal functions such as gas infrastructure, will likely only become more important moving forward.

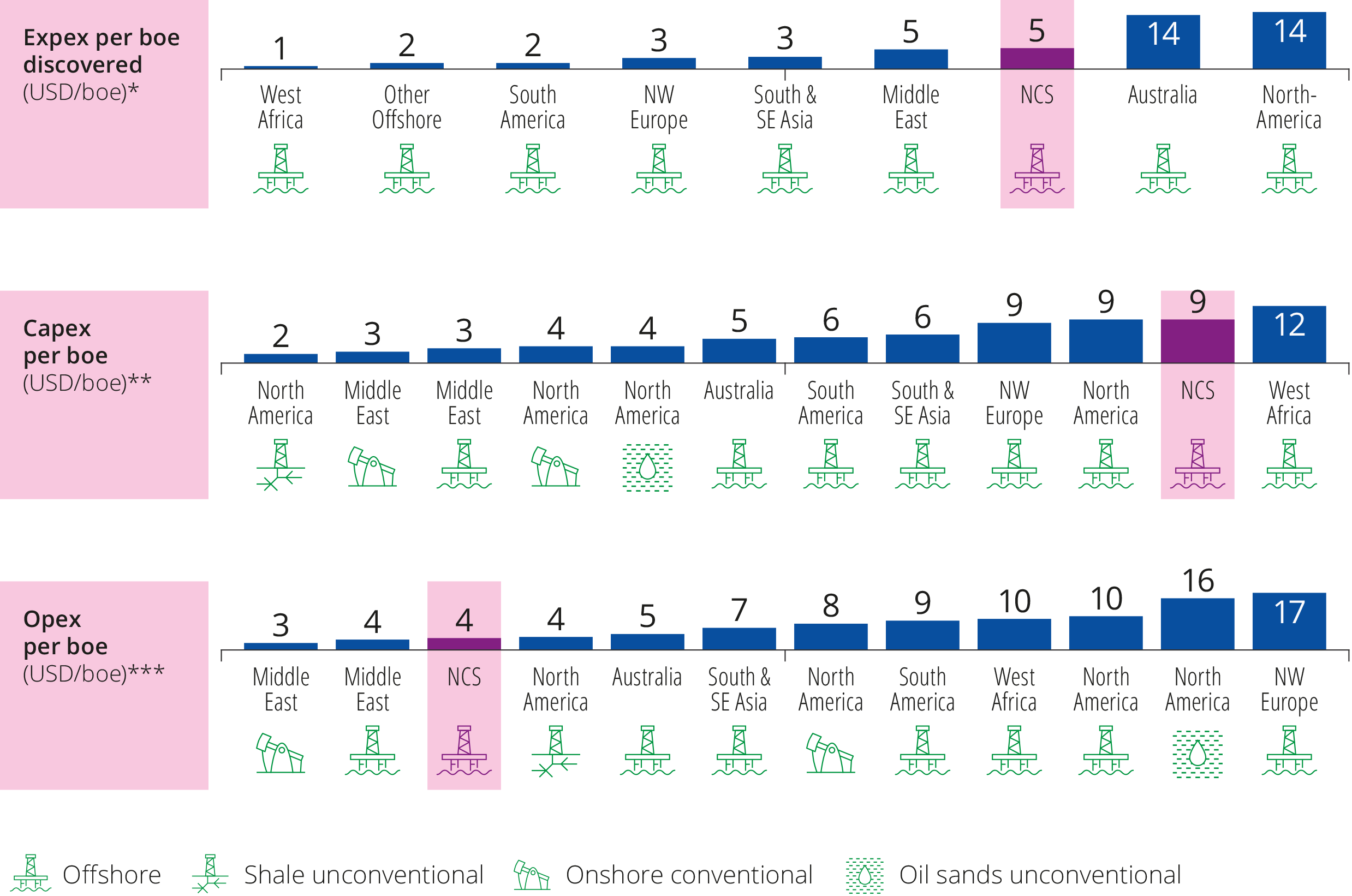

In spite of somewhat higher exploration and development costs compared with other petroleum provinces, the NCS is well-positioned to remain a competitive producer and exporter of oil and gas.

The relatively higher costs are caused in part by the fact that activities take place far out at sea and under challenging weather conditions. Substantial remaining resources, well-developed infrastructure, low operating expenses and stable framework conditions make the NCS an attractive investment opportunity, see figure 3.3(7).

Figure 3.3 Unit costs for exploration, development and operations on the Norwegian shelf compared with other petroleum provinces in 2021.

*Exploration expenses per barrel; offshore only. Only includes commercial discoveries where public information is available. Average of 2019 and 2020.

**Greenfield capital expenditures related to sanctioned oil and gas fields in current year. Volume-weighted average of 2019 and 2020.

***Operating expenses do not include transport costs and tax. Only includes opex associated with the production of hydrocarbons in addition to sales, general and administrative expenses (Source: OG21 2021).

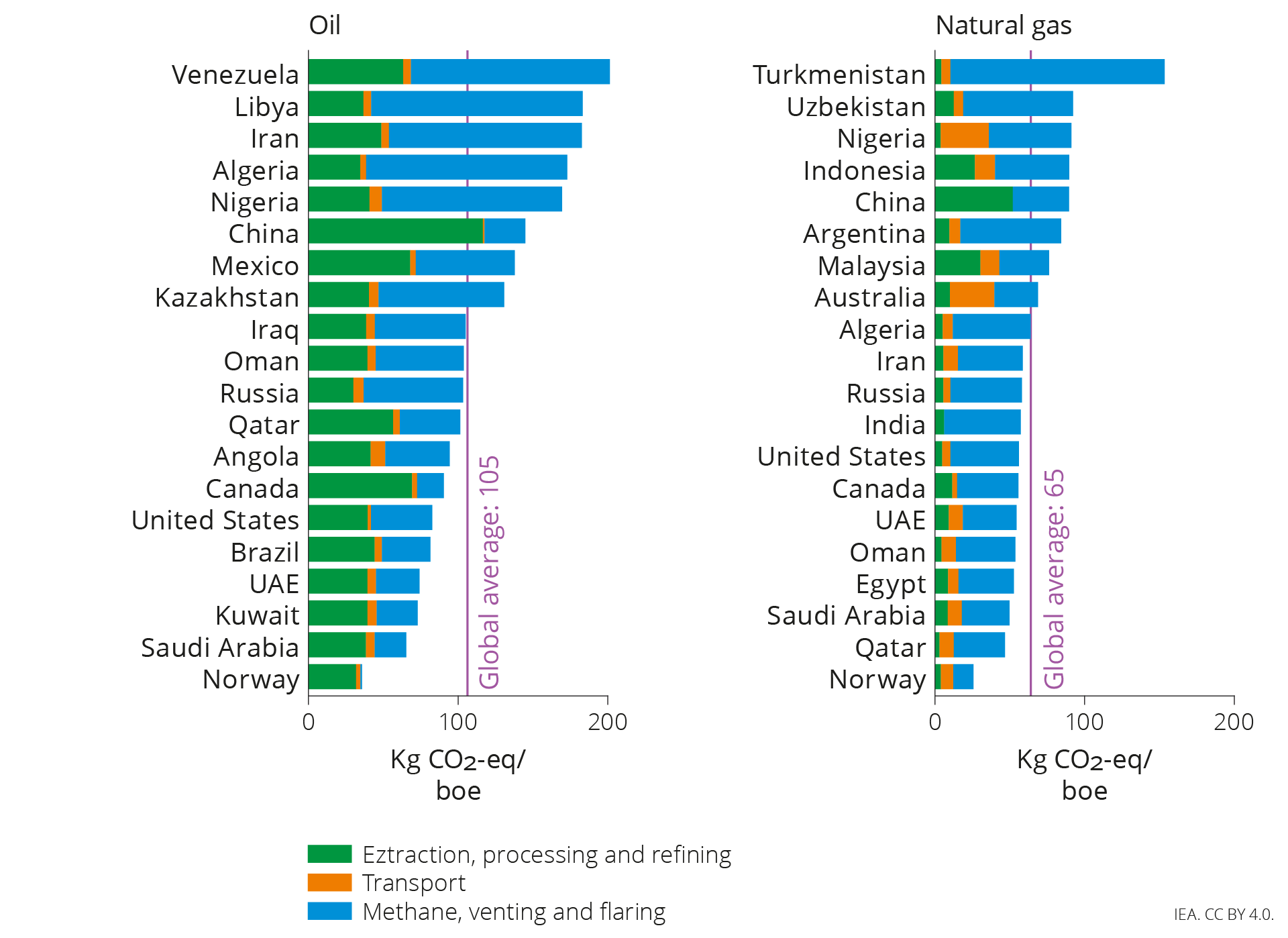

The NCS has very low greenhouse gas emissions per produced unit compared with other petroleum provinces, see figure 3.4(8).

Figure 3.4 Comparison of average emission intensity in kg CO2 equivalent/bbls of oil equivalent in 2022 for the largest oil and gas producers (Source: IEA 2023b).

Need for considerable investments moving forward

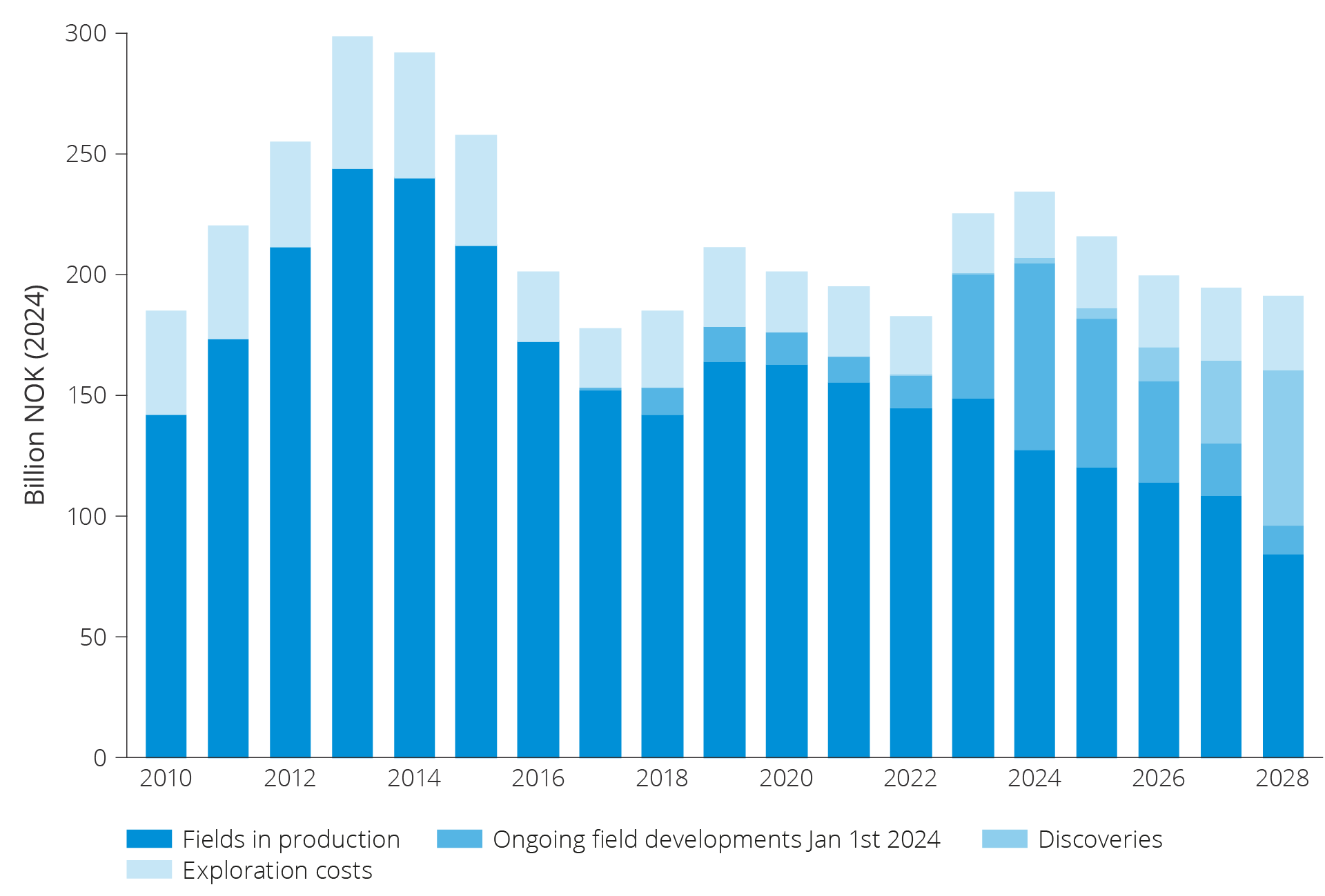

Petroleum investments increased sharply in 2023 after declining for three years straight, see figure 3.5. Investments in field developments were the main contributor to the increase, while the rise in exploration was more moderate.

The increase in 2023 must be viewed in context with high petroleum prices and the temporary changes in the petroleum tax rules that were implemented in connection with the oil price plunge in the spring of 2020. This ensured that plans for development and operation (PDOs) for as many as 13 new field developments were submitted in 2022. Several investment decisions were also made for further development of operating fields and improved recovery on existing fields.

The high number of field developments will contribute to stable activity levels moving forward. In a longer perspective, the decline in remaining resources is eventually expected to lead to lower investments in oil and gas production.

Figure 3.5 Historical petroleum investments and projections for future petroleum investments on the NCS.

Petroleum production on the NCS increased slightly in 2023 in relation to 2022, but has been on plateau more or less since 2021. It is below its highest level in 2010. At the same time, gas production declined somewhat from record-high levels in 2022. The production of petroleum has increased each year starting in 2020 (Figure 3.6) and is expected to increase further in 2024 and 2025. The Norwegian Offshore Directorate projects that the level in 2025 will be the highest since 2006.

Production from existing fields will presumably decline after 2025, and production and exports from the NCS will gradually start to fall if no action is taken.

Figure 3.6 Production history and forecasts by resource class (Resource Accounts as of 31 December 2023(7) RNB 2024).

In order to slow the decline in production, the companies will need to make more and larger discoveries and complete additional projects for improved recovery. The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's assessments indicate that In 2033, about one-half of total production will be from projects that have not been approved as of June 2024 (see resource classification below).

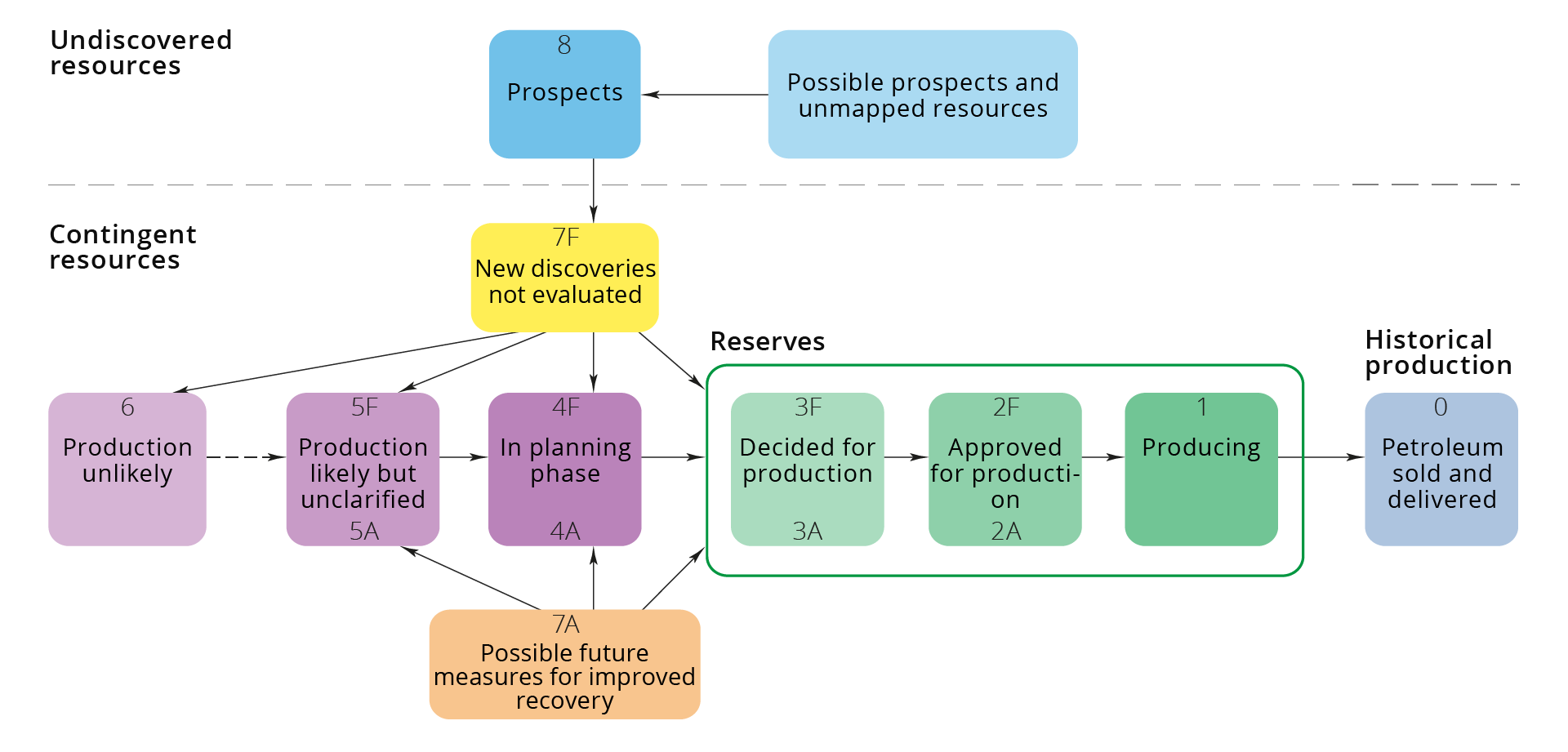

Resource classification

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource classification system is used for petroleum reserves and resources on the NCS (figure). This system is structured in such a way that the authorities receive the most uniform possible reporting from licensees as input to the Directorate's annual updating of the resource accounts.

"Resources" is a collective term for all oil and gas that can be recovered. They are classified in the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource classification system according to their level of maturity, with regard to how far they have come in the planning process from discovery to production.

Developed in 1996, the classification system was revised in 2001 and 2016. Changes in 2016 primarily involved language improvements, including new designations for certain resource classes. The classification relates to the total recoverable quantities of petroleum.

The system is divided into three classes: reserves, contingent resources and undiscovered resources. All recoverable petroleum quantities are called resources, and reserves are a special category of these. Reserves are the petroleum quantities covered by a production decision. Contingent resources cover both recoverable quantities which have been discovered but are not yet subject to a production decision, and projects to improve recovery from the fields.

The classification utilises the letters "F" (first) and "A" (additional) respectively to distinguish between the development of discoveries and deposits, and measures to improve recovery from a deposit. Undiscovered resources are petroleum quantities which could be proven through exploration and recovered. The quantities produced, sold and delivered form aggregate historical production(8).

Figure The Norwegian Offshore Directorate's resource classification system 2016.

New industries on the shelf

The need to reduce CO2 emissions means that multiple facilities will be needed to capture and store CO2 (CCS). CCS involves capturing CO2 from power generation and industry and transporting and storing it safely in geological formations deep underground. There are several suitable formations on the NCS.

The energy transition will also lead to an increased need for renewable energy, which is dependent on multiple minerals and metals. Some of which can be found on the NCS.

Seabed mineral extraction, CO2 storage and offshore wind may turn out to be profitable new industries on the NCS, presuming they are cost-effective and can compete with the alternatives. The costs can likely be reduced by leveraging synergies with the established value chains. At the same time, the established value chains can be strengthened through decarbonisation.

DownloadUpdated: 8/21/2024