Circle closed

Bjørn Rasen and Monica Larsen (photos)

Dag Bering’s father urged him to study manganese nodules in the Pacific when he first heard of them at the age of 10. Fifty years later, seabed minerals have finally been recovered from the NCS. Sadly, however, this key specialist is now retiring.

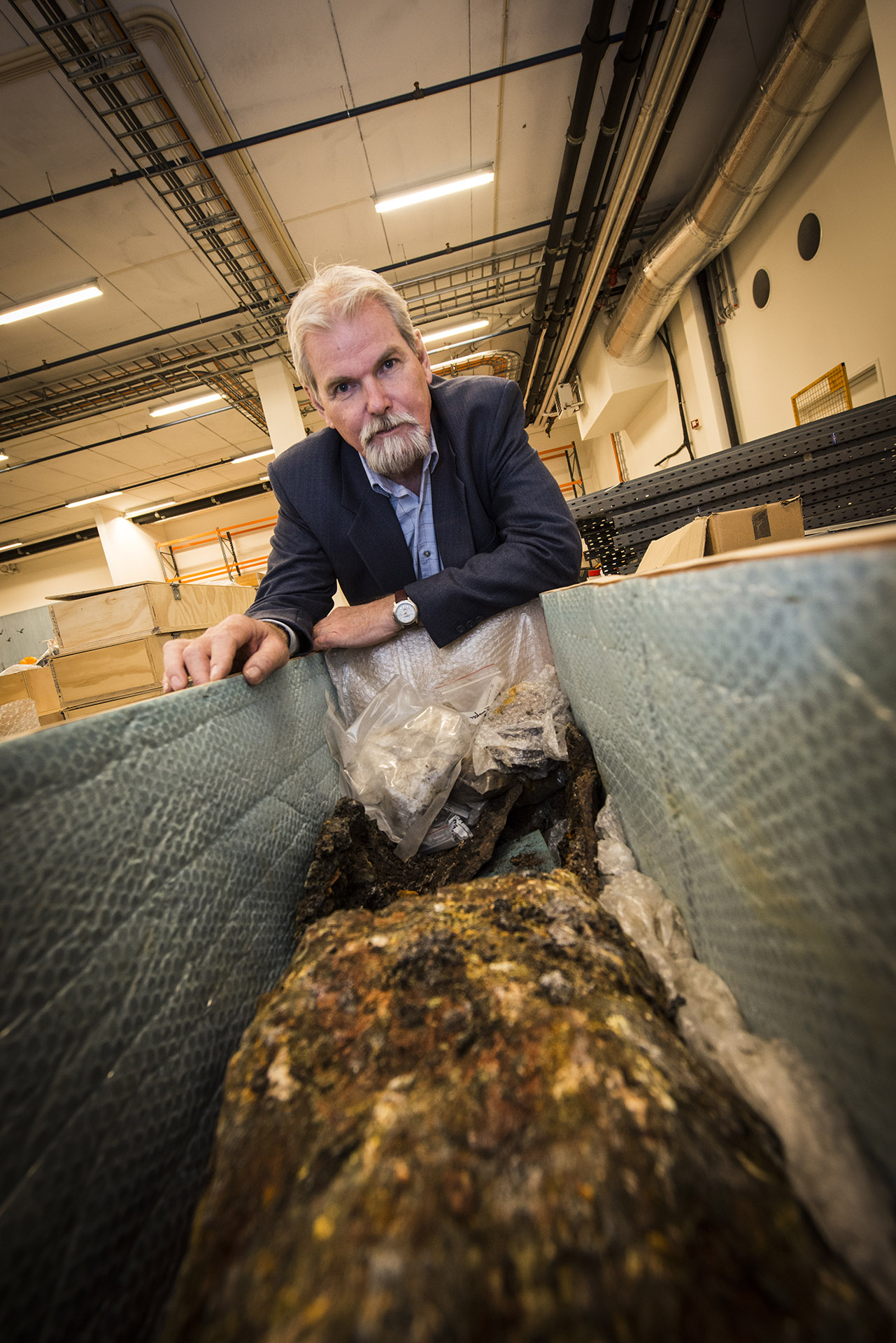

From the depths: It was a big moment for Dag Bering when the samples from some 3 000 metres beneath the Norwegian Sea were brought ashore in 2018.

The first thing Bering does when we meet is to emphasise that it will take a long time before any of these resources are recovered from the depths of NCS.

“A lot more mapping will be needed before then,” he says. “And we must study the impact of such production.”

He reports that a global hunt is under way on land for such metals – which are essential for the “green shift” – and that they are extracted under tough environmental conditions.

“Metals from new deposits on the seabed could be a better solution,” Bering says. “But we don’t know what such production would cost yet.

“What we do know is that certain metals in the seabed deposits are present in percentages of seven-eight per cent, compared with one per cent for mines in several African countries.”

The hunt today is for minerals containing valuable metals which the world needs, including rate earth elements (REEs). And some players have got off to an early start.

Bering reports that China currently controls about 90 per cent of the world’s REEs because the country has pursued a clear strategy here.

“If the Chinese wanted, they could reduce availability. That happened in 2010, when prices shot up. This led in turn to a big rise internationally in applications for prospecting licences.”

Expertise Dag Bering notes that the NPD’s 200 employees cannot match the oil companies for staff numbers, “but our expertise must be on a comparable level”.

Bank

Our meeting is in the NPD’s most international space – the rock store in what is now known as the Geobank. Bering has put in a substantial effort here ever since his arrival in 1990.

He has worked on resource data from the NCS, which play a key role in the NPD’s much-used fact pages on the web – which he helped to develop.

The rock store has cores from every one of the almost 6 500 wells drilled off Norway, for both exploration and production. Its cold room also holds oil samples from all the discoveries made.

In addition, the Geobank contains thousands of microfossils from the various wells. These holdings collective give the NPD a unique overview which benefits all the companies in their hunt for more oil and gas.

“We originally published geodata from the exploration wells – on paper,” Bering reports. “But that ceased in the early 1990s. The Norwegian Oil Industry Association complained a bit.”

Eventually, a work group got to grips with creating an internet version, and the rest is history. The fact pages are visited daily by hundreds of specialists.

The extent to which the companies have their own databases for such information is limited, and they rely wholly on the NPD to maintain an updated version.

Field

In his search to learn more, Bering has also been responsible for a number of field trips with the NPD’s geologists. These have often been fairly local, north and south of Stavanger, but occasionally range further afield.

Countries such as Denmark, Spain and Iceland offer rock formations on land which correspond with those found several thousand metres beneath the NCS.

“We’ve also taken non-geologists on such trips,” Bering says. “All our employees are involved in one way or another with the industry which produces petroleum from different formations. Understanding how this hangs together is important for doing a good job.”

The NPD must also be in step with the wider world, he notes. “We have to ensure that we do at least as good a job as the industry itself.

“We can’t challenge it to come up with better solutions for exploration, development and production if we’re not on the same level and don't possess the same expertise.

“Since there are 200 of us compared with several thousand in the companies, we can’t claim the same capacity – but our expertise must be on a comparable level.”

The alternative is failing to achieve efficient exploration of the NCS and optimal development solutions. But fortune favours the prepared mind, and he feels the NPD has been good at recruiting able personnel.

Thread

And expertise runs like a red thread through Bering’s life and career – ever since he learnt about the discovery of manganese nodules in the Pacific as a 10-year-old.

He joined the NPD after seven years as a researcher at the University of Bergen, and was given assignments as a geologist – starting with modelling the Gullfaks South field.

But his path took him more and more into research and development, and he has spent nine years as discipline coordinator for geology.

“Progress is what concerns me,” Bering says. “And to achieve that, we must establish various forms of collaboration with the outside world.”

He has been closely involved in that activity, with the forum for reservoir characterisation and reservoir engineering (Force) as the most outstanding example.

This body brings together government and industry, with the NPD as the secretariat, to share experience and develop methods for more efficient exploration and enhanced oil and gas recovery – and thereby to boost value creation from the NCS.

When its Profit predecessor terminated in 1993, Bering was among those charged with creating a new forum for scientists, government and industry to resolve common issues. Today, 23 years later, the Force seminar programme is fully booked – all the time.

Facilitates

Everyone must be involved, internally as well, says Bering, and has plenty of praise here for his long-standing employer.

“The NPD facilitates enhancement of both technical expertise and general understanding. That gives us a fine mix of specialists and all-rounders.”

It goes without saying that recruitment to the NPD and the industry in general is something which concerns him. This is a matter of capturing the interest of talented people early.

Bering has had various appointments in Norway’s education system to promote interest in the sciences. One of the most enjoyable was the Lego League contest for primary schools.

This got the children to develop various technological solutions with the aid of Lego bricks, in competition with other schools nationwide.

He hopes as many students as possible stay on the right track: “The nation needs geologists, in several sectors. I also think that youngsters who start out with this discipline in the oil industry will be able to stay in it until they retire.”

Cutting

He reads the newspaper reports that Norway’s Oil Age must end and that people like him will be redundant. Some universities are cutting back on petroleum research, which he thinks is “a pity”.

Many geologists are absent from these debates, and not even Bering feels a desire to go too far: “Geologists have a different time frame, and we know that the climate has changed throughout the ages. Nature isn’t stable.”

His realist side finds easy expression: “I believe we must accept that fossil energy will be required for a long time to come.”

Now that retirement beckons, Bering will have to watch the unfolding of the seabed mineral adventure from the sidelines. But one should never say never – although he says his current plans extend no further than maintaining house and holiday cabin.

Mineral hunt. The minerals now being sought include valuable metals, such as rare earth elements (REEs). The world needs these, says Dag Bering.

The magazine was produced prior to the corona crisis 2020.